-

Medical journals

- Career

Comparison of obstetrical interventions in women with vaginal and cesarean section delivered: cross-sectional study in a reference tertiary center in the Northeast of Brazil

Authors: M. Q. Medeiros 1; P. H. M. Lima 1; C. L. C. Augusto 1; B. Junior A. Viana 2; B. A. K. Pinheiro 1; A. B. Peixoto 3,4,5; Edward Araujo Júnior 3; C. F. H. Carvalho 1

Authors‘ workplace: Maternal Fetal-Medicine Service, Assis Chateaubriand Maternity, Federal University of Ceará (UFC), Fortaleza-CE, Brazil 1; Research Support Service, Teaching and Research Management, University Hospitals, Federal University of Ceará (UFC), Fortaleza-CE, Brazil 2; Department of Obstetrics, Paulista School of Medicine – Federal University of São Paulo (EPM-UNIFESP), São Paulo-SP, Brazil 3; Discipline of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Federal University of Triângulo Mineiro (UFTM), Uberaba-MG, Brazil 4; Gynecology and Obstetrics Service, Mário Palmério University Hospital, University of Uberaba (UNIUBE), Uberaba-MG, Brazil 5

Published in: Ceska Gynekol 2019; 84(3): 201-207

Category:

Overview

Objective: To compare the performance of obstetrical interventions and maternal and perinatal outcomes between vaginal and cesarean delivery routes in pregnant women at normal risk.

Type of article: Original article.

Desing: Cross-sectional study with 421 participants admitted for spontaneous or induced labor with full-term singleton gestations and fetuses weighing between 2,500 and 4,499 g.

Setting: Maternal Fetal-Medicine Service, Assis Chateaubriand Maternity, Federal University of Ceará (UFC), Fortaleza-CE, Brazil.

Methods: The instrument of data collection was divided into socio-demographic, clinical, and obstetric characteristics; data of labor and delivery; maternal morbidity; maternal outcome and perinatal outcomes. Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to verify associations between the groups.

Results: The mean age was 22.8 ± 6.0 (vaginal) and 22.9 ± 4.9 (cesarean section). Overall, 44.5% of vaginal deliveries and 85.5% of cesarean sections were monitored electronically (p < 0.001). Immediate skin-to-skin contact (84.1%) and first-hour breastfeeding (80.4%) were more frequent in vaginal deliveries compared with cesarean deliveries (27% vs. 61.0%, p < 0.001). The prevalence of puerperal infections was 1.2% (vaginal) and 5.0% (cesarean section) with a p value of 0.02; 40% of cesarean-delivered newborns and 9.7% of vaginally-delivered newborns were referred to the neonatal intensive care unit (p < 0.001).

Conclusion: The cesarean section was associated with a lower frequency of useful practices, a higher frequency of harmful practices, worse neonatal outcomes, and a higher rate of postpartum infections.

Keywords:

childbirth – spontaneous vaginal delivery – health services

INTRODUCTION

The institutionalization and medicalization of health has been responsible for several changes in the care provided to women and their unborn children at the time of delivery. Here we highlight cesarean section, one of the most invasive interventions and that alters the natural course of childbirth the most [16].

Brazil is among the countries with the highest cesarean rates in the world with rates that reach 53% and those that are higher in private services [2]. However, the World Health Organization (WHO) advocates performing a cesarean section only when there is indication due to maternal and fetal clinical reasons [11, 20]. Unnecessary interventions during labor and delivery continue to be performed even against recommendations. In Brazil, a study conducted in 2014 with 6,740 women found high frequencies of peripheral venipuncture, oxytocin use, amniotomy, lithotomy position, Kristeller maneuver, and episiotomy [4].

Interventions such as labor induction and the use of epidural analgesia increase the likelihood of cesarean section [19]. In addition, interventions such as the admission of pregnant women in the latent phase of childbirth are also associated with higher rates of cesarean section [15].

In 1996, WHO issued a practical guide for the purpose of assisting vaginal delivery as opposed to medicalization and over-intervention [13]. Since then, the most commonly used practices during labor and delivery have been identified to establish the standards of good practice based on scientific evidence.

The objective of the present study was to compare the use of obstetrical interventions and maternal and perinatal outcomes between the vaginal and cesarean delivery routes in patients at normal risk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective cross-sectional study of pregnant women assisted at the Maternidade Escola Assis Chateaubriand, Fortaleza-CE, Brazil, from April 2014 to January 2015. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Ceará No. 957.05018, and no consent form was necessary because of its retrospective nature.

The population of this study consisted of pregnant women and their unborn children with gestational age between 37 and 42 weeks, as confirmed by the method described by Capurro et al. [3]. The sample included patients admitted to the obstetric center for spontaneous or induced labor with a live fetus, serological tests for HIV and syphilis, without history of diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, or chronic hypertension, and newborns with birth weight between 2,500 and 4,499 g. The pregnant women were considered at normal risk similar to the study by Carmo Leal et al. [4]. Patients who had twin pregnancies or elective cesarean sections were excluded.

The selection of the cases was done using the database query. The study initially included 729 women; however, 172 patients were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria and medical records for 136 patients were not available. Therefore, 421 women and 421 newborns were considered for the final statistical analysis. There were no maternal or perinatal deaths. The women were divided into two groups, the first group included 321 women who delivered vaginally and the second group included 100 women who delivered by cesarean section.

The following parameters were evaluated: socio-demographic, clinical, and obstetric characteristics; labor and delivery data; maternal morbidity; maternal outcome; characteristics of the institution; obstetric practices; and perinatal outcomes. Data related to the puerperium were recorded until the day of hospital discharge up to a maximum of 45 days postpartum. Data related to the newborns were recorded until hospital discharge up to a maximum of 28 days after birth.

To calculate the sample size, the number of births that occurred at the institution from April 2014 to March 2015 (4,099) was considered. Based on the proportion of the type of delivery, with an error margin of 5% and a confidence level of 95%, there were 351 deliveries. Approximately 20% was added to this number to compensate for losses of information and excluded pregnant women.

The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 22.0 software (SPSS In., Chicago, IL, USA). Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to verify the associations between groups. The level of significance, p < 0.05, was used.

RESULTS

The study included 421 women, 321 (76.2%) of whom delivered vaginally and 100 (23.8%) delivered by cesarean section. The mean age of the women who delivered vaginally was 22.8 ± 6.0 years (13–44) and the mean age of the women who delivered by cesarean section was 22.9 ± 4.9 years (14–36) without any statistical difference (p = 0.36). The gestational age estimated using the method described by Capurro et al. [3] ranged from 37 to 41 complete weeks in both groups with a mean of 38.9 ± 0.89 for vaginal delivery and 39.2 ± 0.95 for cesarean section (p = 0.02).

The number of previous deliveries among the women studied ranged from 1 to 5 with a mean of 1.78 ± 1.17 (vaginal delivery) and 1.27 ± 0.52 (cesarean section) with a p value of 0.038. Primiparous women accounted for more than half of the sample (52.0%) and 28% of the women were in their second pregnancy. Overall, 56.1% of the women who delivered vaginally were primiparous, whereas this percentage was 67% among women who had a cesarean section (p = 0.052). The percentage of women who had had a previous cesarean section was 3.7% among women who delivered vaginally and 24% among women who had a cesarean section (p < 0.001).

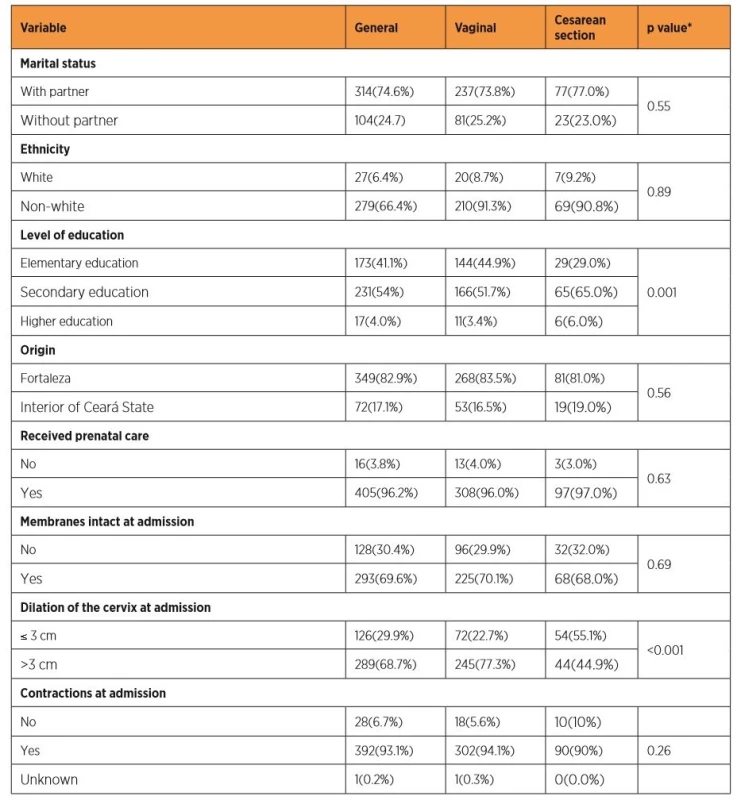

The mean cervical dilation at admission was 5.4 ± 2.39 cm for vaginal delivery and 3.5 ± 1.91 cm for cesarean section (p < 0.001); 22.7% of the women who progressed to vaginal delivery and 55.1% of those who progressed to cesarean section arrived at the emergency room with a cervical dilation of ≤ 3 cm (p < 0.001). Data on maternal socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 1.

1. Maternal demographic and obstetric characteristics by delivery route

*Pearson’s chi-square Skin-to-skin contact immediately after delivery was present in 84.1% of vaginal deliveries, whereas it was present in 27% of cases of cesarean section (p < 0.001). Breastfeeding during the first hour after delivery occurred in 64.5% of vaginal deliveries and in 6% of cesarean sections (p < 0.001). Overall, 31.2% of the vaginal deliveries were performed by nurses and 5.9% had a nurse as a part of the multiprofessional team.

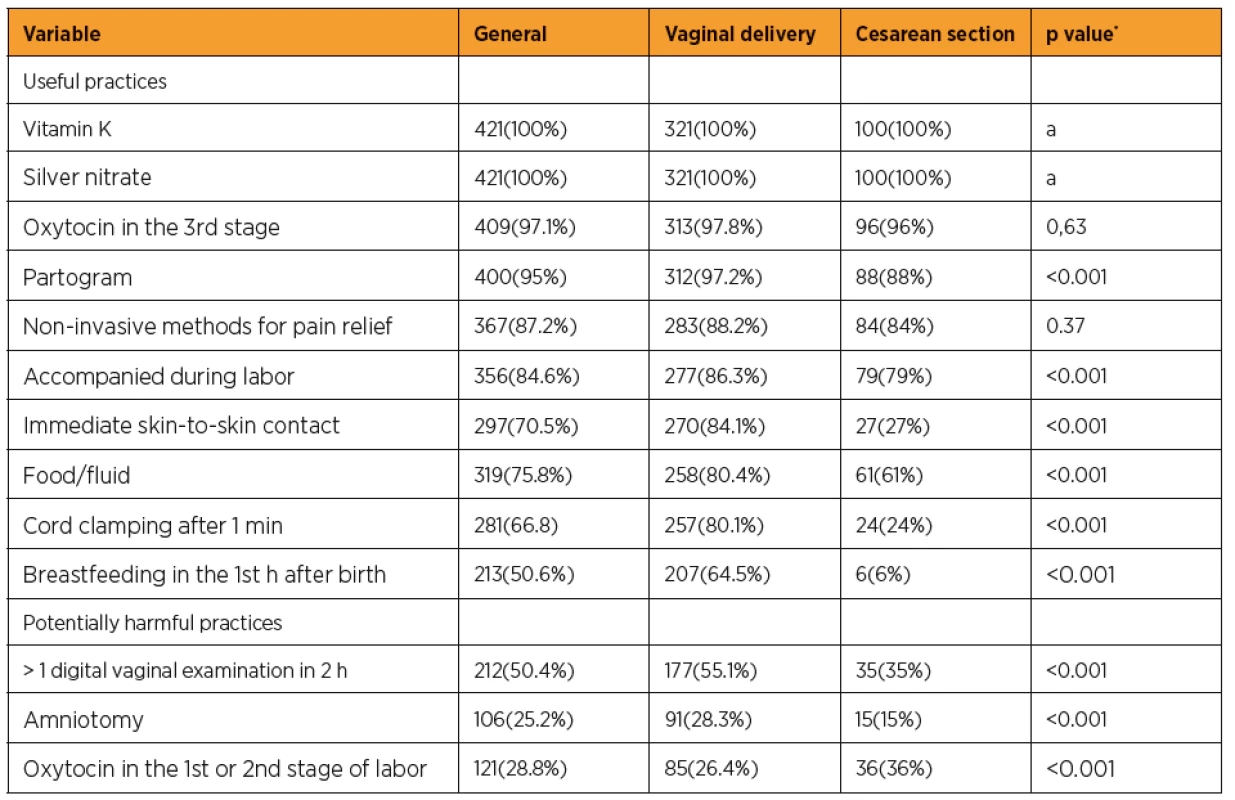

Table 2 shows the association between the obstetric interventions of category A [4], which are proven to be useful and should be encouraged, and those of category B [8], which are ineffective practices and should not be routinely used and the delivery route. The frequencies of episiotomy and vaginal laceration, which were considered only for women having vaginal delivery, were 15.3% and 57.6%, respectively; 50% of which were first-degree lacerations. Among the techniques that are often used inappropriately, fetal electronic monitoring was performed in 228 (54.2%) of all study participants, i.e., in 143 (44.5%) of vaginal deliveries and in 85 (85.0%) of cesarean sections (p < 0.001).

2. Association between obstetric interventions and delivery route

a = No estimate was calculated because the value is a constant.

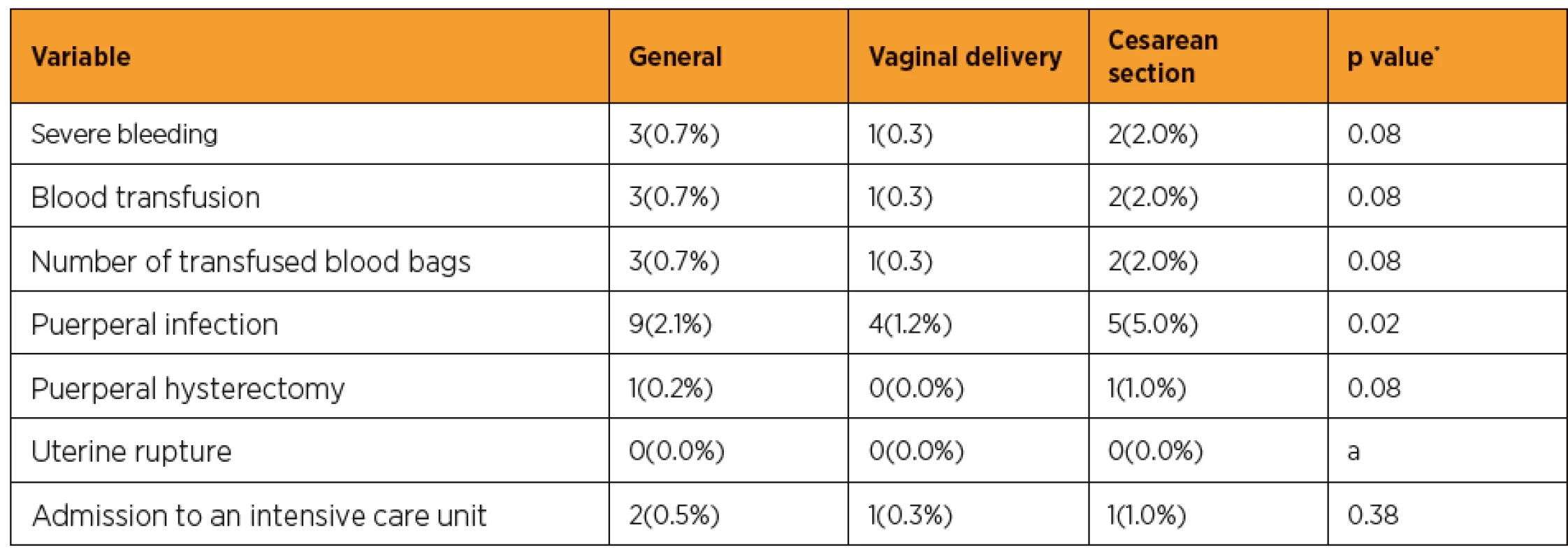

*Pearson’s chi-squareIt was observed that 25.9% of vaginal deliveries and 22.0% of cesarean deliveries occurred on weekends, and there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.43). In addition, there was no significant difference regarding the shift (day: from 07 : 00 a.m. to 7 : 00 p.m. and night: from 7 : 00 p.m. to 7 : 00 a.m.) during which deliveries occurred with 55.5% of vaginal deliveries and 53.0% of cesarean deliveries being performed during the daytime shift (p = 0.66). The maternal results are presented in Table 3.

3. Comparison of maternal results between the vaginal and cesarean delivery groups

a = No estimate was calculated because the value is a constant.

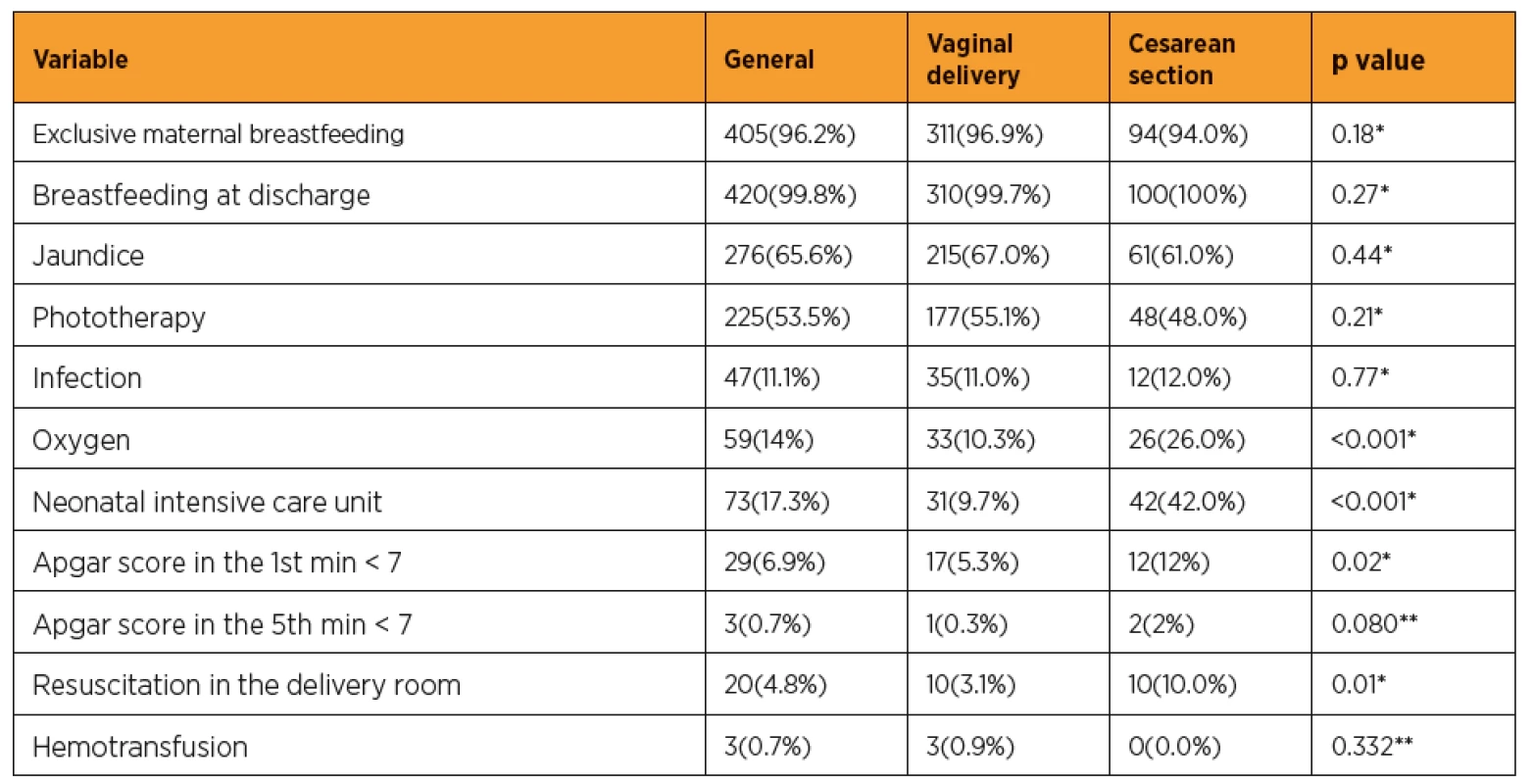

*Pearson’s chi-squareMore than 40% of newborns in the cesarean group and 9.7% in the vaginal delivery group were referred to the neonatal intensive care unit (ICU) (p < 0.001). The Apgar score at 1 minute was <7 in 12% of cesarean sections and in 5.3% of vaginal deliveries (p = 0.02). Overall, 10% of cesarean-delivered newborns and 3.1% of vaginally-delivered newborns required resuscitation in the delivery room (p = 0.001) (Table 4).

4. Comparison of neonatal outcomes between the vaginal and cesarean delivery groups

*Pearson’s chi-square; **Fisher’s exact test DISCUSSION

The cesarean rate found in the present study was 23.8%, which was less than half of the state and national rates. In Brazil, this rate has been rising steadily since the mid-1990s; in 2009, it surpassed the rate of vaginal births in the country [6]. More than half of women who delivered via cesarean section (55.1%) were admitted to the service during the first stage of labor, a factor described as predisposing to unnecessary interventions [15, 18].

Carmo Leal et al. [4] reported that there was a higher rate of cesarean sections among women with higher levels of education, which corroborates our findings, i.e., a statistically significant difference between the vaginal delivery group and the cesarean section group with 55.1% and 71% of pregnant women with intermediate or higher education levels, respectively. A high educational level is associated with a higher socioeconomic level; therefore, these pregnant women seek private health services to have their cesarean deliveries. In a recent study, Almeida et al. [1] observed a 91.8% cesarean rate in a private service in Vitória, Espírito Santo, with 17.1% being elective.

In the study by Carmo Leal et al. [4], less than one-third of pregnant women at normal risk had food and used non-pharmacological procedures for pain relief during labor, and 45% were monitored with partogram. In contrast, 75.8% of the pregnant women in the present study had food, 87.2% received non-invasive methods for pain relief, and 95% were monitored by partogram. In the study by Oliveira et al. [12]., 75.7% of cases had venous hydration as a routine practice in the course of labor and 21.4% had a companion with them. In the present study, a companion was present in 86.3% of deliveries.

The frequencies of episiotomy and laceration were 15.3% and 57.6%, respectively; 50% were first-degree lacerations. In a study involving 11 institutions in the state of Sergipe, the episiotomy rate was 43.9% and that of Kristeller maneuver was 31.7%. In a Canadian study, Chalmers et al. [5] observed an episiotomy rate of 20.7% and a Kristeller maneuver rate of 19.1%. In a recent Brazilian study involving 222 normal risk vaginal deliveries without episiotomy, the rate of lacerations was 79.8%, 47% being of the first degree [10].

With regard to postpartum infection rates, we observed rates of 1.2% and 5.0% for vaginal and cesarean deliveries, respectively. In a Nepalese study, the rates of fever and postpartum infections associated with cesarean section delivery were 18.8% and 4.8%, respectively [9]. With regard to neonatal outcomes, 26% of post-cesarean newborns and 10.3% of post-vaginal newborns required oxygen and 10.0% of cesarean-delivered newborns and 3.1% of vaginally-delivered newborns required resuscitation in the delivery room.

According to d’Orsi et al. [7], carrying out an excessive number of digital vaginal examinations is an inadequate practice. In the present study, more than one digital vaginal examination in two hours was recorded in 55.1% of vaginal deliveries and in 35% of cesarean deliveries.

Skin-to-skin contact immediately after delivery was observed in 84.1% of vaginal deliveries and 27% of cesarean deliveries. Skin-to-skin contact is associated with an early initiation of breastfeeding. In Bangladesh, cesarean-delivered newborns had a 67% lower rate of early initiation of breastfeeding than vaginally-delivered newborns [17].

CONCLUSION

In summary, useful practices were more prevalent among women submitted to vaginal delivery. Women having cesarean sections were more likely to undergo harmful obstetric interventions and fewer useful interventions, which may in part justify the increased cesarean indications and worse maternal and neonatal outcomes. There was a higher prevalence of postpartum infections and worse neonatal outcomes in this group of women.

Prof. Edward Araujo Júnior, PhD

Rua Belchior de Azevedo, 156 apto. 111 Torre Vitoria

CEP 05089-030

São Paulo–SP, Brazil

e-mail: araujojred@terra.com.br

Sources

1. Almeida, MA., Araujo Júnior, E., Camano, L., et al. Impact of cesarean section in a private health service in Brazil: indications and neonatal morbidity and mortality rates. Ces Gynek, 2018, 83(1), p. 4–10.

2. Alonso, BD., Silva, FMBD., Latorre, MDRDO., et al. Caesarean birth rates in public and privately funded hospitals: a cross-sectional study. Rev Saude Publica, 2017, 51, p. 101.

3. Capurro, H., Korichzky, S., Fonseca, O., Caldeiro-Barcia, R. A simplified method for diagnosis of gestational age in the newborn infant. J Pediatr, 1978, 93(1), p. 20–122.

4. Carmo Leal, MD., Pereira, AP., Domingues, RM., et al. Obstetric interventions during labor and childbirth in Brazilian low-risk women. Cad Saude Publica, 2014, 30, Suppl. 1, p. S1–16.

5. Chalmers, B., Kaczorowski, J., Levitt, C., et al. Use for routine interventions in vaginal labor and birth: findings from the maternity experiences survey. Birth, 2009, 36(1), p. 13–25.

6. Domingues, RM., Szwarcwald, CL., Souza Junior, PR., Leal Mdo, C. Prevalence of syphilis in pregnancy and prenatal syphilis testing in Brazil: birth in Brazil study. Rev Saude Publica, 2014, 48(5), p. 766–774.

7. d’Orsi, E., Chor, D., Giffin, K., et al. [Quality of birth care in maternity hospitals of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil]. Rev Saude Publica, 2005, 39(4), p. 645–654.

8. Gomes, K. Intervenções obstétricas realizadas durante o trabalho de parto e parto em uma maternidade de baixo risco obstétrico, na cidade de Ribeirão Preto. Ribeirão Preto. Tese [Mestrado] – Escola de Enfermagem de Ribeirão Preto; 2011. [cited 2012 Jan 12]. Available from: http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/22/22133/tde-28112011-163517/pt-br.php.

9. Gurung, P., Malla, S., Lama, S., et al. Caesarean section during second stage of labor in a tertiary centre. J Nepal Health Res Counc, 2017, 15(2), p. 178–181.

10. Lins, VML., Katz, L., Vasconcelos, FBL., et al. Factors associated with spontaneous perineal lacerations in deliveries without episiotomy in a university maternity hospital in the city of Recife, Brazil: a cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018 Apr 18 : 1-6. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1457639. [Epub ahead of print].

11. Norum, J., Svee, TE. Caesarean section rates and activity-based funding in Northern Norway: A model-based study using the World Health Organization’s recommendation. Obstet Gynecol Int, 2018, 2018, p. 6764258.

12. Oliveira, MI., Dias, MA., Cunha, CB., Leal Mdo, C. [Quality assessment of labor care provided in the Unified Health System in Rio de Janeiro, Southeastern Brazil, 1999–2001]. Rev Saude Publica. 2008, 42(5), p. 895–902.

13. Organização Mundial da Saúde. Assistência ao parto normal: um guia prático. Genebra: OMS, 1996.

14. Prado, D., Mendes, RB., Gurgel, RQ., et al. Practices and obstetric interventions in women from a state in the Northeast of Brazil. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2017, 63(12), p. 1039–1048.

15. Rota, A., Antolini, L., Colciago, E., et al. Timing of hospital admission in labour: latent versus active phase, mode of birth and intrapartum interventions. A correlational study. Women Birth, 2018, 31(4), p. 313–318.

16. Silva, ALAD., Mendes, ADCG., Miranda, GMD., Souza, WV. [Quality of care for labor and childbirth in a public hospital network in a Brazilian state capital: patient satisfaction]. Cad Saude Publica. 2017, 33(12), p. e00175116.

17. Singh, K., Khan, SM., Carvajal-Aguirre, L., et al. The importance of skin-to-skin contact for early initiation of breastfeeding in Nigeria and Bangladesh. J Glob Health, 2017, 7(2), p. 020505.

18. Tilden, EL., Lee, VR., Allen, AJ., et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of latent versus active labor hospital admission for medically low-risk, term women. Birth, 2015, 42(3), p. 219–226.

19. Villar, J., Carroli, G., Zavaleta, N., et al. Maternal and neonatal individual risks and benefits associated with caesarean delivery: multicentre prospective study. BMJ, 2007, 335(7628), p. 1–11.

20. World Health Organization United Nations Population Fund; United Nations Children’s Fund; Mailman School of Public Health. Monitoring emergency obstetric care: a handbook. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009.

Labels

Paediatric gynaecology Gynaecology and obstetrics Reproduction medicine

Article was published inCzech Gynaecology

2019 Issue 3-

All articles in this issue

- Individualization of surgical management of cervical cancer stages IA1, IA2

- Endometrial Receptivity Analysis – a tool to increase an implantation rate in assisted reproduction

- NK cells not only in endometrium but also in ovulatory cervical mucus in patients with decreased fertility

- Echogenic foci in fetal heart from a pediatric cardiologist‘s point of view

- Prenatal diagnosis of Noonan syndrome in fetuses with increased nuchal translucency and a normal karyotype

- Locally advanced colorectal cancer in pregnancy

- Primary synovial sarcoma of the ovary and Fallopian tube – case report and review of the literature

- The changes in FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri

- Impact of 3D ultrasound on fetal CNS examination

- The risk of thromboembolism in relation to in vitro fertilization

- Vaginismus – who takes interest in it?

- Uterine adenomyosis: pathogenesis, diagnostics, symptomatology and treatment

- Comparison of obstetrical interventions in women with vaginal and cesarean section delivered: cross-sectional study in a reference tertiary center in the Northeast of Brazil

- Czech Gynaecology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Uterine adenomyosis: pathogenesis, diagnostics, symptomatology and treatment

- Echogenic foci in fetal heart from a pediatric cardiologist‘s point of view

- Vaginismus – who takes interest in it?

- Locally advanced colorectal cancer in pregnancy

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career