-

Medical journals

- Career

Endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration of pancreatic cystic lesions – a single-centre experience, and comparison with resection histology

Authors: Koller T. 1; Piotrowicz A. 1; Tomáš M. 2; V. Gal 3

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 5th Department of Internal Medicine, Comenius University Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital Bratislava 1; Department of Surgical Oncology, SZU, National Institute of Oncology, Bratislava 2; Pathological Anatomy − DCP Bratislava, Unilabs Slovensko, s. r. o., Bratislava 3

Published in: Gastroent Hepatol 2021; 75(5): 381-389

Category: Original Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.48095/ccgh2021381Overview

Background: Pancreatic cystic lesions (PCLs) are being more frequently diagnosed and some have the potential for malignant transformation. The decision for performing EUS-FNA and indicating surgery remains challenging. Aims: To evaluate the feasibility and diagnostic yield of EUS-FNA, and in patients undergoing surgery to compare results of EUS-FNA with the resection histology. Methods: A retrospective observational study in patients undergoing EUS-FNA for PCLs. We assessed morphological risk features: solid component, a mural nodule >5 mm, dilated pancreatic duct >5 mm, lesion size >4 cm. The mucinous content was defined macroscopically by positive string test/thick mucin and/or by high CEA (>100 ng/ml) or low glucose (<2.8 mmol/l). Aspirated material was smeared and sent for cytology. Results: We included 30 patients, an M/F ratio of 20/10, with a median age of 66.5 (IQR 58–73) years. Seventeen patients had one or more risk features, 13 had none. The macroscopic evaluation of fluid was reported in 23 (76.6%) patients, it was positive in 14 (Group M) and negative in nine patients (Group N). The fluid analysis showed a presumed mucinous lesion in all patients in Group M, and four (44.4%) in Group N. Ten patients underwent surgery. Compared with resection histology, the presence of at least one risk feature had 100% sensitivity and 42.8% specificity for diagnosing high-grade neoplasia, the fluid analysis had 71.4% sensitivity and 66.6% specificity for a mucinous lesion, and cytological evaluation had 0% sensitivity and 66.6% specificity for high-grade neoplasia. Conclusion: Our study provides insight into the diagnostic complexity of PCLs. Our experience supports safe follow-up in patients without morphological risk features, and EUS-FNA indication in lesions with one or more risk features. Due to the high risk of malignancy, presumed mucinous lesions with a risk feature should be referred for surgery.

Keywords:

pancreatic cyst – pancreatic neoplasms – endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration – clinical decision-making

Introduction

In recent years, pancreatic cystic lesions (PCLs) are frequently diagnosed due to the widespread use of high-resolution imaging [1]. Some PCLs are benign, but some have a potential for malignant transformation. In distinguishing between them, imaging modalities are not sufficiently accurate [2]. Since pancreatic surgery carries a non-negligible risk of morbidity and mortality, more diagnostics are desirable before making decisions on further management. Due to its excellent spatial resolution, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was established as the imaging modality of choice [3]. Some morphological risk features like size, solid component, mural nodules, dilated pancreatic duct, or lesion growth, have been linked to a higher risk of malignancy. In addition, EUS fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has been proposed for helping to make a more accurate lesion characterisation. First, to differentiate between non-mucinous and mucinous lesions based on the macroscopic appearance of the content and fluid biomarkers. Second, the cytological or histological examination should help in further specifying the pathological diagnosis and identifying the grade of cell atypia. However, our understanding of the role of EUS - -FNA in PCLs is evolving and is still incomplete [4]. Some authors report excellent accuracy [5], some question the utility of EUS-FNA in providing any measurable clinical benefit [6]. Moreover, there are substantial differences among the published guidelines on the recommended indication of EUS-FNA. Japanese guidelines recommend performing EUS-FNA in low-risk lesions to confirm their benign character [7]. In contrast, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) recommend EUS-FNA in lesions with high-risk features to confirm the indication for surgery [8,9]. The European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines from 2017 recommend performing EUS-FNA when the expected result will change patients’ management, except for lesions <10 mm [3]. The European Study Group on Cystic Tumours in 2018 does not recommend EUS-FNA when there is a clear indication for surgery while stating that EUS-FNA increases the accuracy in differentiating non-mucinous from mucinous, and malignant from benign lesions [10]. Therefore, in clinical practice, the decision about when to perform the EUS-FNA in PCLs remains challenging. Finally, the decision for performing surgery is always based on balancing individual aptitude and acceptance of the risk of surgery, with the risk of malignant transformation [11].

We aimed to evaluate the feasibility and diagnostic yield of EUS-FNA in pancreatic cystic lesions in our healthcare setting. Also, in patients undergoing surgery to compare the presumed diagnosis of the lesion with the histological diagnosis after surgical resection.

Patients and methods

We carried out a retrospective observational study including consecutive patients undergoing EUS-FNA for PCLs in a single centre over three years. Patients were referred to us by gastroenterologists or surgeons. We recorded basic demographics, the presence of symptoms attributed to the lesion, morphological characteristics of the lesion such as location and lesion size. We systematically looked for risk features associated with a higher risk of malignancy: a solid component, mural nodule larger than 5 mm, main pancreatic duct wider than 5 mm, and lesion size larger than 4 cm. All EUS‑FNA procedures were performed as first EUS examinations and data on lesion growth were not available. CT and MRI reports were not available in all patients. The EUS report did not systematically include the statement on the communication with the pancreatic duct, so the study did not aim to differentiate the subtype of a mucinous lesion (cystadenoma or intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN)). FNA procedure was carried out by a single operator using a linear probe and a fine needle with 25G or 22G caliber (Expect or Acquire, Boston Scientific). Before the puncture, the stylet was left in the needle to avoid contamination with cells and mucus of the gastrointestinal mucosa. After puncturing the lesion we removed the stylet and with the mounted syringe we applied 5 ml of suction. Aspirated material was observed and processed.

Macroscopic examination of the aspirate

According to the initial macroscopic aspect of the cyst fluid, lesions were divided into three groups. Group M included lesions with the mucinous aspect defined by thick mucus or positive string test. It was positive when the fluid drop placed between the thumb and index finger and stretched formed a string longer than 3.5 mm. Group N included lesions with a liquid having a negative string test. Group UN included patients with non-feasible or unavailable macroscopic fluid evaluation.

Biochemical fluid examination

When enough fluid was obtained, we sent it for biochemical examination of the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), amylase (AMS), and glucose. Although most guidelines recommend the threshold for CEA >192 ng/ml, our laboratory uses the threshold >100 ng/ml. The mucinous content was defined by macroscopic mucinous aspect (thick mucus or string test) and/or cystic fluid with high CEA (>100 ng/ml) or low glucose (<2.8 mmol/l). Non-mucinous content was defined by negative string test/no thick mucus and negative fluid markers (CEA<100 ug/l, glucose >2.8 mmol/l) [4,12]. Cysts with non-mucinous content and high amylase content (>250 UI or >4.1 ukat/l) were classified as pseudocysts. Cysts with non-mucinous content with typical cuboid epithelial cells were classified as serous. Lesions with unavailable string tests and fluid markers were classified as of unknown origin.

Cytological examination

Solid or liquid needle content was primarily extracted into slides, immediately smeared, air-dried, and sent for cytological examination. Slides were fixed in isopropyl alcohol and stained according to Giemsa. Cytology evaluation was performed by a single pathologist (VG). Cell atypia was classified according to the Papanicolau Society of Cytopathology (I–VI).

Surgery

In patients undergoing a surgical procedure, we recorded the time-delay between the EUS procedure and surgery, the type of surgical procedure, and histological diagnosis of the resected specimen from the local pathology. The final diagnosis was compared with a presumed EUS‑FNA diagnosis in 10 patients.

Follow-up

The survival status of patients was verified from the national registry of inhabitants, and we recorded the time from the EUS procedure and death or date of registry check (12th July 2021) in days.

Ethical considerations

This was an observational retrospective study with no additional study intervention outside of the routine EUS-FNA. All patients have signed an informed consent form before the procedure. Data acquisition has been approved by the local ethics committee.

Statistical analysis

Results of numerical parameters are displayed as medians and interquartile ranges, proportions as numbers and percentages. For comparing numerical data, we used the Mann-Whitney test, for proportions we used the chi-square test.

Results

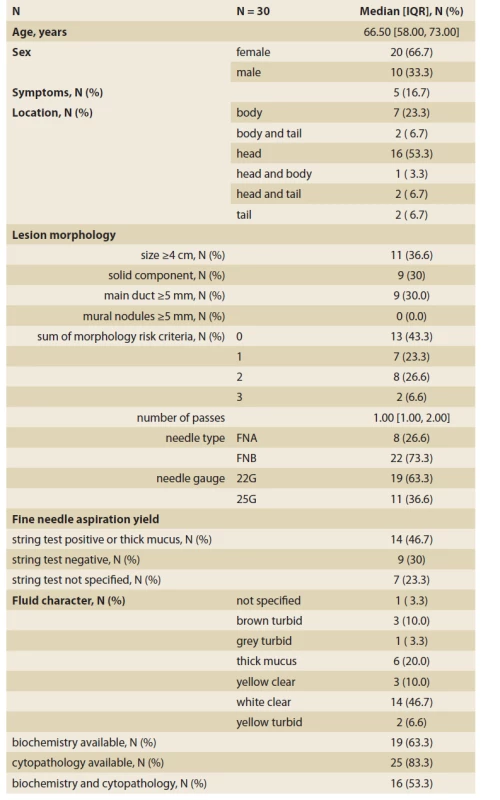

We retrospectively identified 30 patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria: 20 females and 10 males with a median age of 66.5 (IQR 58–73) years. Nineteen lesions were in the head of the pancreas, five lesions were symptomatic. The macroscopical evaluation of the aspirated fluid was informative in 23 (76.6%) patients and the remaining seven patients did not have data for unspecified reasons. EUS-FNA yielded sufficient material for cytological examination in 25 (83.3%) patients, biochemical analysis in 19 (63.3%) patients, and both in 16 (53.3%) patients. Summary statistics with more details of the patient and lesion characteristics are displayed in Tab. 1.

1. Summary characteristics of patients and pancreatic cystic lesions undergoing fine-needle aspiration.

Tab. 1. Sumárna charakteristika pacientov a pankreatických cystických lézií odoslaných na tenkoihlovú aspiráciu.

Morphological risk signs

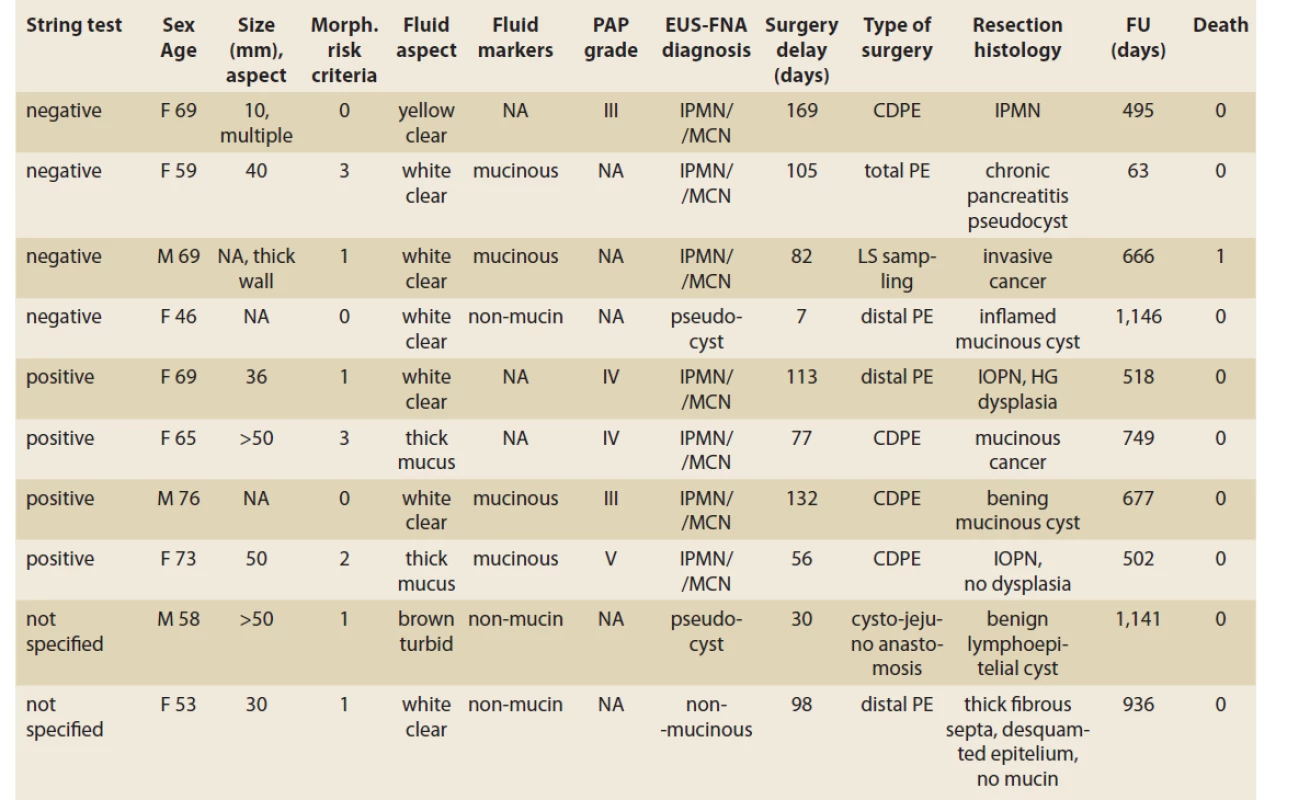

Morphological risk features were absent in 13 patients, seven patients had one, eight patients two, and two patients had three risk features. Among the 10 resected patients, three did not have any morphological risk signs. In two of three, the fluid analysis suggested a mucinous and one a non-mucinous content. Resection histology showed benign mucinous lesions in all three patients, two mucinous cystadenomas, and one IPMN (Scheme 1). The remaining seven patients had one or more risk signs. In five of seven patients, the fluid analysis suggested a mucinous and in two a non-mucinous content. Resection histology in five patients with suggested mucinous content showed advanced neoplasia in three patients (two carcinomas, one intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasia (IOPN) with HG dysplasia), one IOPN without dysplasia, and one pseudocyst. In two patients with the suggested non-mucinous content, one was a lymphoepithelial cyst and one a serous cyst (Scheme 1).

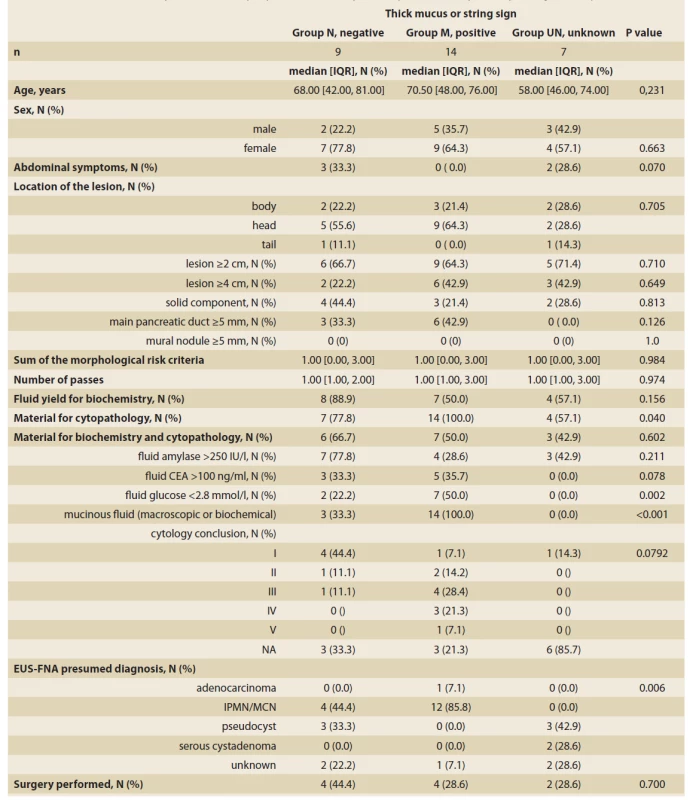

Cystic fluid analysis

In nine patients with a macroscopic non-mucinous aspect of the fluid (Group N), the biochemical analysis was feasible in eight (88.9%). Although the fluid aspect appeared macroscopically non-mucinous, the mucinous content was concluded in four of these nine patients. In three patients it was due to biochemical analysis (high CEA and/or low glucose) and in one due to cytological confirmation of mucin and mucin-producing epithelial cells. In Group N, the cytological evaluation was non-diagnostic or unavailable in seven of nine patients. In the remaining two patients it concluded a benign condition (PAP II) in one patient and some atypia (PAP III) in another. In Group N, four of nine (44.4%) patients underwent surgery. Resection specimen histology showed cancer in one patient (mucinous content with thick wall, EUS-FNA PAP I), a mucinous lesion without dysplasia in two patients (one with mucinous content EUS-FNA PAP III, one presumed pseudocyst), and a pseudocyst in one patient (mucinous content). More details are displayed in Tab. 2, 3.

2. Summary statistics and comparison of groups according to the macroscopic aspect of aspirated cystic fluid.

Tab. 2. Sumárna štatistika a porovnanie skupín podľa makroskopického posúdenia aspirátu cystickej tekutiny.

3. A comparison of EUS morphology, EUS-FNA fluid aspect and a presumed diagnosis of PCLs with surgical resection histology.

Tab. 3. Porovnanie EUS nálezu, aspektu aspirovanej tekutiny a predpokladanej diagnózy PCL s histologickým nálezom po resekcii.

CDPE – cephalic duodenopancreatectomy, PE – pancreatectomy, IPMN – intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia, MCN – mucinous cystadenoma, IOPN – intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasm, NA – not available, FU – follow-up, PAP – Papanicolau Society of Cytopathology grade, HG – high-grade, PCL – pancreatic cystic lesion In 14 patients with a macroscopic mucinous aspect of the fluid (Group M), the biochemical analysis was feasible in seven patients (50%). The mucinous content was concluded in all 14 patients. In six we observed thick mucin, in seven patients due to biochemical analysis and in one only due to positive string test. In Group M, the cytological evaluation was non-diagnostic or unavailable in four of 14 patients, atypical (PAP III) in four patients, benign neoplastic (PAP IV) in three patients, and neoplastic suspicious (PAP V) in one. In this group, four of 14 (28.6%) patients underwent surgery. Resection histology showed IOPN in two patients. The first patient had EUS-FNA PAP IV and the final histology showed IOPN with high-grade dysplasia. The second patient had EUS-FNA PAP V and the histology concluded IOPN with no dysplasia. In the remaining two patients, resection histology showed mucinous cancer in one (thick mucus, EUS-FNA PAP IV), and a benign mucinous cyst in another (EUS-FNA PAP II). More details are displayed in Tab. 2, 3.

In seven patients with no data on the initial macroscopic evaluation (Group UN), the biochemical analysis was feasible in four of seven patients. In all four patients, the biochemistry was compatible with a non-mucinous content. In the remaining three patients, there was no available diagnostic clue. In Group UN, the cytological evaluation was non-diagnostic in all seven patients. In this group, surgery was performed on two of seven patients (28.5%), both with a non-mucinous content. Resection histology showed a benign lymphoepithelial cyst [13] and a lesion with thick fibrous septa, no mucin production, and completely desquamated epithelial cell lining suggesting a serous cyst [14]. More details are displayed in Tab. 2, 3.

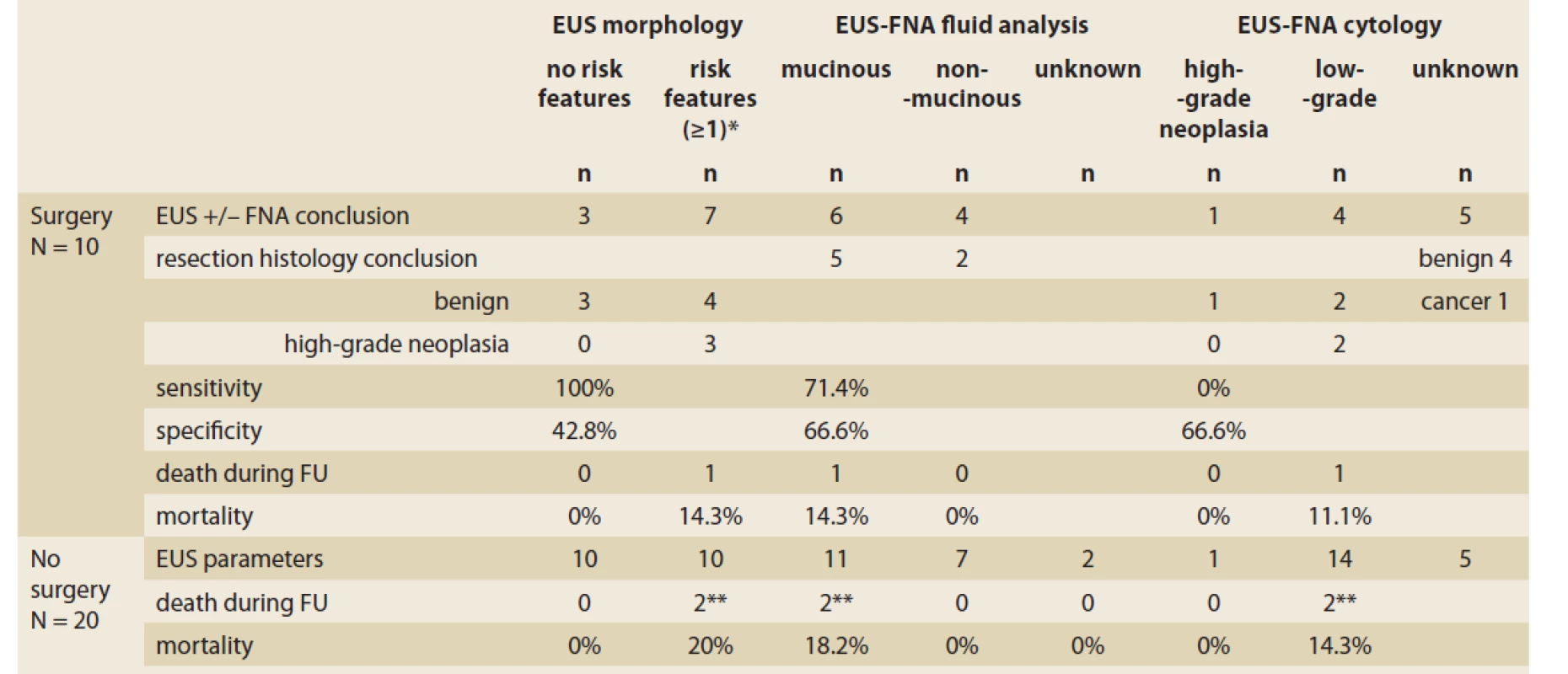

Diagnostic accuracy

In resected patients, we compared the resection histology with EUS-FNA and evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of EUS morphological risk features in the prediction of high-grade neoplasia, EUS-FNA fluid analysis in the prediction of mucinous lesions, and EUS-FNA cytology in the prediction of high-grade neoplasia. The morphological risk features had 100% sensitivity and 42.8% specificity for diagnosing high-grade neoplasia. EUS-FNA fluid content analysis had 71.4% sensitivity and 66.6% specificity for diagnosing a mucinous lesion. Dysplasia had 0% sensitivity and 66.6% specificity for confirming high-grade neoplasia. Details of the comparisons between EUS-FNA and resection histology are displayed in Tab. 4 and Scheme 1.

4. Diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA compared with resection histology and outcome in 10 patients with pancreatic cystic lesions.

Tab. 4. Diagnostická presnosť EUS-FNA v porovnaní s resekčnou histológiou a prognózou u 10 pacientov s pankreatickou cystickou léziou.

* main duct dilation > 5 mm, solid component, size > 4 cm, mural nodule > 5 mm

**1 patient with coincidence with solid lesion in the tailScheme 1. The flowchart of patients undergoing EUS-FNA for pancreatic cystic lesions and resection according to the initial morphological features.

Schéma 1. Schéma všetkých pacientov po endosonografickej tenkoihlovej aspirácii cystickej lézie pankreasu a resekcii podľa vstupných morfologických znakov.

MCN – mucinous cystadenoma, IPMN – intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia, NA – not available, PAP – Papanicolau Society of Cytopathology Grade, IOPN – intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasia, HG – high-grade.

MCN – mucinózny cystadenóm, IPMN – intraduktálna papilárna mucinózna neoplázia, NA – nie je k dispozícii, PAP – Papanicolauova spoločnosť pre cytopatológiu, IOPN – intraduktálna onkocytová papilárna neoplázia, HG – vysokokvalitný.Discussion

In our study, we explored the yield of EUS and EUS-FNA for diagnosing pancreatic cystic lesions. The study has several limitations. First, a low number of resected patients did not provide sufficient statistical power to draw firm conclusions. Second, indications for EUS-FNA were loosely defined and were left to the expertise of the referring gastroenterologists and surgeons. For example, some referring physicians and/or patients had an explicit desire for EUS-FNA for reassurance. Third, indications for surgery were not entirely based on the EUS and FNA findings, but also patients’ overall functional status, their attitude towards surgery, and agreement with the operating surgeons. Therefore, not all patients in whom EUS-FNA findings suggested the need for surgery were operated on. This might have skewed the calculated diagnostic accuracy. Fourth, our study is limited by the expertise and learning curve of our centre, and the involved biochemical and pathological laboratories. Fifth, this report is focused on the yield of EUS and EUS-FNA. Since detailed reports from MRI and CT imaging were not available in all patients, findings from other imaging methods were not considered. Also, a mention of the communication of the lesion with the pancreatic duct was not systematically reported. However, based on our observations few lessons can be learned.

EUS morphology could be evaluated in all patients and showed at least one risk sign in 17 of 30 patients (56.7%). The absence of a risk feature could accurately exclude high-risk neoplasia. However, all three patients had lesions with malignant potential (Scheme 1), so these lesions should be followed. Seven of 10 resected patients had a risk feature. Having a risk feature identified all three patients with high-grade neoplasia. Of the remaining four patients, three had a lesion without malignant potential. Hence, by sending all patients with risk features to surgery, three patients would undergo unnecessary resection. This highlights the necessity of EUS-FNA and is following ASGE and AGA guidelines [8,9] which recommend performing EUS-FNA in lesions with risk features to select patients who do not need resection.

Macroscopic and biochemical evaluation of the fluid was feasible in more than three-quarters of patients, biochemical analysis in two-thirds. Of the resected patients, mucinous content of the lesion was suggested by macroscopic and biochemical analysis in six of 10 patients, five of whom had one or more risk features. In four of these five patients, resection histology showed advanced neoplasia or IOPN with malignant potential. These findings support the recommendation that all lesions with risk features and mucinous content are potentially high-risk and should be considered for surgery.

The most disappointing results of our study came from the cytological examination. The specificity was lower than reported by the major studies [10], the sensitivity was very low. Since technical aspects of the procedure play an important role, there are conflicting reports on the diagnostic sensitivity of the cytological examination [4]. The epithelial cells of PCLs reside in the cystic wall and only a few are in the cyst fluid. Hence, the guidelines recommend complete removal of the cystic fluid and aspiration of the cystic wall. However, this is not feasible in all lesions due to thick mucinous content or intra-cystic debris. Also, after cystic fluid evacuation, isoechogenic cystic walls may become difficult to target. In our study, the lack of thorough wall aspiration could have been the reason for very low sensitivity compared with other studies. To overcome this limitation, several other modalities complementing EUS-FNA have been studied. Through the needle biopsy forceps were reported to have a higher yield for cytological evaluation, but its clinical utility is still questionable [15]. Mutations in the DNA of the cells aspirated from the cystic lesion have been associated with neoplasia or advanced neoplasia. Studies have shown good added value of these markers in diagnosing the dignity of PCLs. Currently, there is hope that next-generation sequencing will become the test of choice for a more accurate diagnosis of neoplasia in PCLs [16].

We admit to having some room for improvement in evaluating PCLs. Every EUS and EUS-FNA report should systematically specify the presence (or absence) of communication with the pancreatic ductal system, a precise macroscopic aspect of the fluid with string test or describe a thick mucinous content and the maximum size of all lesions. Finally, we should aim to evacuate the entire fluid content with subsequent FNA sampling of the cystic wall to provide more material for cytological evaluation.

Interestingly, two of the resected lesions were IOPNs. These rare lesions resemble IPMNs and have been recently characterised in a systematic review [17]. IOPNs were described as large, located mostly in the pancreatic head, and were asymptomatic. Most of the lesions were classified as carcinoma in situ or minimally invasive carcinoma. Overall, the prognosis was better than that of other IPMNs but surgical resection is recommended. Recurrence after surgery has been rarely reported. Our two patients with IOPN perfectly fit into the described picture, with lesion size 36 and 50 mm, mucinous fluid, advanced cytology grading (PAP IV, V), and high-grade dysplasia in one of the resected specimens.

In conclusion, our study provides a realistic, but limited insight into the diagnostic complexity in the management of PCLs. Our experience cannot draw any conclusion on the minimum lesion size indicated for EUS-FNA, but it appears reasonable to follow the statement of ESGE (>10 mm). From the lessons learned in our healthcare setting, patients without morphological risk features can be safely followed with repeated imaging. Patients with one or more risk features should undergo EUS-FNA with fluid analysis. In those with a mucinous content, the risk of malignancy is high, and surgery should be recommended. However, there is still some risk that these patients will undergo unnecessary surgery but it appears to be balanced by capturing all high-risk neoplasia. For patients with a non-mucinous fluid, the cytological examination should explore the possibility of a serous lesion, or a pseudocyst. Whenever possible, it should be attempted to aspirate the entire liquid content to increase the yield of cytological examination. Next-generation sequencing of the cyst content for neoplastic DNA mutations emerges as a substantial step forward in improving the diagnostic accuracy of PCLs.

ORCID authors

T. Koller ORCID 0000-0001-7418-0073,

M. Tomáš ORCID 0000-0002-8666-5163,

V. Gal ORCID 0000-0001-9435-7825.

Submitted/Doručené: 31. 8. 2021

Accepted/Prijaté: 12. 10. 2021

Assoc. Prof. Tomáš Koller, PhD.

Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology

5th Department of Internal Medicine

Comenius University Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital Bratislava

Ružinovská 6

826 06 Bratislava

Sources

1. Jenssen C, Kahl S. Management of incidental pancreatic cystic lesions. Viszeralmedizin 2015; 31 (1): 14–24. doi: 10.1159/000375282.

2. Záruba P, Dvořáková T, Závada F et al. Is accurate preoperative assessment of pancreatic cystic lesions possible? Rozhl Chir 2013; 92 (12): 708–714.

3. Dumonceau J-M, Deprez PH, Jenssen C et al. Indications, results, and clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) -guided sampling in gastroenterology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline – Updated January 2017. Endoscopy 2017; 49 (7): 695–714. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-109021.

4. Lariño-Noia J, Iglesias-Garcia J, de la Iglesia-Garcia D et al. EUS-FNA in cystic pancreatic lesions: Where are we now and where are we headed in the future? Endosc ultrasound 2018; 7 (2): 102–109. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_93_17.

5. Repák R, Rejchrt S, Bártová J et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration with cyst fluid analysis in pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Hepatogastroenterology 2009; 56 (91–92): 629–635.

6. Sahai AV. Is EUS Here to stay? Accuracy is not an indication… Endosc ultrasound 2012; 1 (3): 117–118. doi: 10.7178/eus.03.001.

7. Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology 2012; 12 (3): 183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.04.004.

8. Scheiman JM, Hwang JH, Moayyedi P. American gastroenterological association technical review on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology 2015; 148 (4): 824–848.e22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.014.

9. Muthusamy VR, Chandrasekhara V, Acosta RD et al. The role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of cystic pancreatic neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 84 (1): 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.04.014.

10. European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas. European evidence-based guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gut 2018; 67 (5): 789–804. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316027.

11. Sahai AV, Chua TS, Paquin S et al. Analysis of variables associated with surgery versus observation in patients with pancreatic cystic lesions referred for endoscopic ultrasound. Endoscopy 2011; 43 (7): 591–595. doi: 10.1055/s-0030 - 1256489.

12. Simons-Linares CR, Yadav D, Lopez R et al. The utility of intracystic glucose levels in differentiating mucinous from non-mucinous pancreatic cysts. Pancreatology 2020; 20 (7): 1386–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2020.08.024.

13. Iguchi T, Shimizu A, Kubota K et al. Lymphoepithelial cyst mimicking pancreatic cancer: a case report and literature review. Surg case reports 2021; 7 (1): 108. doi: 10.1186/ s40792-021-01191-x.

14. Slobodkin I, Luu AM, Höhn P et al. Is surgery for serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas still indicated? Sixteen years of experience at a high-volume center. Pancreatology 2021; 21 (5): 983–989. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2021.03.020.

15. Sahai AV. Through-the-needle biopsy of pancreas cysts: Who, what, where, when, and mostly; why? Gastrointest Endosc 2020; 92 (1): 9–10. doi: https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2020.03.3752. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.03.3752.

16. Singhi AD, McGrath K, Brand RE et al. Preoperative next-generation sequencing of pancreatic cyst fluid is highly accurate in cyst classification and detection of advanced neoplasia. Gut 2018; 67 (12): 2131–2141. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313586.

17. Wang Y-Z, Lu J, Jiang B-L et al. Intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasm of the pancreas: A systematic review. Pancreatology 2019; 19 (6): 858–865. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2019.07.040.

Labels

Paediatric gastroenterology Gastroenterology and hepatology Surgery

Article was published inGastroenterology and Hepatology

2021 Issue 5-

All articles in this issue

- Gastrointestinal oncology – interdisciplinary cooperation

- Gastrointestinal oncology

- Kvíz z klinické praxe

- Pancreatic cancer screening: ready for prime time?

- Primárny lymfóm pankreasu – kazuistika

- Robotic-assisted surgery for colorectal and hepatopancreatobiliary neoplasms

- The role of molecular biology in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasias

- Status of robotic and minimally invasive foregut tumour surgery

- Diagnosis and endoscopic intervention in rare MALT lymphoma of the proximal jejunum

- Single center retrospective analysis of association of hidradenitis suppurativa and chronic inflammatory bowel disease

- How the treatment of gastrointestinal tract disorders may be influenced by the kidneys

- Komentář k doporučení Americké gastroenterologické asociace (AGA) pro léčbu středně těžké a těžké Crohnovy nemoci

- Recenze knih

- Životné jubileum prof. MUDr. Rudolfa Hyrdela, CSc

- Prof. MUDr. Marian Bátovský, CSc., MPH, 70-ročný

- Za Ivanom, kolegom, priateľom, ktorý nás učil žiť... MUDr. Ivan Bunganič (1952–2021)

- The selection from international journals

- Správná odpověď na předchozí kvíz Buried karcinom

- Kreditovaný autodidaktický test: gastrointestinální onkologie

- 7. kongres ČGS ČLS JEP 10.–12. listopadu 2021 Virtuální konference

- Videomaraton

- Endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration of pancreatic cystic lesions – a single-centre experience, and comparison with resection histology

- The potential of spectroscopy in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma – a pilot study

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Pancreatic cancer screening: ready for prime time?

- Status of robotic and minimally invasive foregut tumour surgery

- Primárny lymfóm pankreasu – kazuistika

- The role of molecular biology in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasias

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career