-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Two-stage surgical treatment of inferior vena cava traumatic rupture including urgent transport to a specialized unit

Traumatická ruptura dolní duté žíly s odloženým ošetřením po překladu na specializované pracoviště

Traumata dolní duté žíly stejně jako velká poranění jater jsou stále velkou výzvou pro ošetřující tým i pacienta. Nejobávanější hrozbou je život ohrožující krvácení. Prezentujeme případ polytraumatizovaného muže (Injury Severity Score 35) s rupturou juxtahepatické porce dolní duté žíly, kterého jsme úspěšně ošetřili ve dvou dobách. První operace se uskutečnila v krajském traumacentru a řídila se zásadami damage-control operativy. Po stabilizaci byl pacient k definitivnímu ošetření letecky transportován na kliniku se specializací na hepatopankreatobiliární a transplantační chirurgii. Vzhledem k tomu, že rozsah poranění dolní duté žíly nebyl před druhou operací přesně znám, operaci asistoval také kardiochirurgický tým. Domníváme se, že zkušenosti s transplantací jater a s ní spojené chirurgické postupy jsou pro tyto situace užitečné.

Klíčová slova:

játra – dolní dutá žíla – trauma – transport – odložené ošetření

Authors: J. Kristek 1; P. Hromádka 2; M. Konarik 3; J. Froněk 1

Authors place of work: Department of Transplant Surgery, Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Prague Head of Department: Assoc. Prof. J. Fronek, M. D., Ph. D., FRCS 1; Center of Surgery, Regional Hospital, Liberec Head of Department: P. Hromadka, M. D. 2; Department of Cardiovascular and Transplant Surgery, Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Prague Head of Department: Prof. J. Pirk, M. D. 3

Published in the journal: Rozhl. Chir., 2017, roč. 96, č. 4, s. 168-173.

Category: Kazuistiky

Summary

Inferior vena cava injury as well as major liver injury remains a formidable treatment challenge. The most imminent danger is life-threatening bleeding. In this report, we present a case of polytrauma (Injury Severity Score 35) with arupture of the juxtahepatic inferior vena cava which was successfully treated using two-stage approach. The first part of the treatment consisted of damage control laparotomy at a level I trauma center. After stabilization, the patient was air-transported to receive the definitive treatment at a tertiary care facility experienced in hepatopancreatobiliary and transplantation surgery. As the level of injury was not clear prior to the second stage surgery, a cardiac team also assisted the operation. The second stage procedure was uneventful. The patient is doing well and is preparing to return to work. We believe that experience with major abdominal, thoracic and liver transplantation surgery is beneficial in such cases.

Key words:

liver – inferior vena cava – trauma – transport – two-stage surgeryIntroduction

The term liver injury comprises a broad spectrum of lesions. They range from relatively benign superficial lacerations and subcapsular hematomas to the most serious juxtahepatic venous lacerations and liver avulsion. These injuries are graded according to The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma-Organ Injury Scale (AAST-OIS, [1]). Injuries to the hepatic veins or the juxtahepatic vena cava are graded V according to AAST-OIS. The greatest priority in the management of patients with a rupture of the inferior vena cava (IVC) is to arrest the hemorrhage. Depending on the specific series, the mortality of patients with this type of injury ranges from 13 to 100%, with an average of 65% for blunt traumas and 33% for penetrating ones [2–9, Tab. 1]. Exsanguination is the overwhelming cause of death [10]. The following citations illustrate briefly the desperate situation the surgeon may face:

Tab. 1. Etiologies and mortalities of blunt and penetrating injuries of the inferior vena cava [2] ![Etiologies and mortalities of blunt and penetrating injuries of the inferior vena cava [2]](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image/18711aab6d5f1bf9ddfc6f0395073ba3.png)

“The central features of abdominal vascular trauma: massive bleeding from inaccessible sites, multiple associated injuries, and an extremely narrow window of opportunity to save the patient. You not only see the bleeding, but you can also often hear it.” [11]

“Rupture of the liver is fortunately an accident not often met with, but one which, when it is seen, may be associated with a condition of the patient as serious as anyone can meet with in surgical practice.” [12]

Thus, rupture of the juxtahepatic inferior vena cava represents one of the most adverse situations a patient and his/her surgical team may encounter [13]. In this article, we would like to present our experience with successful two-stage surgical treatment of an inferior vena cava traumatic rupture which included urgent transport to a specialized unit.

Case report

A 34-year-old healthy male, living in a rural area, sustained a blunt thoracoabdominal trauma when he got squeezed against a wall by a bale of hay that was being transported by a tractor. Upon arrival of an emergency rescue service, he was conscious and normotensive. The patient was emergently transported by helicopter to the regional level I trauma center. At the time of arrival (65 min after announcement), the symptoms of shock were not expressed (vital signs were as follows: BP 100/60 mmHg, HR 105/min, GCS 14–15, Hb 10.7 g/dL). Since he was stable, a Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma and a CT scan was advocated revealing a diaphragmatic rupture with stomach, bowel and small intestine herniation into the left hemithorax with consequent mediastinum displacement, a massive left-sided hemoviscerothorax, and avulsion of the spleen, pancreatic tail and also left kidney (Fig. 1–4). Urgent surgery was indicated and the strategy followed the damage control principles (abbreviated laparotomy with planned re-operation after stabilization). The peritoneal cavity was entered via a vertical midline xiphoid-pubis incision. There was approximately 2.5 L of blood in the abdomen and about 0.5 L of blood in the left hemithorax. The viscera were repositioned into the abdominal cavity, the diaphragm was sutured and splenectomy, left nephrectomy and distal pancreatectomy were performed. The attempts to manage ongoing bleeding from the retrohepatic area caused massive blood loss and led to a cardiac arrest with the necessity of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (spontaneous circulation returned within 2 min). The following treatment consisted of perihepatic packing, wound closure and prompt transport to the intensive care unit (ICU) to resuscitate and stabilize the patient. In further course, digital subtraction angiography was employed with a finding of suspected laceration/avulsion of the left hepatic vein (Fig. 5). A clinic specialized in transplantation surgery was contacted and agreed to take further care of the patient. The referral took place on the first post-operative day by air transport. The patient was intubated, with minimal vasopressor support (norepinephrine 0.25 mcg/kg/min) and the transport was uneventful. After arrival, the patient underwent further resuscitation at the ICU. Abdominal cavity re-exploration took place on the very same day. The plan was to perform total vascular hepatic exclusion first and, having done so, to take care of the vascular trauma. The abdominal exploration showed a moderate amount of liquid and coagulated blood. All tissues, including the retroperitoneum, looked edematous. In the left upper quadrant, there were abdominal packings. The liver surface was decapsulated and diffusely bleeding but showed no signs of deep parenchymal lacerations. The removal of pads from the retrohepatic area immediately caused immense bleeding, which was consistent with the phlebography finding – the assumption of an extensive injury to the IVC and/or left hepatic vein. The preparation for complete hepatic vascular exclusion (the Heaney maneuver) was carried out by mobilizing the right liver from its attaching ligaments all the way to the IVC, which enabled us to encircle the infrahepatic suprarenal IVC with a Rumel tourniquet. Then, we placed a tape around the hepatoduodenal ligament (the Pringle maneuver). The cardio-surgical team extended the incision to median sternotomy and placed a tape around the supradiaphragmatic (intrapericardial) IVC (Fig. 6). They were standing by, ready to place a venovenous bypass in case of circulatory deterioration of the patient. The achievement of complete vascular liver exclusion enabled us to fully quantify the extent of the injury: the IVC had an approximately 4-cm longitudinal tear extending from the diaphragm to the left hepatic vein. It was repaired by lateral venorrhaphy using continuous polypropylene 4–0 suture (Fig. 7). This very situation did not necessitate employing the useful adjuncts to the total vascular exclusion, i.e. supraceliac aortic cross-clamping or venovenous bypass. The abdominal wall was temporarily closed using a running cutaneous suture to prevent the development of abdominal compartment syndrome and, at the same time, to return the patient to the ICU as soon as possible.

Fig. 1: A CT scan of the trunk with i.v. contrast (coronal view) shows diaphragmatic rupture with stomach (black arrow) herniating into the left hemithorax and consequent mediastinal shift (triangle). There is a left-sided hemohemithorax (black dot). Left kidney (white arrow) is not contrast-enhanced.

Fig. 2: This CT scan of the trunk demonstrates bowel herniation (black arrow) into the left hemithorax with a consequent left lung compression (white arrow).

Fig. 3: A CT scan of the abdomen with i.v. contrast (axial view) reveals the left-kidney (black arrow) which is not contrast-enhanced. The left renal artery (white arrow) is truncated.

Fig. 4: A CT scan of the thorax (axial view) demonstrates the rim of the stomach (triangle) herniated into the left hemithorax which is filled with blood. Both lungs (white arrows) are compressed and the mediastinum (black arrow) is dislocated to the right.

Fig. 5: A digital subtraction angiogram of both the IVC and the right hepatic vein. The right hepatic vein is clearly visualized (black arrow). Abdominal packing (white arrow) and skin staples (triangle) are also clearly visible. The left hepatic vein is not visualized.

Fig. 6: A peroperative view. A thoracolaparotomy incision. The Rumel tourniquets are in situ ready to be used around the hepatoduodenal ligament and the infrahepatic IVC (black arrows) and the supradiaphragmatic IVC (white arrow). If they were tightened, total hepatic vascular exclusion would be carried out. Decapsulation of the liver (triangle).

Fig. 7: Intraoperative view of the sutured defect in the IVC (black arrow). The left lateral segment of the liver is retracted (white arrow).

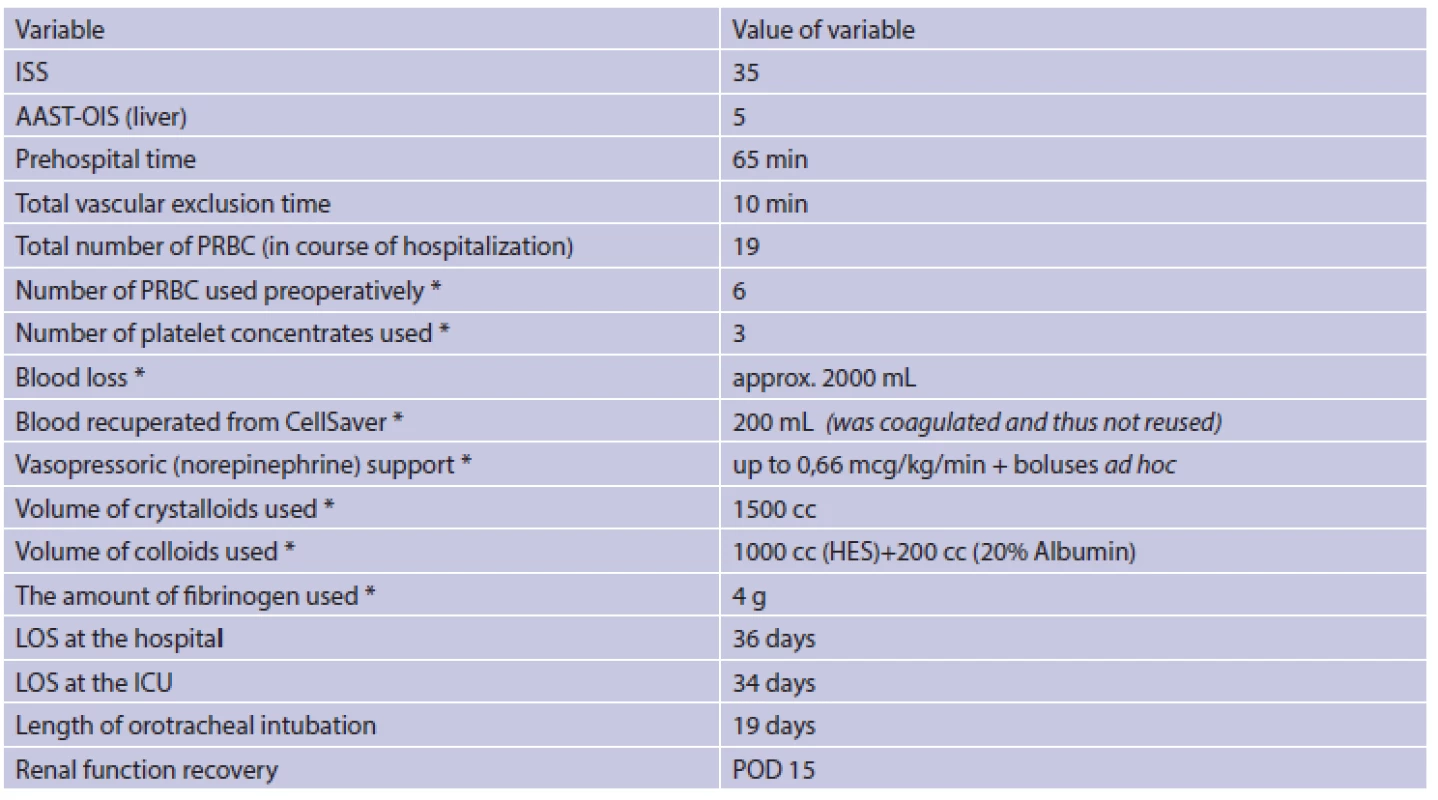

In further course, there were two more planned revisions in the operating room (on postoperative days 4 and 7) which comprised abdominal cavity exploration with peritoneal lavage, partial wound closure with negative pressure wound therapy, and subsequent complete wound closure. The postoperative period was marked by an acute renal failure that required temporary continuous venovenous hemodialysis, a pancreatic leak which was successfully treated with endoscopic stenting and drainage of the leak collection under ultrasonographic guidance, and pericardial effusion which was also successfully drained. Due to persistent fever, a few courses of antibiotic treatment were administered. Nutritional support was given parenterally and via a nasojejunal tube. The patient was discharged with renal functions fully recovered on day 36 after injury (Tab. 2). Postsplenectomy vaccination was a matter of course.

Tab. 2. Important data regarding the trauma, operation and postoperative period

Explanation: *in course of the 2nd look operation. AAST-OIS The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma-Organ Injury Scale; ISS Injury Severity Score; HES Hydroxyethyl starch; LOS length of stay; POD Postoperative Day; PRBC Packed Red Blood Cells. Currently, i.e. 10 months after injury, the patient attends outpatient physiotherapy and plans to pursue his former profession of an agricultural worker when he is fit to do so.

Discussion

This paper presents a case report of a polytrauma patient (ISS 35) with a rupture of the juxtahepatic IVC extending to the left hepatic vein (grade V liver injury according to the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma-Organ Injury Scale [1]) who was successfully treated in two stages using the damage control principles. Importantly, the definitive treatment was performed after transporting the patient to a specialized institution. In spite of continued developments in resuscitation and surgical techniques, vena caval injuries remain life-threatening injuries with dismal outcomes [13,14]. Approximately 30–50% of patients with IVC injuries die before arriving to the hospital, while more than one third of the remaining patients die within 24 hours despite all efforts [9,14]. Survival rate is directly related to the site of injury to the IVC (the closer the injury to the heart, the higher the mortality rate), the presence of significant hypotension on arrival, and the type and number of associated injuries [14]. Blunt injuries are less common but have higher mortality than penetrating ones [14,15, Tab. 1].

The introduction of damage control surgery has led to improved survival rates in severely traumatized, exsanguinating patients [16]. It is aimed at arresting bleeding and contamination, stabilizing potentially fatal problems at first look laparotomy (rapid evacuation of blood, four-quadrant packing, limiting the enteric spillage), with secondary resuscitation (rewarming, ventilatory support, coagulopathy and hemodynamics correction) followed by scheduled definitive laparotomy or series of laparotomies to provide definitive repair of injuries or physiological deficits once coagulation has returned to an acceptable level [17,18].

As cited by Stone et al. [17]: “…repair of only those vessels vital to survival, with ligation of all others; ligation of bowel ends; the spleen and kidney, if bleeding, were removed unless renal injury was bilateral; there were no drains, and no bowel or urinary stomas were created; laparotomy pads then were packed tightly into the peritoneal cavity;…”. The reason for doing so is to prevent the development of the fatal cycle of hypothermia, coagulopathy and acidosis [18]. The decision to use damage control strategy must be made before profound physiological derangements arise. Observing this principle is vital in patients with vena cava or liver rupture.

Since the re-exploration in a patient with severe liver trauma and/or IVC rupture aims at dealing with very challenging, specific injuries, it may be prudent to carry it out at an institution proficient in both liver and vascular surgery. The surgeon needs to be familiar with the variety of techniques available for exposure and repair. One of the most complex ones is total hepatic vascular exclusion [19]. As our institution is also a transplant center, its surgeons are well acquainted with organ procurement procedures that involve exposure and control of major vascular structures (the extended Kocher maneuver, the Cattell–Braasch maneuver etc.). We firmly believe that this experience was beneficial in our case. However, it needs to be emphasized that the greatest downside to the use of complete hepatic vascular isolation is the rapid and profound decrease in venous return to the heart and possible consequent cardiovascular collapse and/or cardiac arrest. If the technique is to be used, all resuscitation lines should be placed in the upper extremities or the mediastinal veins. To effectively minimize the risk of cardiovascular collapse, a venovenous bypass might well be used [20]. In the case of severe hypotension, cross-clamping of the supraceliac aorta could be a temporary solution.

It is also necessary to state that up to 90% of patients with blunt liver injuries (mostly grade I and II) are managed non-operatively [21]. In a case of contained injury with no or minimal active bleeding and no other injuries that require exploration, expectant management with serial CT scanning is a relatively safe and feasible alternative to operative management [21,22,23]. The key discriminating factor in this precarious situation is the hemodynamic stability/instability.

Conclusions

Grade III-V liver injuries and IVC ruptures are very demanding, imminently life-threatening injuries that mostly require urgent surgical revision without further delay. The first operation should follow the damage-control strategy. In this case report we describe the successful management of a patient with IVC rupture treated in this way. We advocate performing an abbreviated damage control laparotomy at a regional institution and, after stabilizing the patient, a prompt referral to a specialized care center where the whole spectrum of surgical options and intensive care support is readily available.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

AAST The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma

ACS Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

AIS Abbreviated Injury Scale

BP Blood Pressure

cc cubic centimeter

CT Computed Tomography

GCS Glasgow Coma Scale

Hb Hemoglobin

HES Hydroxyethyl starch

HR Heartrate

ICU Intensive Care Unit

ISS Injury Severity Score

IVC Inferior Vena Cava

LOS Length of Stay

OIS Organ Injury Scale

POD Postoperative Day

PRBC Packed Red Blood Cells

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have not conflict of interest in connection with the emergence of and that the article was not published in any other journal.

MUDr. Jakub Kristek

Department of Transplant Surgery

Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine

Videnska 1958/9

140 21 Prague

Czech Republic

e-mail: jakub.kristek@ikem.cz

Zdroje

1. Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Jurkovich GJ, et al. Organ injury scaling: spleen and liver (1994 revision). J Trauma 1995;38 : 323–4.

2. DeCou JM, Abrams RS, Gauderer MW. Seat-belt transection of the pararenal vena cava in a 5-year-old child: survival with caval ligation. J Pediatr Surg 1999;34 : 1074–6.

3. Stewart MT, Stone HH. Injuries of the inferior vena cava. Am Surg 1986;52 : 9–13.

4. Burch JM, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL, et al. Injuries of the inferior vena cava. Am J Surg 1988;156 : 548–52.

5. Wiencek RG, Jr., Wilson RF. Inferior vena cava injuries-the challenge continues. Am Surg. 1988;54 : 423–8.

6. Klein SR, Baumgartner FJ, Bongard FS. Contemporary management strategy for major inferior vena caval injuries. J Trauma 1994;37 : 35–41;discussion–2.

7. Ombrellaro MP, Freeman MB, Stevens SL, et al. Predictors of survival after inferior vena cava injuries. Am Surg 1997;63 : 178–83.

8. Porter JM, Ivatury RR, Islam SZ, et al. Inferior vena cava injuries: noninvasive follow-up of venorrhaphy. J Trauma 1997;42 : 913–7; discussion 7–8.

9. van Rooyen PL, Karusseit VO, Mokoena T. Inferior vena cava injuries: a case series and review of the South African experience. Injury 2015;46 : 71–5.

10. Gao JM, Du DY, Zhao XJ, et al. Liver trauma: experience in 348 cases. World J Surg 2003;27 : 703–8.

11. Hirshberg A, Mattox KL. Top knife: the art & craft of trauma surgery. Castle Hill Barns, Shrewsbury, UK: tfm Pub.; 2005.

12. Pringle JH. V. Notes on the arrest of hepatic hemorrhage due to trauma. Ann Surg 1908;48 : 541–9.

13. Pachter HL, Spencer FC, Hofstetter SR, et al. Significant trends in the treatment of hepatic trauma. Experience with 411 injuries. Ann Surg 1992;215 : 492–500;discussion–2.

14. Huerta S, Bui TD, Nguyen TH, et al. Predictors of mortality and management of patients with traumatic inferior vena cava injuries. Am Surg 2006;72 : 290–6.

15. Navsaria PH, de Bruyn P, Nicol AJ. Penetrating abdominal vena cava injuries. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2005;30 : 499–503.

16. Jaunoo SS, Harji DP. Damage control surgery. Int J Surg 2009;7 : 110–3.

17. Stone HH, Strom PR, Mullins RJ. Management of the major coagulopathy with onset during laparotomy. Ann Surg 1983;197 : 532–5.

18. Zacharias SR, Offner P, Moore EE, et al. Damage control surgery. AACN Clin Issues 1999;10 : 95–103; quiz 41–2.

19. Latifi R, Khalaf H. Selective vascular isolation of the liver as part of initial damage control for grade 5 liver injuries: Shouldn’t we use it more frequently? Int J Surg Case Rep 2015;6c:292–5.

20. Biffl WL, Moore EE, Franciose RJ. Venovenous bypass and hepatic vascular isolation as adjuncts in the repair of destructive wounds to the retrohepatic inferior vena cava. J Trauma 1998;45 : 400–3.

21. Croce MA, Fabian TC, Menke PG, et al. Nonoperative management of blunt hepatic trauma is the treatment of choice for hemodynamically stable patients. Results of a prospective trial. Ann Surg 1995;221 : 744–53;discussion 53–5.

22. Veteskova L, Kysela P, Bohata S, et al. [Liver rupture with hemoperitoneum as rare complication of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in young patient with acute myocardial infarction] Czech, Vnitr Lek 2014;60 : 527–30.

23. Vyhnánek F, Duchác V. [Non-surgical approach in blunt injuries to the liver and spleen] Czech, Rozhl Chir 2004;83 : 509–13.

Štítky

Chirurgie všeobecná Ortopedie Urgentní medicína

Článek Editorial

Článek vyšel v časopiseRozhledy v chirurgii

Nejčtenější tento týden

2017 Číslo 4- Metamizol jako analgetikum první volby: kdy, pro koho, jak a proč?

- Nejlepší kůže je zdravá kůže: 3 úrovně ochrany v moderní péči o stomii

- Hojení análních fisur urychlí čípky a gel

- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Vzpomínka na profesora Miloše Hájka

- Editorial

- Ureterointestinal anastomosis in urinary diversion – current opinion

- Liver hemangiomas – when is invasive treatment indicated?

- Treatment of pelvic avulsion fractures in children and adolescents

- K životnímu jubileu docenta Leopolda Plevy

- Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas

- Two-stage surgical treatment of inferior vena cava traumatic rupture including urgent transport to a specialized unit

- Odešel profesor Miroslav Slavík

- Liver resection for recurrent sarcoma with allogenic aortic patch as partial inferior vena cava replacement – case report and review of literature

- Polymastia in unusual localization during pregnancy

- Rozhledy v chirurgii

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Liver hemangiomas – when is invasive treatment indicated?

- Treatment of pelvic avulsion fractures in children and adolescents

- Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas

- Polymastia in unusual localization during pregnancy

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání