-

Medical journals

- Career

The Impact of High Protein Nutritional Support on Clinical Outcomes and Treatment Costs of Patients with Colorectal Cancer

Authors: V. Maňásek 1; K. Bezděk 2; A. Foltýs 3; K. Klos 4; J. Smitka 5; D. Smehlik 6

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Oncology, Complex Oncological Center Nový Jičín, Czech Republic 1; Nutritional Ambulance, Department of Anesthesiology, Hospital Nový Jičín, a. s., Czech Republic 2; Surgery Clinic of Medical Faculty Ostrava and Faculty Hospital Ostrava, Czech Republic 3; Department of Surgery, Vítkovice Hospital a. s., Czech Republic 4; Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition, Praha, Czech Republic 5; Revírní bratrská pokladna, Health Insurance Company, Ostrava, Czech Republic 6

Published in: Klin Onkol 2016; 29(5): 351-357

Category: Original Articles

doi: https://doi.org/10.14735/amko2016351Overview

Background:

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the impact of high protein oral nutrition support (ONS) on clinical outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC). The secondary aim was to compare the cost of treatment and length of stay (LoS) for CRC patients taking high protein ONS vs. patients on conventional nutritional support.Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted on adult patients with CRC undergoing colorectal surgery. Informed consent was obtained before the study. The study group (SG; n = 52) was instructed to take high protein ONS (600 kcal, 40 g protein per day) in addition to a normal diet for at least 10 days before and two weeks after surgery. Data from the comparative group (CG; n = 105) were collected retrospectively.Results:

A relative reduction in the frequency of the following complications was observed in SG: wound dehiscence (2.2 times lower), infections (4.3 times lower), anastomosis dehiscence (2.0 times lower), and rehospitalization (1.7 times lower). The mean LoS was shorter in SG (9.4 ± 4.97 vs. CG 12 ± 6.4 days), which resulted in significantly lower treatment costs during hospitalization (SG 479 vs. CG 538 EUR; p = 0.01) and at six months after surgery (SG 4,862 vs. CG 6,456 EUR).Conclusion:

Pre - and postoperative high protein ONS reduces LoS, treatment costs, postoperative complications, and re-hospitalizations in CRC, regardless of initial nutritional status.Key words:

high protein oral nutritional support – colorectal cancer – perioperative careIntroduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common forms of cancer in Europe, with over 447,000 new cases diagnosed per year [1]. Yearly incidence rates vary from 21 (Greece) to 64 (Czech Republic) per 100,000 [2]. Several factors predispose individuals to an increased risk for the disease, including genetic background, age, male sex, presence of polyps, ulcerative colitis or consuming high fat diet. Between 2000 and 2010, CRC mortality rates fell in the European Union (EU) from 22.2 to 20.5 per 100,000, reflecting increasing effectiveness of cancer treatment (including screening, diagnosis) as well as incidence changes. This trend was not uniform across the EU [2]; however, the Czech Republic and Germany see relatively large declines in mortality, while having the highest screening rates [2]. Hungary, while also seeing a decrease, continues to have the highest mortality for CRC, followed by the Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic [2]. However, overall survival (OS) of treated patients in the Czech Republic is similar to developed countries (30 months in case of metastatic CRC). High mortality rate might be caused by late diagnosis (IVth clinical stage). Population-based data on malignant tumors are available in the Czech Republic. The Czech National Cancer Registry (CNCR) was instituted in 1977 and contains information collected over a 34-year period of standardized registration covering 100% of cancer diagnoses for the entire Czech population. The CNCR analysis is supported by demographic data and by the Death Records Database. An overview of epidemiology of malignant tumors in the Czech population is available on-line at www.svod.cz [3].

Survival prospects deteriorate as the disease develops, the 5-year relative survival rates of patients suffering from colon cancer, per disease stage, are: I 92%, IIA 87%, IIB 63%, IIIA 89%, IIIB 69%, IIIC 53%, IV 11%, resp. For rectal cancer, the relative survival rates are as follows: I 87%, IIA 80%, IIB 49%, IIIA 84%, IIIB 71%, IIIC 58%, IV 12%, resp. [4]. Numbers of early diagnosed cases are generally insufficient, even in the case of highly prevalent cancers such as CRC (only 46.1% of incident cases are diagnosed at stage I or II, according to recent data in the Czech Republic) [3]. Total mortality in the EU due to CRC is expected to rise from 212,000 deaths per year in 2008 to 248,000 in 2020 [2]. Therefore, improvements in the management of CRC are a high priority for every healthcare system.

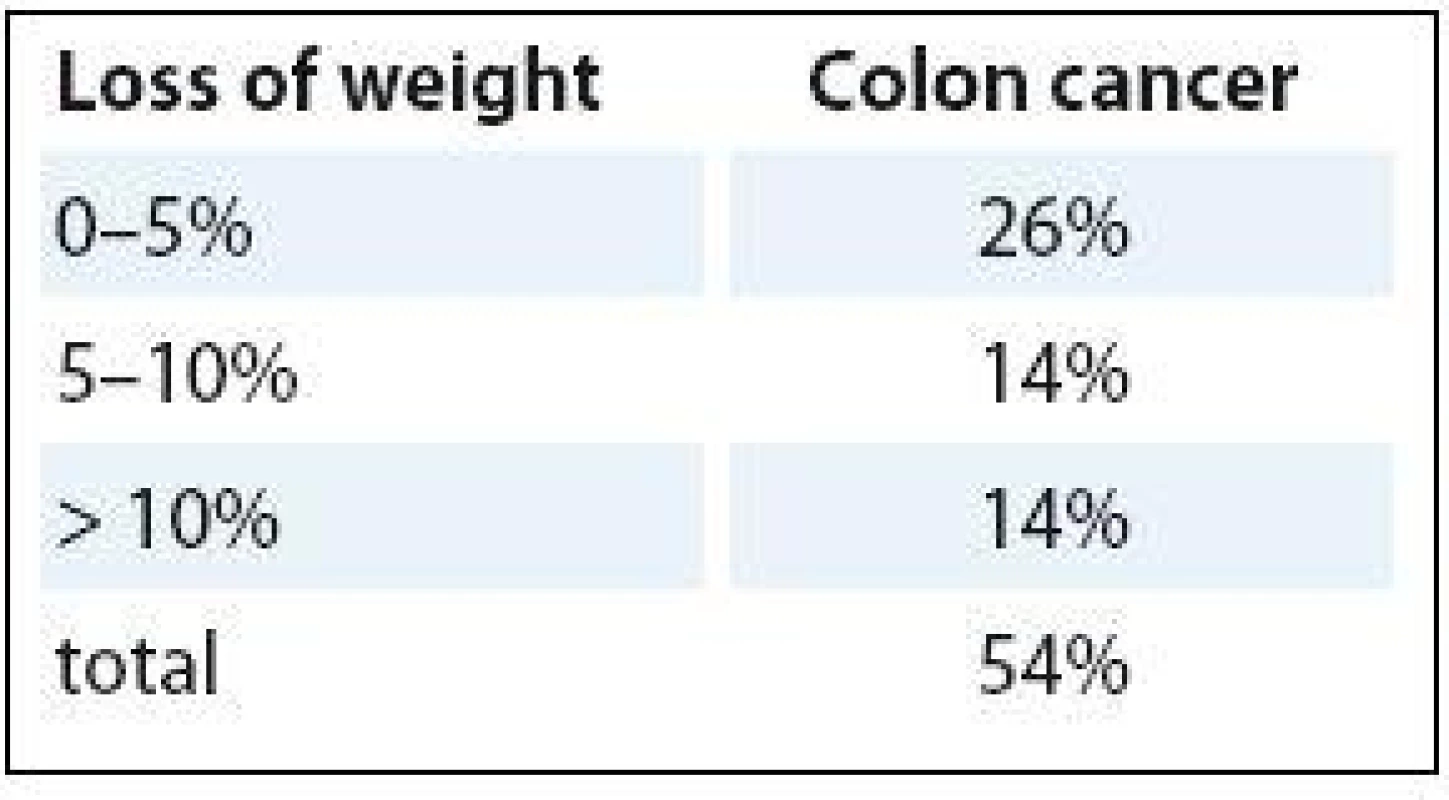

CRC prognosis is dependent on many factors, such as disease stage, age, genetic changes in tumor cells, type of treatment and response to it. The efficacy of anticancer therapy is regularly evaluated using the following indicators – objective response rate, progression-free survival and OS. Change in the tumor burden extent is assessed by the cumulative change in the size of target tumor lesions using imaging methods; WHO and RECIST criteria are most frequently used [5]. Increasingly, it is being recognized that nutritional status is also associated with important disease and treatment related outcomes in CRC, such as mortality, postoperative complications and health related quality of life. Patients with CRC undergoing surgery at nutritional risk have a higher chance of postoperative complications [6,7] and higher mortality rate [7]. Therefore, nutritional support is often used in addition to standard cancer care (chemo-/radiotherapy or surgery), not directly aimed at curing patients, but to improve both the clinical and economic outcomes of cancer management. Prevalence of malnutrition in cancer has been estimated to range from 9% (urological cancer) to 85% (pancreatic cancer) [8] with CRC having a prevalence of 30–60% [9,10]. Within this range, the landmark ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) study showed that 50% of colon cancer patients experienced some level of weight loss (Tab. 1) [11].

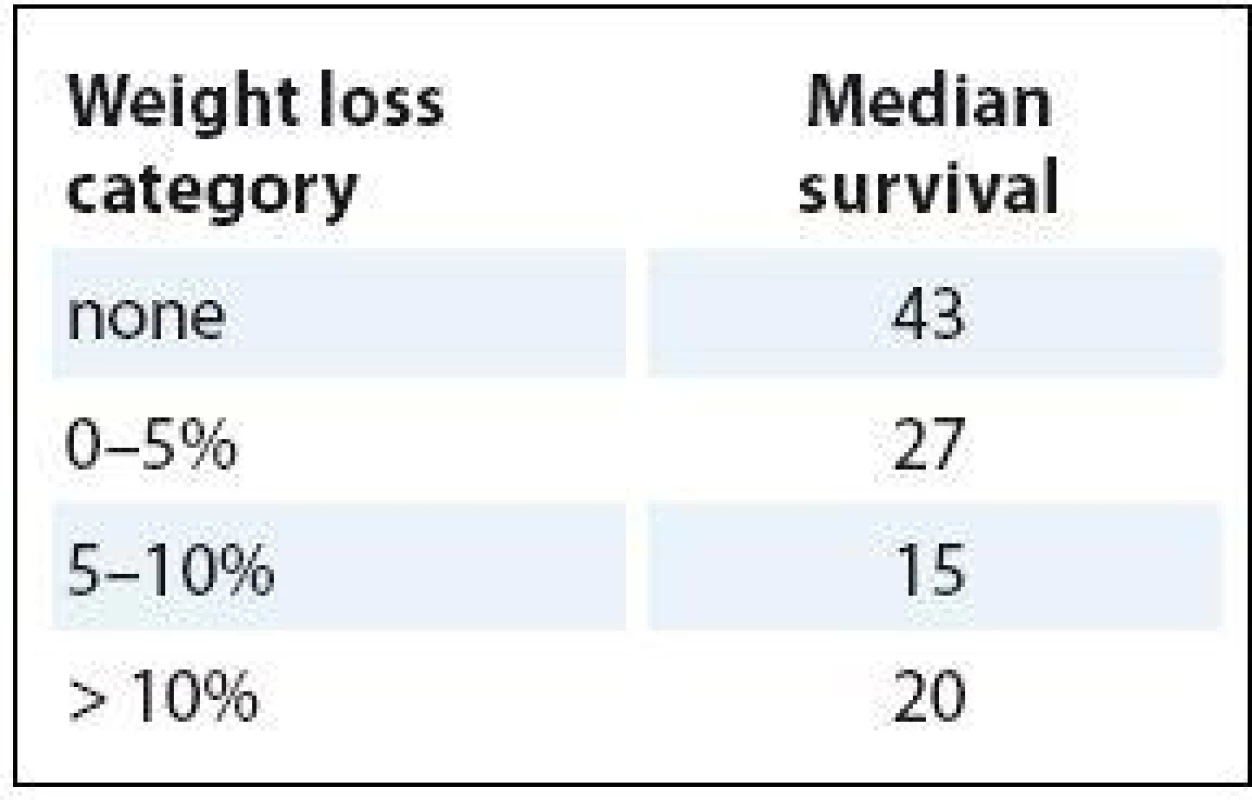

The presence of pre-chemotherapy weight loss significantly reduced median survival in colon cancer, by as much as 50% for advanced colon cancer (43 vs. 20 weeks median OS) (Tab. 2) [11].

2. Loss of weight and survival.

There are sufficient data supporting the positive impact of ONS on clinical outcomes of cancer patients who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition [11,12]. However, there is still a lack of clear guidelines on use and recommended length of use of ONS in non-malnourished patients in specific types of cancer. A study conducted by Kabata et al. [13] is a valuable source of information on preoperative use of high protein ONS in cancer patients eligible to surgery without signs of malnutrition. A reduction of frequency (from 35.4% to 14.8%) and severity of postoperative complications have been observed after two weeks supplementation of ONS in a mixed population of cancer patients (e. g. stomach, rectum, colon, ovaries etc.). To our best knowledge, there has been no study specifically done on CRC patients. In light of the current limited evidence on the effects of high protein ONS on clinical outcomes of non-malnourished CRC patients, this study was designed to assess the impact of ONS for this specific group of patients, independent of nutritional status, during the pre - and postoperative period. The reason why CRC was chosen as the subject for the study was the high disease burden of CRC and the associated costs in the Czech Republic. Special attention was paid to costs connected to hospitalization and occurrence of complications borne by payer/health insurance.

Materials and methods

This multi-centered study was conducted in three oncological centers in the Czech Republic (Nový Jičín, Ostrava, Vítkovice). The data from the study group were gathered prospectively (2012) and from the control group retrospectively (2010–2011). The study population was comprised of adult CRC patients without distant metastasis, undergoing surgery. Fifty-two patients (mean age 64) were recruited to the study group and 105 patients to the control group. All these patients signed informed consent.

Based on Working Group of Nutritional Care in Oncology within the Czech Society for Oncology (Pracovní skupina nutriční péče v onkologii při ČOS – PSNPO) recommendations, exclusion criteria were: major renal/hepatic impairments, diabetes and failure to cooperate.

The study group was instructed to take high protein ONS (Nutridrink Protein containing 20 g of protein) twice per day in addition to their standard diet for at least 10 days before and two weeks after the surgery (between the meals). Patients could choose the flavor of Nutridrink Protein according to their taste preferences. Twenty bottles were given to patients preoperatively and 28 bottles for the postoperative period. The control group was on a standard diet. The primary objective of the study was to assess the impact of pre - and post-operative nutritional support on the frequency of complications, irrespective of the initial nutritional status. Post-operative complications, such as wound and anastomosis dehiscence and infections were monitored in the centers for 2–4 weeks after surgery. The frequency of rehospitalization in the six months following surgery was also recorded.

The secondary objective was to compare the cost of treatment and length of stay for patients taking high protein ONS vs. patients on standard diet. The cost data have been provided by the health insurance company Revírní bratrská pokladna Health Insurance Company. The time horizon for economic analysis was six months.

The nutritional status was measured using the PSNPO screening protocol, created by the PSNPO, 2–4 weeks before surgery. The total score consisted of a sum of four risk factors – weight loss, BMI, food intake and a risk diagnosis (1 – lowest risk, 4 – highest risk). Infor-mation about body weight at six months before surgery was filled in by patients. Patients were interviewed to check their body mass four weeks after surgery.

Statistics

The data are provided as mean and standard deviation (e. g. weight loss, body mass index – BMI). A chi-square test has been used to compare the study population and control group. Weight loss and BMI before and after surgery have been compared using a paired t-test. The relation between BMI and pre - and postoperative use of high protein ONS was assessed by a Spearman‘s rank correlation coefficient. A correlation assessment of complications between pre - and postoperative use of high protein ONS was not possible due to an insufficient number of complications. A Fisher’s exact test was used to compare discrete variables (wound and anastomosis dehiscence, infections, the frequency of rehospitalization). A Mann-Whitney test was used for comparison of the cost data between the study and control group.

Results

Fifty-two patients were enrolled in this study. Patients in the study group were in different stages of CRC – seven patients in stage I, 14 in stage II, 24 in stage III, seven in stage IV, resp. Twenty-one patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy and 33 received adjuvant therapy after surgery. In general, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy demonstrate better treatment results than adjuvant chemoradiotherapy [14]. The average age of patients was 64 years (s.d. 9.9 year).

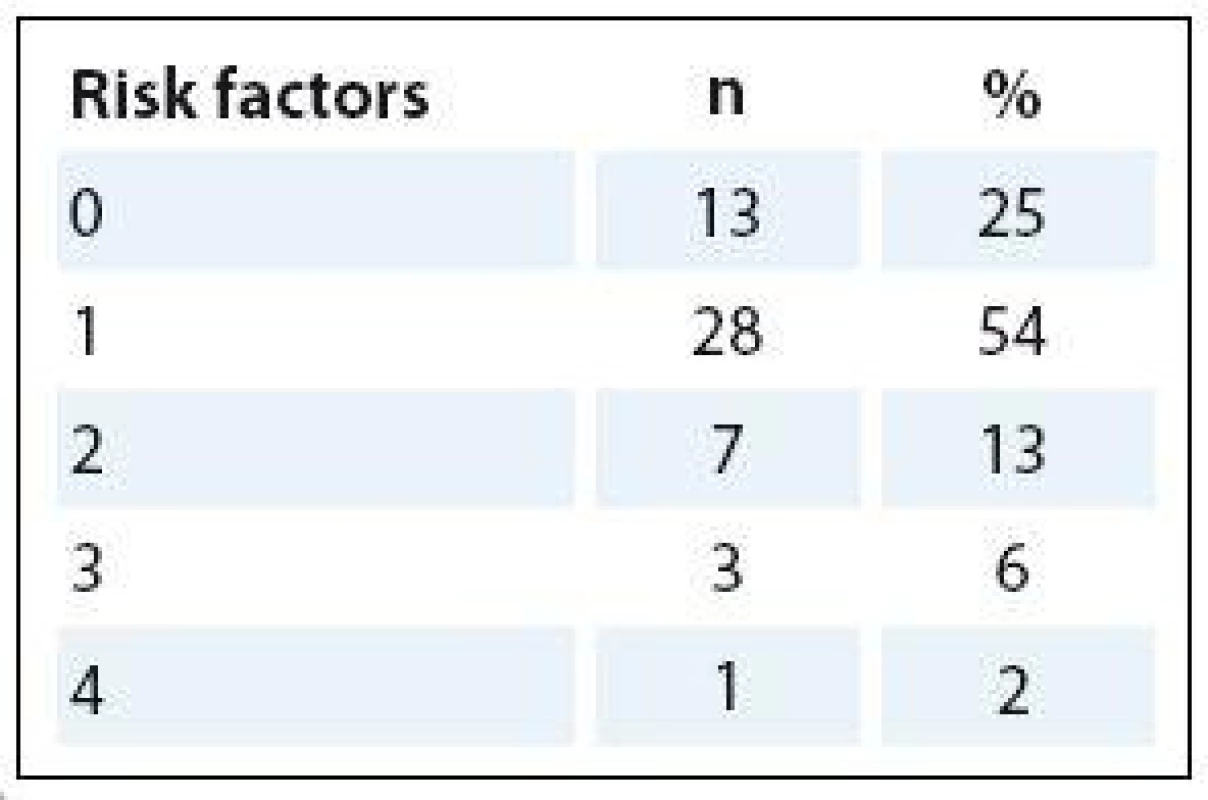

Twenty-five percent of patients were not malnourished, 67.3% were at risk of malnutrition and 7.7% were malnourished (Tab. 3). Almost 80% of patients in SG had none or one risk factor for malnutrition (weight loss, BMI, food intake, risk diagnosis).

Due to the retrospective nature of the control group, comparative data are available only for the frequency of complications, rehospitalization, length of stay and related costs. Nutritional status, compliance and patients’ preferences were only assessed for the study group.

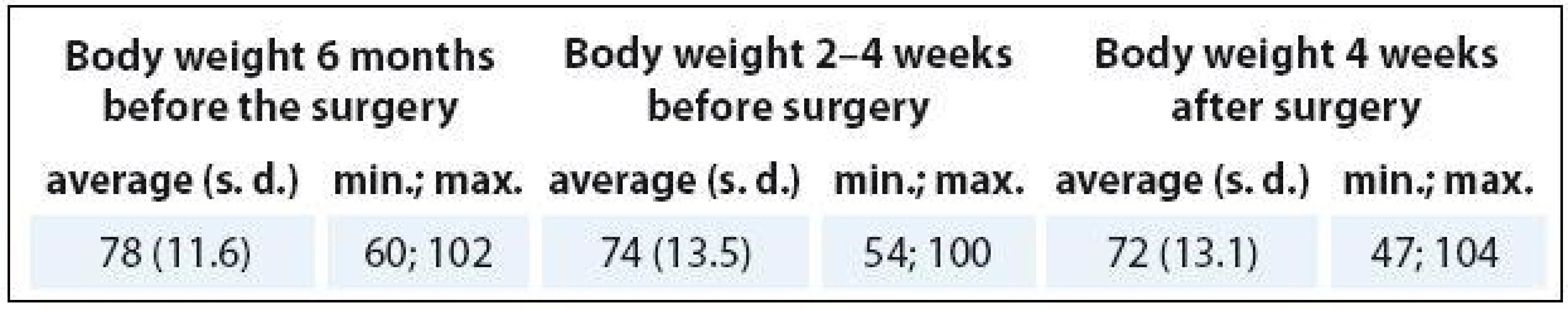

Two point 7% decrease of the average body mass was observed four weeks after surgery (Tab. 4). It is a smaller decrease in weight when compared to patients who are not commonly instructed to take high protein ONS as it is regularly reported in practice, but specific data from studies are lacking.

4. Body weight before and after surgery.

A decrease in mean BMI (25.4–24.5; p = 0.014) and a reduction in the level of weight loss (from 6.4% to 2.6% before and after surgery, not statistically significant p = 0.055) was observed after surgery.

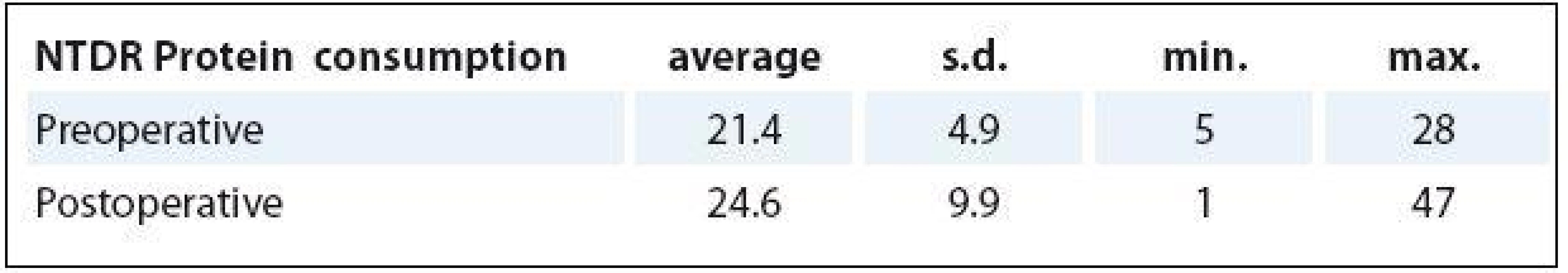

Special attention was paid to compliance of using the oral nutritional support. Sixty-nine percent of patients (n = 36) followed the instructed use of two bottles of ONS per day (400 ml/40 g protein), 25% of patients (n = 13) had used at least one bottle daily (200 ml/20 g protein), 6% (n = 3) took ONS irregularly. Before and after surgery, the average total consumption was 21.4 bottles (428 g protein) and 24.6 bottles (492 g protein), resp. As it is shown below (Tab. 5), the number of consumed bottles differs per patient and a greater number of bottles was consumed in the postoperative period.

5. The compliance of using the oral nutritional support.

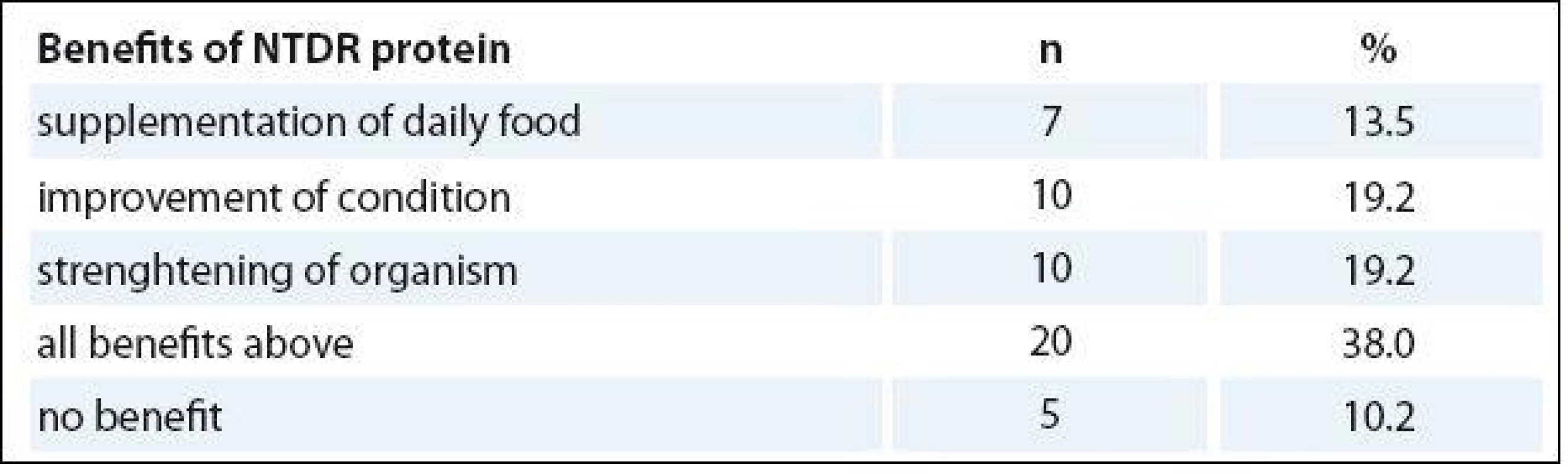

Forty-seven patients (89.8%) apprais - ed the benefits of ONS (Tab. 6).

6. The evaluation of the oral nutritional support by patients.

Postoperative complications

The frequency of postoperative complications varied in individual subjects (in many cases patients experienced two or more complications). When compared to the control group, the study population showed a 2.2 times lower relative occurrence of wound dehiscence, a 4.3 times lower relative occurrence of anastomosis dehiscence, a 2.0 times lower relative occurrence of wound infection and a 1.7 times lower relative risk of rehospitalization (Graph 1).

Graph 1. Relative risk of postoperative complications (%).

The mean LoS in the SG was 9.4 ± ± 5.0 days and in CG 12 ± 6.4 days (p = 0.002) (Graph 2). As well as the duration of hospital stays, the intensity of care while the patients were in hospital contributed to lower overall hospital costs in the SG. Mean total costs per one day in hospital were reduced by 11% in SG compared to CG, reflecting the lower complication rates in the SG. Mean total costs per one day in hospital for the SG were 479 EUR (median 462 EUR), compared to CG mean total costs 538 EUR (median 549 EUR), generating savings of 59 EUR per patient on average daily hospitalization costs.

Graph 2. Lenght of stay in hospital (LoS in days, median).

The risk of complications was decreased in SG for both malnourished and non-malnourished patients. This supports the findings of previous research (Kabata) that ONS may be beneficial for all CRC patients undergoing surgery regardless of initial nutritional status.

Six-month treatment costs

The secondary objective of the study was to perform a cost analysis of ONS by comparing costs during hospital stay and six months after hospitalization between the study group and the control group. The costs of interventions, medicines/antibiotics and equipment and material costs were taken into account. Costs connected to anti-cancer treatment e. g. chemotherapy or radiotherapy were not included.

As seen in Graph 3, during the hospital stay, there was a decline in the consumption of drugs including antibiotics, lower equipment (medical device) and material costs and less need for medical intervention in SG.

Graph 3. Costs (EUR) during hospitalisation (median).

Intervention costs were significantly lower in the ONS group (2,595 EUR in SG vs. 3,158 EUR in CG) as well as costs of medical equipment and materials (1,169 EUR in SG vs. 2,037.4 EUR in CG; p = 0.005). Medicine costs (10 vs. 66.6 EUR) and costs of antibiotic use (10 vs. 48 EUR; p <0.001) in the ONS group were significantly lower.

In order to assess long-term benefits of nutritional support, cumulative costs were also calculated during six months after surgery (Graph 4). There were significantly lower costs in the study group on procedures (3,375 EUR in SG vs. 4,110.2 EUR in CG; p < 0.001) and on medical equipment and materials (1,394 EUR in SG vs. 2,125.4 EUR in CG; p = 0.005). Costs of drugs (SG 44 vs. CG 126.8 EUR) and antibiotics (SG 10.2 vs. CG 55.7 EUR; p < 0.001) in the study group were significantly lower than in the CG.

Graph 4. Costs (EUR) 180 days after hospitalisation admission (median).

All measured costs were significantly lower in the study group vs control group. ONS generated significant savings on total costs in period of 180 days after hospital admission of 2,940 EUR per patient on average.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that significant improvements in the management of CRC surgery may be possible through the use of oral nutritional support in patients before and after surgery, independent of their nutritional status.

As healthcare systems struggle with the increasing costs of cancer care, the economic impact demonstrated in this study is highly relevant. Savings of healthcare costs of 2,940 EUR per patient opens opportunities to reinvest in managing more patients, or in allowing savings to be made in healthcare budgets. While this exact figure is only applicable in the Czech context, the impact of the reduction in complications and rehospitalizations would translate to savings in other countries as well.

During the study, only four types of complications were assessed but other complications of malnutrition are often masked as separate diseases not connected with malnutrition (e. g. pneumonia, loss of mobility, heart failure, repeated infections, bedsores, dementia, non-healing wounds, embolism, etc). This can lead to underestimating the costs and cost-effectiveness.

The retrospective nature of the control group led to some data attributes which could not be compared between groups. This ‘before and after’ study design, while lacking the internal consistency of a randomized clinical trial, can be difficult to interpret where small differences are found between groups. It is likely that general quality improvements can lead to a downward trajectory of length of stay and improvement in complication frequency. In this study, however, hospital LoS was reduced by 22%, wound infections by 50%, wound dehiscence by 56%, anastomosis dehiscence by 77% and risk of rehospitalization by 40%. These are far greater reductions than would be expected through natural improvement alone.

Following the completion of this study, these results have been recognized by the Czech Oncological Society and have been used to implement changes to the clinical practice. The use of high protein ONS in perioperative period has been increased, and greater emphasis has been put on early nutrition intervention.

The use of high protein ONS in CRC patients during the perioperative period reduces occurrence of postoperative complications, LoS and significantly reduces costs of treatment during hospitalization and six months after colorectal surgery, regardless of initial nutritional status. Perioperative nutri - tional support is beneficial and should be routinely used in malnourished patients as well as in patients with no clinical signs of malnutrition. High protein ONS reduces the number and severity of post - operative complications, especially of anastomosis dehiscence and leakage.

Early screening and intervention prior to the development of malnutrition is essential as it is easier to maintain patients in a good nutritional status than to correct a state of malnutrition, which is very often not recognized. A truly comprehensive anti-cancer strategy is not complete without an adequate nutritional intervention.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE recommendation for biomedical papers.

MUDr. Viktor Manasek

Department of Oncology Complex Oncological Center Nový Jičín

Hospital Nový Jičín, a. s.

Purkyňova 2138/16

741 01 Nový Jičín

Czech Republic

e-mail: viktor.manasek@nnj.agel.cz

Submitted: 6. 3. 2016

Accepted: 5. 5. 2016

Sources

1. Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulenat J. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer 2013; 49(6): 1374 – 1403. doi: 10.1016/ j.ejca.2012.12.027.

2. OECD. Health at a Glance: Europe 2012. Paris: OECD Publish ing 2012.

3. Dusek L, Muzik J, Maluskova D et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in the Czech Republic. Klin Onkol 2014; 27(6): 406 – 423. doi: 10.14735/ amko2014 406.

4. Cancer.org [online]. American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer. Available from: http:/ / www.cancer.org/ cancer/ colonandrectumcancer/ detailedguide/ colorectal-cancer-survival-rates.

5. Holubec L, Liska V, Finek J. The importance of early tumor shrinkage and deepness of response in as ses s ing the efficacy of systemic anticancer treatment with metastatic colorectal cancer. Klin Onkol 2015; 28(2): 89 – 93. doi: 10.14735/ amko201589.

6. Kwag SJ, Kim JG, Kang WK. The nutritional risk is a independent factor for postoperative morbidity in surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res 2014; 86(4): 206 – 211. doi: 10.4174/ astr.2014.86.4.206.

7. Schwegler I, von Holzen A, Gutzwil ler JP et al. Nutritional risk is a clinical predictor of postoperative mortality and morbidity in surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2010; 97(1): 92 – 97. doi: 10.1002/ bjs. 6805.

8. Bozzetti F, Migliavacca S, Scotti A et al. Impact of cancer, type, site, stage and treatment on the nutritional status of patients. Ann Surg 1982; 196(2): 170 – 179.

9. Stratton RJ, Green CJ, Elia M. Disease-related malnutrition: an evidence-based approach. Wal lingford: CAB International 2003.

10. Lopes JP, de Castro Cardoso Pereira PM, dos Reis Baltazar Vicente AF et al. Nutritional status assessment in colorectal cancer patients. Nutr Hosp 2013; 28(2): 412 – 418. doi: 10.3305/ nh.2013.28.2.6173.

11. Dewys WD, Begg C, Lavin PT et al. Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Med 1980; 69(4): 491 – 497.

12. Faber J, Berkhout M, Fiedler U et al. Rapid EPA and DHA incorporation and reduced PGE2 levels after one week intervention with a medical food in cancer patients receiving radiotherapy a randomized trial. Clin Nutr 2013; 32(3): 338 – 345. doi: 10.1016/ j.clnu.2012.09.009.

13. Kabata P, Jastrzębski T, Kąkol M et al. Preoperative nutritional support in cancer patients with no clinical signs of malnutrition – prospective randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 2015; 23(2): 365 – 370. doi: 10.1007/ s00520-014-2363-4.

14. Richter I, Dvořák J, Bartoš J. The combination of noadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in the treatment of rectal adenocarcinoma. Klin Onkol 2014; 27(3):166 – 172. doi: 10.14735/ amko2014166.

Labels

Paediatric clinical oncology Surgery Clinical oncology

Article was published inClinical Oncology

2016 Issue 5-

All articles in this issue

- The Importance of MITF Signaling Pathway in the Regulation of Proliferation and Invasiveness of Malignant Melanoma

- Expression of ATP-binding Cassette Proteins Pgp, MRP1, and MRP3 in Malignant and Benign Ovarian Lesions

- Multimodal Therapy of Recurrent Malignant Schwannoma

- Hyperthermic Isolated Limb Perfusion Combined with Tasonermin – a Perfusion Leakage Monitoring Technique

- Glycine-N-methyltransferase and Malignant Diseases of the Prostate

- Prognostic and Predictive Factors for Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma

- Treatment of Relapsed and Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma – Recommendations of the Czech Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group

- The Impact of High Protein Nutritional Support on Clinical Outcomes and Treatment Costs of Patients with Colorectal Cancer

- Malignant Mesothelioma of the Tunica Vaginalis Testis. A Clinicopathologic Analysis of Two Cases with a Review of the Literature

- Sentinel Lymph Node in Thin and Thick Melanoma

- Clinical Oncology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- The Impact of High Protein Nutritional Support on Clinical Outcomes and Treatment Costs of Patients with Colorectal Cancer

- Treatment of Relapsed and Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma – Recommendations of the Czech Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group

- Multimodal Therapy of Recurrent Malignant Schwannoma

- Malignant Mesothelioma of the Tunica Vaginalis Testis. A Clinicopathologic Analysis of Two Cases with a Review of the Literature

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career