-

Medical journals

- Career

Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap on extremity defects – case series

Authors: Bajus A.; Streit L.

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Plastic and Aesthetic Surgery, St. Anne's University Hospital Brno and Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

Published in: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 64, 1, 2022, pp. 39-43

doi: https://doi.org/10.48095/ccachp202239Introduction

Reconstruction of larger upper and lower extremity trauma or tumor resection defects can be challenging. Free tissue transfer has become the workhorse for larger and more distal defects, and proper selection of the optimal flap regarding the size, pedicle length, or donor-site morbidity becomes increasingly important. Especially in distal parts, relatively thin flaps are needed not to interfere with the function or aesthetic appearance of the extremity. The superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator (SCIP) flap has been shown as a powerful but still not so commonly used, tool for this kind of reconstruction.

The SCIP [skip] flap was firstly described by Koshima in 2004 [1]. The flap is nourished by superficial (medial) or deep (lateral) superficial circumflex iliac artery (SCIA) branch (perforator) with pedicle length of 5–6 cm and vessels diameter of 0,8–1,8 mm [2,3]. When elevated in the level of superficial fascia, SCIP flap can be as thin as 3–12mm and flaps with the surface up to 35 x 12 cm are reported [4,5]. As a chimeric flap, SCIP flap can be harvested containing external oblique muscle fascia [6], sartorius muscle [7], iliac bone [8], or lymph nodes [9].

The pliability of the groin skin, its thinness, and minimal donor-site morbidity with concealed scar make the SCIP flap an important reconstructive option for soft-tissue coverage of extremity defects, especially in cases when a long pedicle is not needed. Currently, the vast majority of publications concerning the SCIP flap come from Asia, and publications from other parts of the world are still relatively rare [10,11]. In consequence, we have decided to share as a case series our first experience on the use of SCIP flap as applied to extremities.

Case demonstrations

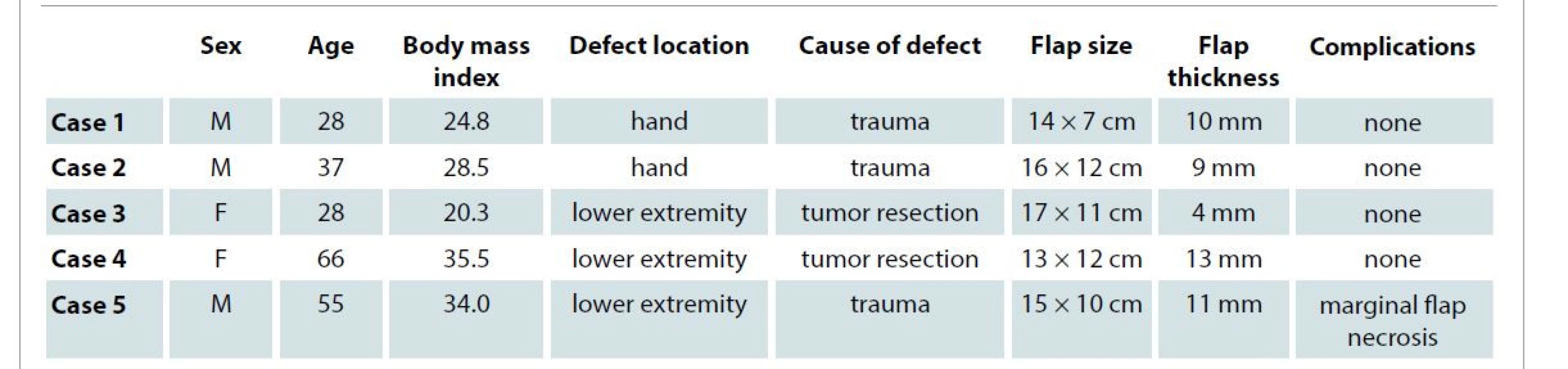

Between January and June 2021, a retrospective review of the five patients (three men and two women) who underwent defect coverage of an upper or lower extremity with a SCIP flap was performed at our department. The mean age of the patients was 43 years (28–67 years). Their body mass index (BMI) was 28.6 on average. Two patients suffered from upper extremity defects, three patients from lower extremity defects. Three defects were caused by trauma (cases No. 1, 4, and 5) and two by tumor resection (cases No. 2 and 3). All flaps were preoperatively planed with the use of colour duplex ultrasound. The course of the superficial (medial) and deep (lateral) SCIA branch and the superficial circumflex iliac vein (SCIV) with their emergence points at the level of the superficial fascia were marked on every patient’s skin. The size and shape of the flap were designed according to the shape of the defect. When a longer pedicle was needed (cases No. 2 and 4), the deep branch was preferably selected. Otherwise, the superficial branch was used because of its easier dissection. The dissection started on the lateral aspect of the flap and proceeded medially in the level of the superficial fascia. When the emergence points of the vessels of the pedicle were approached, the dissection continued through the superficial fascia until the branching (usually from femoral artery and great saphenous vein) occurred. On average, the thickness of elevated flaps was 9.4 mm. Demographic data and SCIP flap characteristics are shown in Tab. 1.

1. Patients and superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flaps characteristics.

F – female, M – male We experienced no total flap loss and none of the flaps has required revision surgery for neither ischemia nor congestion. One of the patients developed marginal flap necrosis which was treated by necrectomy and direct skin closure. Individual cases are listed by the type of defects. None of the patients developed donor-site lymphedema.

Hand defects

Case 1

A 28-year-old man suffered a laceration of the 2nd and 3rd ray of his left hand by a press. The replantation was not possible due to excessive damage of amputated parts. After debridement, a silicon spacer was placed inside the wound to preserve space for future replacement of missing metacarpal bones [12]. Subsequently, the defect was covered by a SCIP flap which was flipped around the silicon spacer. The 14 x 7 cm SCIP flap was elevated in the level of superficial fascia. The radial artery and cephalic vein were used as recipient vessels. The temporary silicone spacer was replaced with an iliac bone graft seven months later. At an 11-month follow-up, the patient showed good contour of the hand, and he is in the decision-making process to undergo a toe-to-hand transfer (Fig. 1A–C).

Fig. 1 (case 1). A) Hand injured by press. B) A silicon spacer maintains space for future bone grafting. C) Eleven months after reconstruction with a superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap.

Case 2

A 37-year-old COVID-19 positive man suffered a subtotal multi-level amputation of his left thumb and hypothenar. The injury was caused by a circular saw. After 5 days, despite replantation, the patient developed wound infection (Bacillus sp., Pantoea agglomerans) leading to necrosis of thenar skin, muscles, first metacarpal bone, and proximal half of proximal phalanx. After controlling the infection (ciprofloxacin, metronidazole) and necrotic tissue debridement, the remaining bones of the thumb were stabilized by external fixation and the defect was covered with a SCIP flap (16 x 12 cm) elevated in the level of superficial fascia. The radial artery and cephalic vein were used as recipient vessels. The missing metacarpal bone was replaced by an iliac bone graft three months later. The patient at the 9-month follow-up showed good contour of the hand and he is currently scheduled for extensor and flexor tendons reconstructions (Fig. 2A, B).

Fig. 2 (case 2). A) Hand defect after debridement. B) Nine months after reconstruction with a superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap and iliac bone grafting.

Lower limb defects

Case 3

A 28-year-old woman with a history of type I diabetes developed a Marjolin ulcer in a burn scar on the lateral surface of the distal third of her right leg. She underwent a radical tumor and burn-scar resection, and the defect was covered by a free 17 x 11 cm SCIP flap elevated in the level of superficial fascia. Anterior tibial vessels were used as recipient vessels. On postoperative day 5, early compression of the flap and extremity with the elastic bandage was started as well as early ambulation. Since postoperative day 14, the patient is wearing a compression garment and her ambulation is without any limitation. At a 7-month follow-up, the patient is without any signs of tumor recurrence, and the leg shows a nice contour (Fig. 3A, B).

Fig. 3 (case 3). A) Burn scar with Marjoline tumor above the lateral malleolus. B,C) Seven months after the tumor and burned scar resection and superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap coverage.

Case 4

Two years ago, a 66-year-old woman with a history of non-differentiated sarcoma G3 of her left tibia underwent tumor removal with resection of a third of her tibial bone circumference. The bone was replaced by a bone cement filling and the soft-tissue defect was covered with skin-grafted serratus anterior free flap. Postoperatively, the patient underwent radiation therapy (50 + 20 Gy). After 15 months, a stress fracture of the cement-filled tibia occurred, and irradiated bone fragments were not healing. The patient was treated by re-elevating the original serratus anterior flap and cement-filling removal. Osteosynthesis was performed by intramedullary nailing combined with a free fibula flap transferred from the patient’s right side. Accidentally, the pedicle of the original serratus anterior flap was damaged during the dissection, and gradually the flap almost completely succumbed to necrosis. After necrectomy and removal of free fibula skin island marker, the soft tissue defect was finally covered by a SCIP flap elevated in the level of superficial fascia. Anterior tibial vessels were used as recipients. On postoperative day 5, early compression of the flap and extremity was started, and since postoperative day 10 the patient has been gradually ambulating on crutches. Despite our recommendations, compression garment has begun to be used 5 months after the procedure. Before that, due to poor patient compliance, obesity (BMI 35.5), and chronic venous disease the flap was oedematous. At 7 months, the vascularized fibula is healed to the tibial bone and the leg is without any signs of tumor recurrence. The patient can ambulate without crutches, which she uses only for walking longer distances. The contour of the leg is poor, but the patient is satisfied and does not desire any debulking procedure.

Case 5

A 55-year-old man suffered a cutting injury of his right leg by a dropped glass board. The anterior aspect of the middle third of his leg was amputated causing a 14 x 9 cm defect with a missing of 5 x 4 cm of the tibial periosteum. The defect was covered emergently with a SCIP flap elevated in the level of superficial fascia, and anterior tibial vessels were used as the recipient. Healing was complicated by a 7x1 cm marginal necrosis on the medial aspect of the flap which was treated by necrectomy and primary closure. On day 7 after the initial procedure, compression of the flap and extremity with the elastic bandage was started as well as ambulation. At a 5-month follow-up, the patient’s ambulation is without any limitations and the extremity has a good contour that does not interfere with its function.

Discussion

This study represents our first experience review of hand and lower-extremity reconstruction utilizing free SCIP flaps. We decided to use these flaps for coverage of medium-sized shallow defects where a long pedicle was not needed. The technique of the dissection in the level of superficial fascia has been well described by Hong [5]. Substantial advantages of SCIP flaps are versatility and minimal donor-site morbidity with a mostly concealed scar. Moreover, in all directions, very pliable groin skin makes the adaptation to various defects easier. Those are the reasons why, despite the short pedicle, the popularity of SCIP flap has been rapidly growing.

The bulkiness is an important factor to consider during the selection of a proper flap for extremity reconstructions. Maintaining the contour that does not interfere with the function is essential not only on hands but also on lower extremities. Also, an aesthetic consideration should not be of secondary concern but should be a part of the reconstructive algorithm. More than 20% of patients undergoing lower-extremity free-flap reconstruction desire secondary revisions following the initial procedure. This is especially true in younger patients with distal leg and ankle reconstruction [13]. Due to the thinness of subcutaneous tissue in the area around the anterior superior iliac spine, the SCIP flap is inherently thin, especially when elevated in the level of superficial fascia (Fig. 4). This makes the SCIP flap an excellent option for reconstructions of extremities. Although two of our patients had BMI > 30, none of them needed secondary debulking of the flap. Nevertheless, we found it slightly more difficult to dissect the flap in obese patients. When thicker subcutaneous tissue was present, the superficial fascia was not as recognizable structure as it was in slimmer patients, and we found it more demanding to maintain the right plane of elevation. In that case, the use of a hand-held doppler helped control the position of SCIA during the dissection.

Fig. 4. Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap elevated in the level of superficial fascia before the ligation of the pedicled.

Due to the concern of circulation compromise, many surgeons hesitate to dangle or challenge the flap in the early postoperative phase. As prevention of edema and stabilization of the flap during ambulation, we started to apply the early compression therapy in patients undergoing reconstructions on lower extremities as described by Suh et al [14]. We only slightly adjusted the concept to our conditions by using a compression bandage instead of a compression garment during the initial days of the postoperative compression therapy.

Our experience with SCIP flap is still very limited, yet we consider the results of distal extremities reconstructions using the SCIP flap to be superior to the results using other in our department established flaps like the latissimus dorsi muscle or anterolateral thigh flap. In addition, the complication rate was minimal.

Conclusion

Our case series demonstrates the possible use of a SCIP flap in upper and lower extremities reconstruction. With its low thickness, low donor-site morbidity, and ease of harvest, we recommend SCIP flap to be considered as one of the primary reconstructive options for various extremities defects.

Roles of authors: Both authors have similarly contributed to this work.

Conflict of interest: Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors declare that this study received no financial support. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research ethical standards.

Adam Bajus, MD

Department of Plastic and Aesthetic Surgery

St. Anne's University Hospital Brno and Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University

Berkova 34

612 00 Brno

Czech Republic

e-mail: adam.bajus@seznam.cz

Submitted: 1. 12. 2021

Accepted: 16. 1. 2022

Sources

1. Koshima I., Nanba Y., Tsutsui T., et al. Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap for reconstruction of limb defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004, 113(1): 233–240.

2. Altiparmak M., Cha HG., Hong JP., et al. Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap as a workhorse flap: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2020, 36(8): 600–605.

3. Hsu WM., Chao WN., Yang C., et al. Evolution of the free groin flap: the superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007, 119(5): 1491–1498.

4. Hong JP., Choi DH., Suh H., et al. A new plane of elevation: the superficial fascial plane for perforator flap elevation. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2014, 30(7): 491–496.

5. Hong JP. The superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap in lower extremity reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 2021; 48(2): 225–233.

6. Sumiya R., Tsukuura R., Mihara F., et al. Free superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator fascial flap for reconstruction of upper abdominal wall with extensive infected herniation: a case report. Microsurgery. 2021, 41(3): 270–275.

7. Yamamoto T., Saito T., Ishiura R., et al. Quadruple-component superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator (SCIP) flap: a chimeric SCIP flap for complex ankle reconstruction of an exposed artificial joint after total ankle arthroplasty. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016, 69(9): 1260–1265.

8. Iida T., Narushima M., Yoshimatsu H., et al. A free vascularised iliac bone flap based on superficial circumflex iliac perforators for head and neck reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013, 66(11): 1596–1599.

9. Lin CH., Ali R., Chen SC., et al. Vascularized groin lymph node transfer using the wrist as a recipient site for management of postmastectomy upper extremity lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009, 123(4): 1265–1275.

10. Zubler C., Haberthür D., Hlushchuk R., et al. The anatomical reliability of the superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator (SCIP) flap. Ann Anat. 2021, 234 : 151624.

11. Kueckelhaus M., Gebur N., Kampshoff D., et al. Initial experience with the superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator (SCIP) flap for extremity reconstruction in Caucasians. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2022, 75(1): 118–124.

12. Streit L., Mrázek T., Veselý J. Dorsoradial forearm flap with silicone bone spacer in reconstruction of A combined THUMB injury – case report. Acta Chir Plast. 2015, 57(3–4): 75–78.

13. Nelson JA., Fischer JP., Haddock NT., et al. Striving for normalcy after lower extremity reconstruction with free tissue: the role of secondary esthetic refinements. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2016, 32(2): 101–108.

14. Suh HP., Jeong HH., Hong JPJ. Is early compression therapy after perforator flap safe and reliable? J Reconstr Microsurg. 2019, 35(5): 354–361.

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine Traumatology

Article was published inActa chirurgiae plasticae

2022 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- Depression and anxiety disorders in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome after surgery – a case control study

- Recurrence of breast ptosis after mastopexy – a prospective pilot study

- Development of a questionnaire for a patient-reported outcome after nasal reconstruction

- Breast reconstruction with autologous abdomen-based free flap with prior abdominal liposuction – a case-based review

- Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap on extremity defects – case series

- Emergency evacuation low-pressure suction for the management of extravasation injuries – a case report

- Editorial

- Efficacy of pedicled anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of regional defects – a record analysis

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap on extremity defects – case series

- Efficacy of pedicled anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of regional defects – a record analysis

- Recurrence of breast ptosis after mastopexy – a prospective pilot study

- Breast reconstruction with autologous abdomen-based free flap with prior abdominal liposuction – a case-based review

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career