-

Medical journals

- Career

Validation of the Slovak Version of the SIBDQ Questionnaire in a Cohort of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients

Authors: Jalali Y; Sturdik I.; Adamcová M.; Krajcovicova A.; Huorka M.; Payer J.; Hlavaty T.

Authors‘ workplace: -5th Department of Internal Medicine Faculty of Medicine Comenius University and University Hospital Bratislava, Slovak Republic

Published in: Gastroent Hepatol 2019; 73(2): 138-142

Category:

doi: https://doi.org/10.14735/amgh2019138Overview

Background: The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ) is a widely used questionnaire for health-related quality of life assessment in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Although this questionnaire has been adopted and validated in several languages, it has not yet been validated in the Slovak language.

Aims: The aim of this study was to apply the methods and criteria used by several adaptation studies for assessing the validity and reliability of the adapted SIBDQ.

Methods: In this cross-sectional study, we collected data using 90 IBD questionnaires (ulcerative colitis (UC) 39 and Crohn’s disease (CD) 51 questionnaires) from 82 consecutive patients from the IBD centre at the Ružinov University Hospital in Bratislava. All patients were given three questionnaires: SIBDQ, Short Form survey (SF-36), Harvey-Bradshaw index (HBI) for CD patients and partial Mayo Score (pMayo) score for UC patients. Based on the data, we assessed the Slovak version of the SIBDQ for validity using the convergence rate of the Pearson correlation coefficient, reliability using Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency test, and acceptance and linguistic understandability using the Likert scale.

Results: The Slovak version of the SIBDQ was also highly correlated when compared to SF-36 (UC r = 0.87 and CD r = 0.81; both with p < 0.01), HBI (CD r = – 0.82; p < 0.01), and pMayo (UC r = – 0.86; p < 0.01). Reliability of the Slovak version of the SIBDQ was highly significant in both UC (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.96 for clinical presentation component and 0.85 for psychosocial limitation component) and CD (0.92 for clinical presentation component and 0.84 for psychosocial limitation component). Acceptability percentage of all SIBDQ questionnaires in UC and CD patients stayed constant at 100%. Linguistic understandability was evaluated with a seven-point Likert scale, which found that 93.15% of the patients strongly agreed that the questionnaire was linguistically understandable.

Conclusion: The Slovak version of the SIBDQ is a valid, reliable, and highly acceptable instrument to measure quality of life of patients with UC and CD.

Keywords:

SIBDQ – Ulcerative colitis – inflammatory bowel disease – SF-36 – pMayo – HBI

Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a measure commonly used in questionnaires to assess a patient’s perception of the impact of their disease on daily function. HRQoL instruments must include several properties to be useful, including acceptability, reliability, and validity [1]. Mitchell et al. [2] and Guyatt et al. [3] designed and validated the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ), an IBD-specific HRQoL for patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn‘s disease (CD). For more convenient daily clinical use, Love et al. [4] developed a short version of the questionnaire (SIBDQ). The application of the SIBDQ in patients with UC and CD has shown good reproducibility and better responsiveness than general health status measures [2–4].

The SIBDQ was designed and validated for a specific language and culture. The translation of this questionnaire into another language might impair its validity, even if the translation was comprehensive [5]. Therefore, translated questionnaires still require revalidation to demonstrate their conceptual equivalency to the original [6]. The SIBDQ has already been validated in the languages of many European countries (Spain, Great Britain, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, The Netherlands, Greece, Portugal, and Italy). Our aim was to investigate the validity, reliability, linguistic understandability, and acceptance of the Slovak version of the SIBDQ.

Materials and methods

In this cross-sectional study, a cohort of 82 IBD patients from the IBD centre at the Ružinov University Hospital in Bratislava were randomly selected. Subjects consisted of all consecutive eligible patients arriving at the IBD centre. We included data from 90 IBD questionnaires (51 CD and 39 UC patients). Patients were handed three questionnaires: the SIBDQ, Short form (SF-36), and HBI (Harvey-Bradshaw index) for CD patients or partial Mayo Score (pMayo) (for UC patient) at the time of their visit. The patients included in our study were in various stages of IBD or in remission. We determined the validity of the questionnaire data using the convergence correlation test with other relative indices of clinical activity (namely HBI for CD patients and pMayo for UC patients) for clinical components of the disease, and the SF-36 for the psychosocial limitation components of the disease. Data collected from the SIBD questionnaires were assessed for reliability using the internal consistency test (Cronbach alpha), evaluated separately for the clinical and psychosocial limitation component of the questionnaire. Acceptance of the questionnaire was assessed by examining the percentage of questions answered. Linguistic understandability was tested with a seven-point Likert test. We used Microsoft Excel for the data collection and analysis.

Results

Patient Characteristics

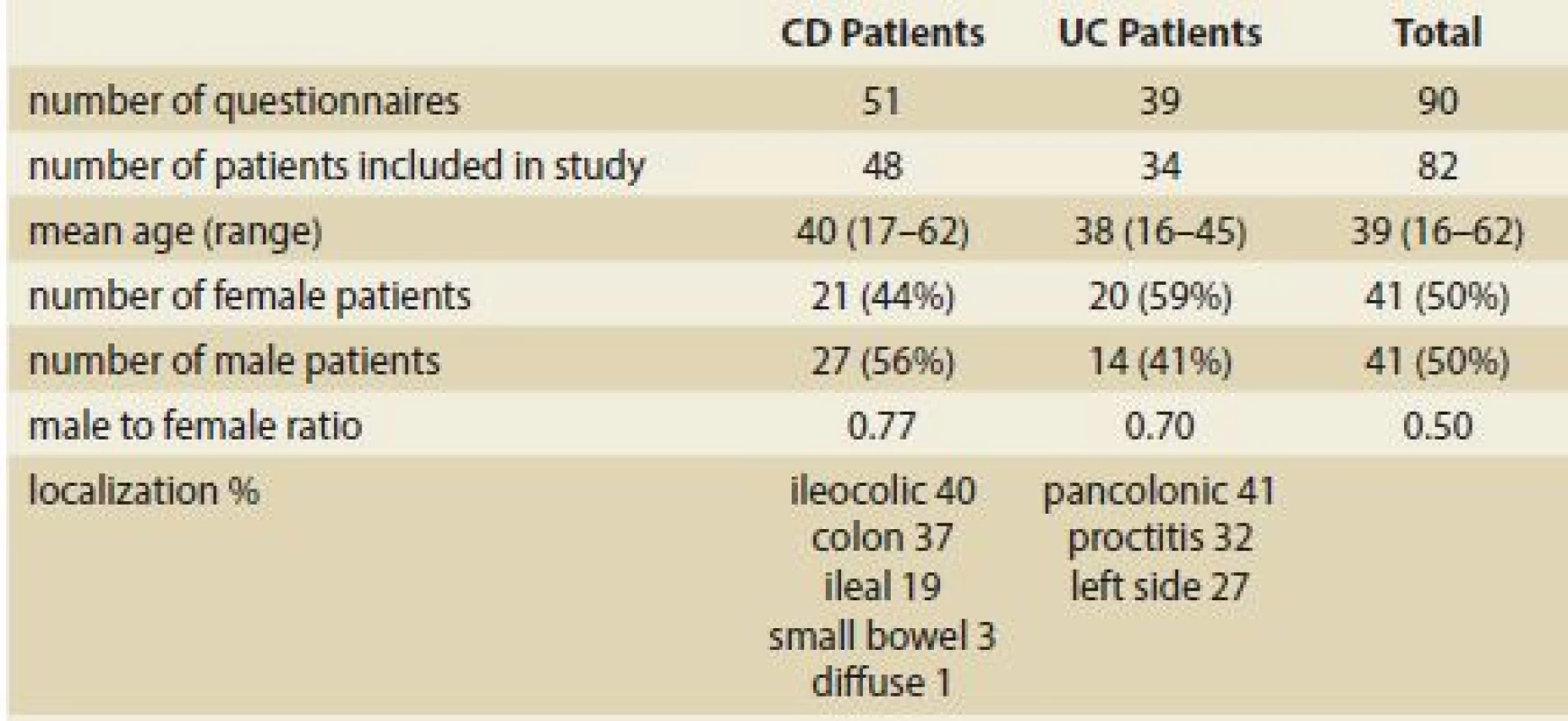

Patient characteristics, including demographic data and disease state, are summarised in Tab. 1.

1. Negative linear correlation between SIBDQ clinical presentation component, pMayo score and Harvey-Bradshaw index.

Graf 1. Negatívne lineárna korelácia medzi zložkou klinickej prezentácie v SIBDQ, skóre pMayo a Harvey-Bradshaw index.

SIBDQ – short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire, UC – ulcerative colitis, pMayo – partial Mayo score, HBI – Harve-Bradshaw index, CD – Crohn’s disease 1. Demographic data and disease state of patients.

Tab. 1. Demografické údaje a chorobný stav pacientov.

UC – ulcerative colitis, CD – Crohn’s disease Reliability

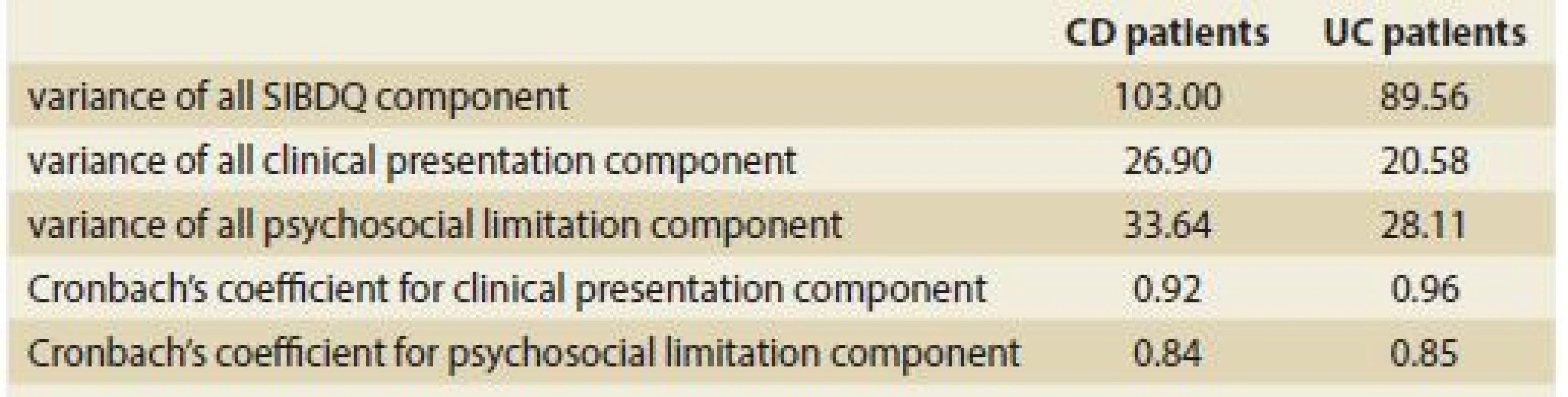

For the SIBDQ data from CD patients, Cronbach’s coefficient was 0.92 for the clinical presentation component and 0.84 for the psychosocial limitation component. For the SIBDQ data from UC patients, Cronbach’s coefficient was 0.96 for the clinical presentation component and 0.85 for the psychosocial limitation component. All relative data are summarised in Tab 2.

2. Cronbach’s coeficient for the clinical and psychosocial components of the SIBDQ completed by Crohn´s disease and ulcerative colitis patients.

Tab. 2. Cronbachov koeficient pre klinické a psychosociálne zložky SIBDQ vyplneného pacientmi s Crohnovou chorobou a ulceróznou kolitídou.

UC – ulcerative colitis, SIBDQ – Short Infl ammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire, CD – Crohn’s disease Acceptability and Language understandability

The acceptability percentage for the SIBDQ in UC and CD patients was 100%. The seven-point Likert test, used to evaluate linguistic understandability, showed that 93.2% of the patients strongly agreed that the questionnaire was linguistically understandable.

Convergence Validity

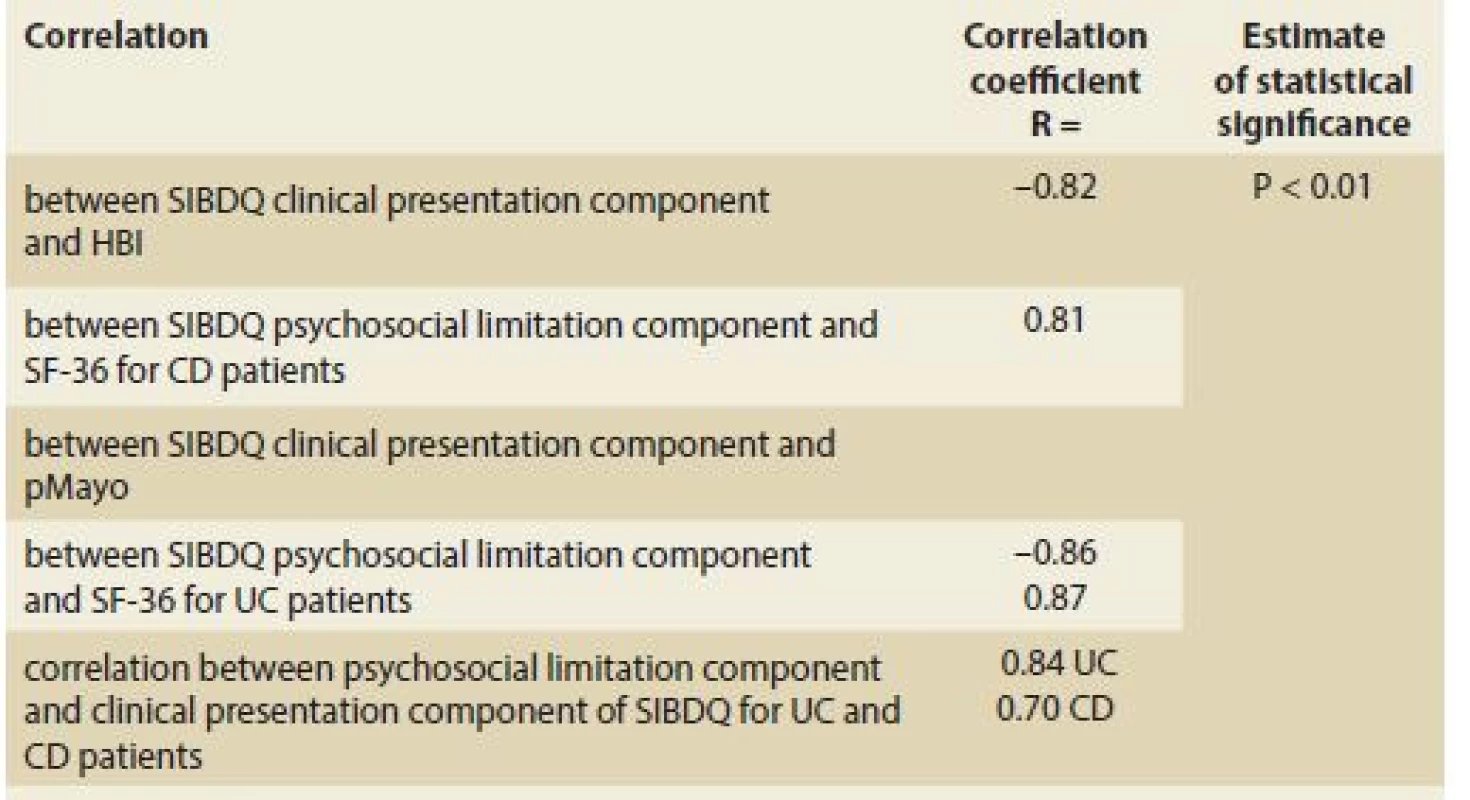

Pearson correlation coefficients between the SIBDQ, clinical indices (pMayo and HBI), and psychosocial questionnaire SF-36 were calculated separately for UC and CD patients. As shown in Tab. 3, the correlations between the clinical presentation component of the SIBDQ and the disease activity indices, psychosocial limitation component and SF-36 were statistically significant (P < 0.01). Correlations between the SIBDQ clinical presentation component and clinical indices of activity (namely pMayo and HBI) were large for both UC (r = – 0.86; p < 0.01) and CD (r = – 0.82; p < 0.01) (Graph 1) patients. Similarly, we found large correlations between the psychosocial limitation component of the SIBDQ and the SF-36 (UC: r = 0.87 and CD: r = 0.81; both p < 0.01) (Graph 2A and 2B). Correlations between the clinical presentation component and psychosocial limitation component of the SIBDQ questionnaires were large for UC (r = 0.84) and CD (r = 0.70) patients (Tab. 3).

3. Pearson correlation coeficient between the SIBDQ and Harvey-Bradshaw index, pMayo score, and Short Form SF-36.

Tab. 3. Pearsonův korelační koeficient mezi SIBDQ a Harvey-Bradshaw indexem, pMayo skóre a Short Form SF-36.

(R) – Pearson coefficient, CD – Crohn’s disease, UC – ulcerative colitis, SIBDQ – Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire, SF-36 – Short Form survey, pMayo – partial Mayo score, HBI – Harvey Bradshaw index 2. Linear correlation between the SIBDQ and SF-36 in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients, respectively.

Graf 2. Lineárna korelácia medzi SIBDQ a SF-36 u pacientov s ulceróznou kolitídou a Crohnovou chorobou.

SIBDQ – short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire, UC – ulcerative colitis, SF-36 – Short Form, CD – Crohn’s disease Discussion

The present study analysed the psychosocial limitation and clinical presentation properties of the Slovak version of the SIBDQ. The results of our study suggest that the Slovak version of the SIBDQ has good convergence validity, reliable internal consistency, acceptability, and linguistic understandability. The validity results of the SIBDQ are similar for UC and CD patients, which suggests that the Slovak version of the SIBDQ is an equally appropriate clinical tool to measure the HRQoL in IBD patients in Slovakia. The SIBDQ has already been successfully validated and translated into several other languages without loss in content validity, reproducibility, and responsiveness [7–9].

When comparing our results with those described by other authors, some methodological differences should be considered. For instance, the studies may differ in the Likert scale range used (5-vs. 7-point) [7] and whether the 32-item IBDQ or the SIBDQ version is used [8]. To test the validity of the Slovak version of the SIBDQ, we compared our questionnaire with clinical indices of activity (namely HBI for CD patients and pMayo for UC patients) for clinical presentation, and with the SF-36 questionnaire for psychosocial limitation of the disease. In both UC and CD patients, the clinical presentation component and psychosocial limitation component of the SIBDQ was well correlated (with statistical significance P < 0.01) with clinical indices and scores of SF-36 (correlation coefficient of r = – 0.82 between SIBDQ and HBI; 0.81 between SIBDQ and SF-36 in CD patients; – 0.86 between SIBDQ and pMayo; and 0.87 between SIBDQ and SF-36 for UC patients). In our study, the internal consistency reliability coefficient was high for both clinical presentation and psychosocial limitation component in both UC and CD patients (namely Cronbach’s coefficient of 0.92 for clinical presentation and 0.84 for psychosocial limitation in CD patients and 0.96 for clinical presentation and 0.85 psychosocial limitation in UC patients). Considering that internal consistency coefficients above 0.84 are generally accepted as satisfactory [10], our results suggest that the Slovak version of the SIBDQ has excellent internal consistency for both UC and CD patients. Our data show that the Slovak version of the SIBDQ has a high rate of acceptability and linguistic understandability for IDB patients.

In conclusion, the results of the validation of the Slovak version of the SIBDQ support its validity, reliability, acceptability, and linguistic understandability. In addition, our study shows that the high clinical presentation properties of the test are comparable for UC and CD patients. Therefore, the test can be applied for the measurement of the HRQoL in either disease.

Submitted: 20. 11. 2018

Accepted: 3. 2. 2019

MUDr. Yashar Jalali

5th Department of Internal Medicine

Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University and University Hospital Bratislava

Ruzinovska 6

826 06 Bratislava

Slovak Republic

Sources

1. Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med 1993; 118 (8): 622–629.

2. Mitchell A, Guyatt G, Singer J et al. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 1988; 10 (3): 306–310.

3. Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 1989; 96 (3): 804–810.

4. Love JR, Irvine EJ, Fedorak RN. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 1992; 14 (1): 15–19.

5. Badía X, García-Losa M, Dal-Ré R. The language translation and harmonization of the International Prostate Symptom Score: developing a methodology for multinational clinical trials. Eur Urol 1997; 31 (2): 129–140.

6. Patrick DL, Wild DJ, Johnson ES et al. Cross-cultural validation of quality of life measures. In: Orley J, Kuykev W (eds). Quality of life assessment. Berlin: Springer 1995 : 19–32.

7. de Boer AG, Wijker W, Bartelsman JF. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: cross-cultural adaptation and further validation. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7 (11): 1043–1050.

8. Russel MG, Pastoor CJ, Brandon S et al. Validation of the Dutch translation of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ): a health-related quality of life questionnaire in inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion 1997; 58 (3): 282–288.

9. Kalafateli M, Triantos C, Theocharis G et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a single-center experience. Ann Gastroenterol 2013; 26 (3): 243–248.

10. McDowell I, Neweell C. The theoretical and technical foundations of health measurement. In: McDowell I, Neweell C (eds). Measuring Health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires. New York: Oxford University Press 1987 : 12–35.

Labels

Paediatric gastroenterology Gastroenterology and hepatology Surgery

Article was published inGastroenterology and Hepatology

2019 Issue 2-

All articles in this issue

- Clinical practice guidelines for chronic hepatitis C virus infection

- Inflammatory bowel disease and male fertility

- Ectopic pancreas as a cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding

- A gastric Dieulafoy’s lesion

- Involvement of the gastrointestinal tract in amyloidosis: when to think about it and how to diagnose

- Part 2 – Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases in the Czech population: available data sources, prevalence of treated patients and overall mortality

- Laparoscopic liver resection for alveolar echinococcosis

- Validation of the Slovak Version of the SIBDQ Questionnaire in a Cohort of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- A gastric Dieulafoy’s lesion

- Involvement of the gastrointestinal tract in amyloidosis: when to think about it and how to diagnose

- Ectopic pancreas as a cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding

- Inflammatory bowel disease and male fertility

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career