-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Prevention of Influenza Virus-Induced Immunopathology by TGF-β Produced during Allergic Asthma

Influenza and asthma represent the two major lung diseases in humans. While most studies have focused on exacerbation of asthma symptoms by influenza virus infection, the effects of asthma on susceptibility to influenza virus infections has been far less studied. Using a novel mouse model of asthma and influenza infection, we show that asthmatic mice are highly resistant to primary challenge with the 2009 influenza pandemic strain (CA04) compared to non-asthmatic mice. The increased resistance of asthmatic mice is not due to the enhanced T or B cell immunity but rather, to a strong anti-inflammatory TGF-beta response triggered by asthma. This study is the first to provide a mechanistic explanation for asthma-mediated protection during the 2009 influenza pandemic.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 11(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005180

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1005180Summary

Influenza and asthma represent the two major lung diseases in humans. While most studies have focused on exacerbation of asthma symptoms by influenza virus infection, the effects of asthma on susceptibility to influenza virus infections has been far less studied. Using a novel mouse model of asthma and influenza infection, we show that asthmatic mice are highly resistant to primary challenge with the 2009 influenza pandemic strain (CA04) compared to non-asthmatic mice. The increased resistance of asthmatic mice is not due to the enhanced T or B cell immunity but rather, to a strong anti-inflammatory TGF-beta response triggered by asthma. This study is the first to provide a mechanistic explanation for asthma-mediated protection during the 2009 influenza pandemic.

Introduction

Influenza A virus is a respiratory pathogen that continues to circulate in humans, causing significant mortality and morbidity. Although antiviral drugs are available, the pandemic threat posed by influenza A viruses is expected to continue due to the lack of an effective long-term influenza vaccine. Despite a major influenza pandemic almost 100 years ago, we still lack a complete understanding of the genetic or physiological risk factors associated with influenza infections.

Asthma has been considered for many years to be a major risk factor for severe influenza infections. For this reason the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends that individuals who have chronic pulmonary disorders, including asthma, be prioritized for vaccination in the event of limited vaccine supply [1]. Asthma is a chronic lung disease characterized by progressively deteriorating lung function. Allergen exposure can induce asthma attacks that are characterized by repetitive cough and wheezing due to airway hyper-responsiveness and airway narrowing. Many allergens can exacerbate asthmatic symptoms including viruses such as human rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus and influenza viruses, which together account for approximately 75% of asthma attacks [2–5]. Thus, the ability of respiratory viruses to provoke asthmatic symptoms is a well-known phenomenon. Furthermore there is a strong association between respiratory viral infections in childhood and later onset of asthma development [6–9].

Survival following influenza virus infection is determined by host resistance, i.e., viral clearance by anti-viral immunity, and tolerance to the damage caused by the virus and host immunity [10]. More specifically, uncontrolled innate immune responses triggered by the virus can result in a fatal outcome from influenza virus infection in both humans [11,12] and animal models [13]. Indeed, virulent strains of influenza A viruses, such as avian H5N1 and Spanish 1918 H1N1, are known for their ability to elicit an excessive inflammatory response or a so-called “cytokine storm” [14]. Because host immune responses can play a pathogenic role during influenza infection, immune suppressive drugs, such as corticosteroids, have been traditionally used to treat severe cases of influenza infection. However, the efficacy of systemic corticosteroids remains controversial [15,16].

Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) is a known immunoregulatory cytokine. The importance of TGF-β in controlling inflammation has been demonstrated in TGF-β deficient mice, which exhibit spontaneous systemic inflammation resulting in postnatal lethality [17,18]. Respiratory viral infections can trigger secretion of TGF-β which plays an important role in attenuating pulmonary inflammation and thereby prolonging survival of the host [19,20]. Specifically, TGF-β promotes differentiation of Tregs which in turn produce additional TGF-β [21] and suppress effector functions of both innate and adaptive immune cells during influenza infections [22,23]. In addition, TGF-β is involved in tissue repair and re-modeling of the respiratory tract through stimulation of matrix protein production, epithelial proliferation and differentiation [24,25]. However, overproduction of TGF-β can be detrimental and has been implicated in development of fibrosis and thickening of airway walls in asthmatics [26].

Given that the prevalence of asthma has increased at an alarming rate, affecting 235 million people in 2011, the impact of asthma on host mucosal immunity warrants detailed investigation. In the present study, we utilized a mouse co-morbidity model of primary influenza infection and allergic airway inflammation to investigate the impact of asthma on host susceptibility to the 2009 pandemic H1N1 A/California/4/2009 (CA04) virus. To our surprise, we found that asthma transiently enhanced survival against primary influenza infection. This increased survival was mediated by high expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, TGF-β1. We further found that TGF-β1 mediated increased survival by preventing tissue injury during influenza infection and not by increasing viral clearance.

Results

OVA sensitized and challenged mice exhibit a typical asthmatic phenotype

To assess the impact of ovalbumin (OVA)-induced allergic airway inflammation on susceptibility to primary influenza A virus infection, we developed a comorbidity mouse model of asthma and influenza (Fig 1A). Asthma was induced by first sensitizing BALB/c mice intraperitoneally (i.p.) with OVA in aluminum hydroxide and then challenging intranasally (i.n.) with soluble OVA. PBS-treated mice were used as a negative control and will be referred to as non-asthmatic mice onwards. Histological analysis showed that the lungs of asthmatic mice were severely inflamed with extensive inflammatory cell infiltration on days 1 and 7 (S1A Fig). Also, inoculation of aerosolized methacholine increased airway resistance (RN), tissue resistance (G), and tissue elastance (H) in asthmatic, but not in non-asthmatic mice (S1B–S1D Fig). In addition, Th2 pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, were highly expressed on day 1 after the last OVA treatment of asthmatic mice but declined to levels similar to those seen in non-asthmatic mice by day 7 (S2 Fig). These results show that the OVA sensitization and challenge protocol induced a typical asthmatic phenotype. We also employed a mouse model of house dust mite (HDM)-induced asthma (S3A Fig). Similar to OVA, HDM treatment elicited a strong cellular infiltration, serum IgE responses, and airway hyperresponsiveness (S3B–S3D Fig). These two models allowed us to investigate the susceptibility of asthmatic mice to influenza virus infection. Asthmatic mice were routinely infected on day 7 after the last allergen treatment, unless otherwise indicated.

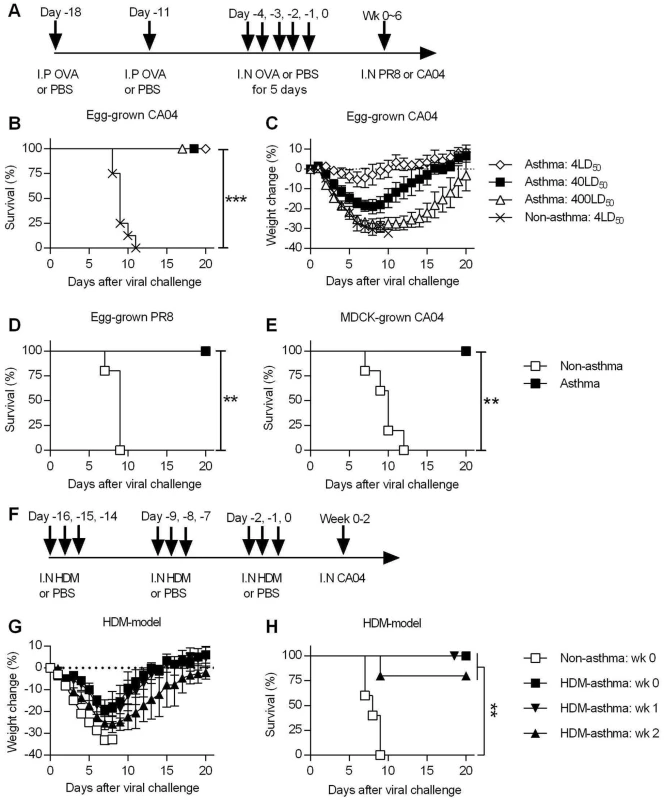

Fig. 1. Asthmatic mice are highly resistant to influenza A virus challenge.

(A) The general experimental procedure used in this study. Mice were first sensitized to OVA by two i.p. injections, followed by i.n. OVA treatment for 5 consecutive days to induce asthma. Control non-asthmatic mice received PBS only. Asthmatic and non-asthmatic mice were challenged i.n. with PR8 or CA04 influenza A virus at different time points after the last OVA treatment. (B and C) At day 7 after the last PBS or OVA treatment, asthmatic and non-asthmatic mice were infected with either 4, 40 or 400LD50 of CA04 influenza virus (8 mice/group). Infected mice were monitored for survival (B) and weight loss (C). (D and E) Groups of non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice were challenged with either egg-grown PR8 strain (2x103 PFU) (D) or MDCK grown CA04 virus (6x104 TCID50) (E). Infected mice were monitored for 20 days for survival (5 mice/group). (F) A mouse model of HDM-induced asthma. (G and H) HDM-induced asthmatic and non-asthmatic mice were i.n. challenged with CA04 virus either 1, 2, or 3 weeks following HDM challenge. Weight loss (G) and survival (H) were monitored for 20 days (5 mice/group). *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. Asthmatic mice are highly resistant to influenza A virus infection

To assess the susceptibility of asthmatic mice to influenza A virus infection, non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice were challenged with different doses of egg-grown CA04 2009 pandemic strain virus. While all non-asthmatic succumbed to a 4LD50 viral challenge dose, all asthmatic mice infected with doses of up to 400LD50 surprisingly survived challenge (Fig 1B). While a dose of 4LD50 caused little morbidity, i.e., minimal weight loss, in asthmatic mice, higher doses did cause noticeable morbidity around day 7 p.i., yet full recovery was observed by day 20 p.i (Fig 1C). Thus, asthmatic mice withstood high doses of the 2009 pandemic strain, demonstrating their remarkable resistance to influenza infection. This resistance was not specific to the CA04 strain, as asthmatic mice also survived lethal infection with the H1N1 A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (PR8) virus (Fig 1D). In addition, we infected mice with MDCK cell-grown virus to determine whether the resistance of asthmatic mice was specific to egg-grown viruses. Consistent with the above results, asthmatic mice exhibited a high level of resistance to lethal challenge with MDCK-grown CA04 virus (Fig 1E). This shows that asthmatic mice are resistant to influenza infection and that this resistance is not dependent on conditions of viral propagation. Consistent with the OVA model, HDM-asthmatic mice also exhibited minimal morbidity (Fig 1G and S3E Fig) and enhanced resistance to CA04 infection (Fig 1H).

Endotoxin is a common contaminant of OVA [27] and HDM [28] preparations; LPS i.n. inoculation has been shown to be protective against influenza infections [29]. However, control, non-sensitized mice treated with i.n. OVA were not protected, demonstrating that the increased resistance was not caused by endotoxin contamination in the OVA preparation (S4 Fig). Furthermore, i.n treatment with Escherichia coli 0111:B4.9 LPS using an equivalent amount of endotoxin detected in our OVA stock did not confer resistance in mice (S3 Fig) Thus, the observed protection in OVA-asthmatic mice is not due to the endotoxin contamination.

Asthma does not impact mucosal anti-viral humoral immunity

To determine whether the increased resistance of asthmatic mice was due to increased adaptive immunity, we investigated the influence of asthma on virus-specific antibody responses. CA04-specific total antibody, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b levels in BALF were comparable between non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice on day 7 p.i. (Fig 2A–2D). In addition, hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titers in non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice were similar on days 5 and 7 post-CA04 infection (Fig 2E). Analysis of CD19+ B cell expression showed that numbers of B cells in the lungs were also essentially comparable between the two groups (Fig 2F). Therefore, no changes in virus-specific humoral immune responses were observed that could account for the increased resistance observed following asthma.

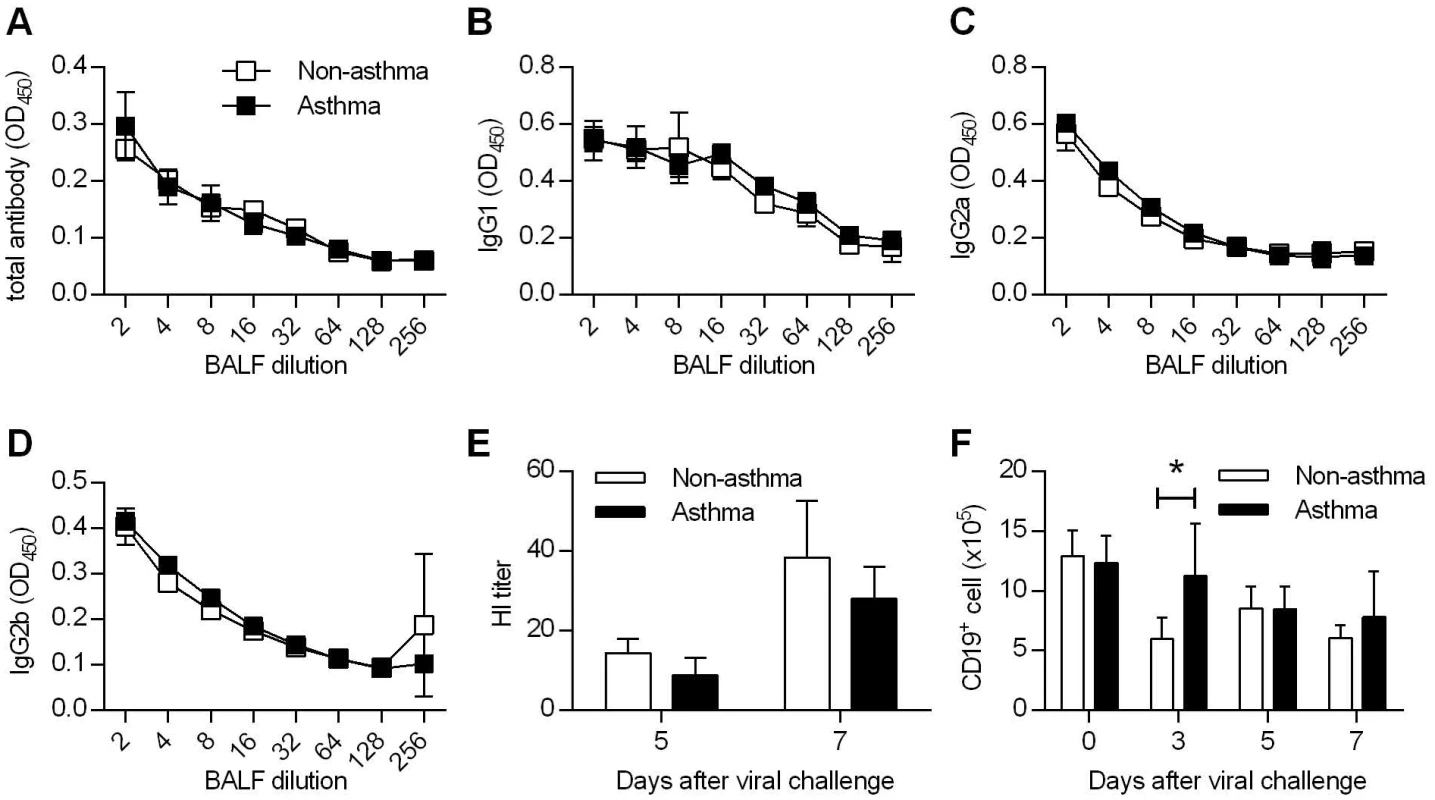

Fig. 2. Comparable humoral immunity in non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice.

(A to D) Non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice were infected with 4LD50 of CA04 virus. Seven days after primary challenge, BALF were tested for total (A), IgG1 (B), IgG2a (C), and IgG2b (D) antibody binding (4–5 mice/group). (E) Hemagglutination inhibition titers of BALF samples were determined (4–5 mice/group). (F) The numbers of CD19+ B cells were enumerated in the lung at various time points after CA04 virus infection (4 mice/group). *P<0.05. T cells are dispensable for enhanced protection to influenza virus infection in asthmatic mice

To examine the impact of asthma on mucosal T cell responses, lungs were harvested for flow cytometry at different time points to enumerate T cell recruitment. Absolute numbers of CD4+ T cells were higher in asthmatic mice relative to non-asthmatic mice on day 3 post-infection but were identical on days 5 and 7 (Fig 3A). Percentages of CD4+ T cells were also similar in non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice at all-time points tested (Fig 3B). Influenza A virus nucleoprotein (NP)-specific CD8+ T cell numbers were slightly higher in non-asthmatic mice on day 5 p.i. (Fig 3C). Similarly, the percentages of NP+CD8+ T cells were increased in non-asthmatic mice on days 3 and 5 but were equivalent on day 7 p.i. (Fig 3D). We further examined the amounts of the T cell effector molecule, granzyme (gzm) B in BALF. On day 7 p.i., which is the peak of the NP+CD8+ T cell response, levels of gzm B did not differ between asthmatic mice and non-asthmatic mice (Fig 3E). Overall, these results indicate that increased resistance in asthmatic mice was not attributed to altered T cell immunity.

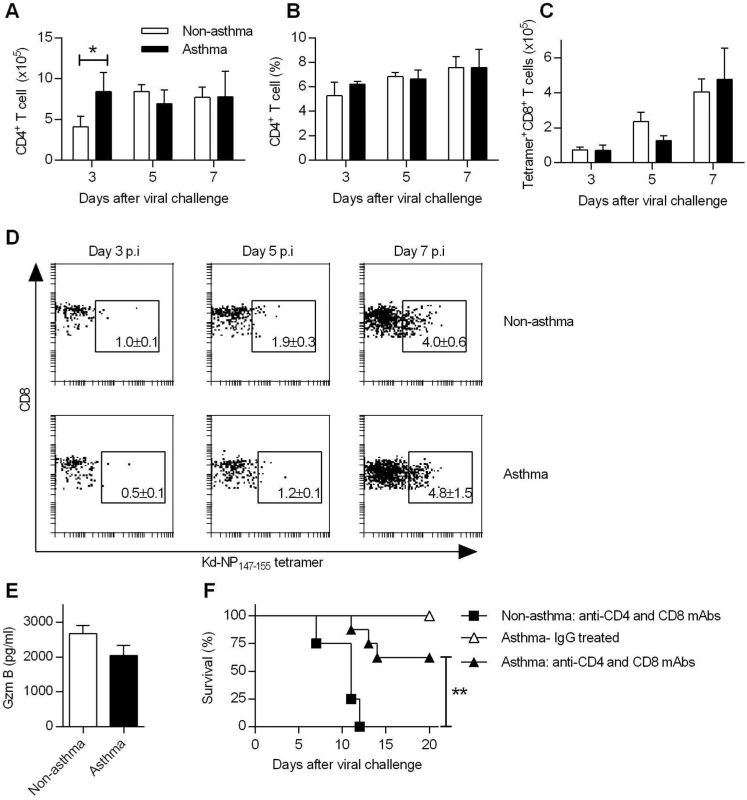

Fig. 3. Increased resistance in asthmatic mice is T cell independent.

(A to D) Groups of non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice were infected with CA04 virus on day 7 after the last OVA or PBS inoculation. Lungs were isolated on days 3, 5, and 7 post-infection and single cell suspensions were stained for CD4 (A and B), and nucleoprotein (NP)-specific CD8 (C) cells (4 mice/group). A representative dot plot for each group is shown with percentages of NP+CD8+ T cells in the lung (D). (E) BALF Gzm B levels on day 7 post-infection were quantified by ELISA (4–5 mice/group). (F) T cells were depleted by i.p. injection of GK1.5 and 53–6.72 mAb after the last PBS or OVA inoculation. Control mice were treated with rat IgG. Control and T cell-depleted mice were challenged with CA04 virus and monitored for survival (4–8 mice/group). *P<0.05, **P<0.01. In addition to virus-specific CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells responses, FoxP3+ CD4+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) and T helper 17 cells (Th17) are also induced during influenza infection. We observed differences in numbers of Tregs between non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice (S5A Fig). However, depletion of CD4+ or CD4+ and CD8+ T cells did not abrogate the resistance of asthmatic mice (Fig 3F and S5B and S5C Fig). In contrast, non-asthmatic mice depleted of CD4+ or CD4+ and CD8+ T cells had 100% mortality. Furthermore, mucosal L-17 responses were comparable between non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice (S5D Fig) and IL-17 receptor deficiency had no significant impact on survival of asthmatic mice (S5E Fig). Thus, CD4+/CD8+ T cells, Tregs or Th17 cells were not required for the enhanced resistance of asthmatic mice to CA04 infection.

Innate immune responses are not required for the increased resistance of asthmatic mice to CA04 infection

Since the resistance of asthmatic mice could not be attributed to the antigen-specific adaptive immunity, we next investigated the importance of innate immune responses. Because greater amounts of IFN-α, a potent antiviral cytokine, were found in asthmatic mice during the early stages of infection (S6A Fig), we used mice deficient in IFN-I receptor expression (IFN-α/βR-/-) to investigate the role of IFN-I in asthma-mediated resistance to influenza. Asthmatic IFN-α/βR-/- mice survived a lethal challenge of CA04 virus while non-asthmatic mice succumbed to infection (Fig 4A). Consistent with the survival data, asthmatic IFN-α/βR-/- mice had lower weight loss compared to non-asthmatic mice following CA04 infection (Fig 4B). Thus, absence of IFN-I signaling did not compromise the resistance of asthmatic mice.

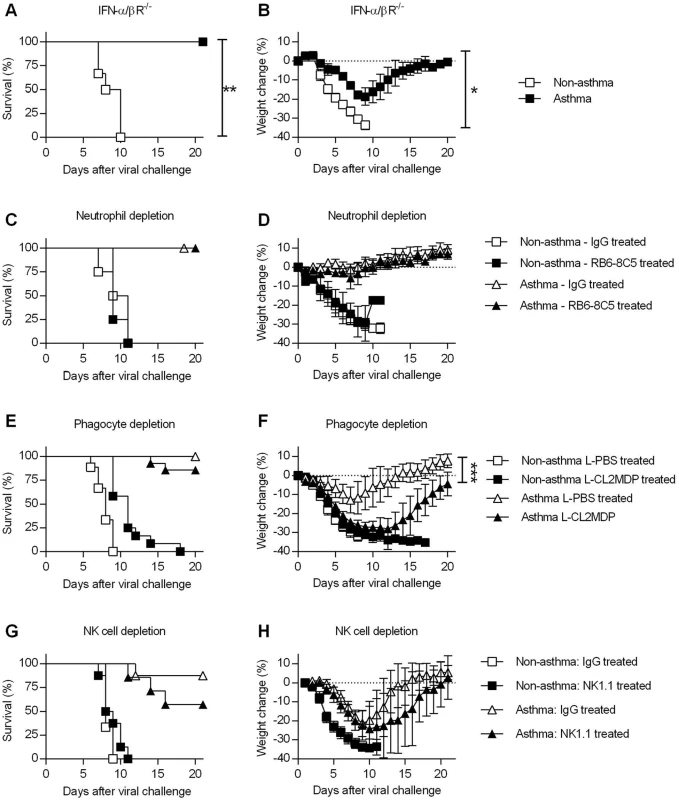

Fig. 4. Innate immune responses are dispensable for the increased resistance of asthmatic mice.

(A and B) OVA-induced allergic inflammation was induced in IFN-α/βR-/- mice as described in the legend for Fig 1. Non-asthmatic and asthmatic IFN-α/βR-/- mice were challenged with CA04 virus and were monitored for survival (A) and weight loss (B) (5–6 mice/group). (C to H) Non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice were depleted of various innate immune cells, infected, and monitored for survival. Mice were treated with RB6-8C5 rat mAb for neutrophil depletion (C and D) (4–6 mice/group), clodronate liposomes (L-CL2MDP) for phagocyte depletion (E and F) (9–14 mice/group), and NK1.1 rat mAb for NK cell depletion (G and H) (6–8 mice/group). Control mice were treated with rat IgG or PBS liposomes (L-PBS). Survival and weight loss were monitored for 20 days. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. We also performed a series of in vivo depletion experiments to investigate the contribution of various innate immune cells to asthma-induced resistance. Following i.n. challenge with OVA or PBS, asthmatic and non-asthmatic mice were treated with RB6-8C5 mAb, liposomal clodronate, or NK1.1 mAb to deplete neutrophils, macrophages, or NK cells, respectively. Control mice received normal rat IgG or liposomal PBS. After neutrophil depletion, there was no effect in asthmatic or non-asthmatic mice (Fig 4C and 4D). Phagocytic cell depletion did not significantly reduce the survival rate of asthmatic mice compared to liposomal PBS-treated asthmatic mice (Fig 4E) but did increase morbidity (Fig 4F). NK cell depletion had no significant effect on either survival or weight loss of non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice (Fig 4G and 4H). Thus, although altered recruitment of innate immune cells was observed in asthmatic mice (S6B–S6D Fig), individual innate immune cell types did not contribute significantly to the increased resistance of asthmatic mice.

Enhanced survival is correlated with reduced immunopathology but not viral burden in asthmatic mice

The results presented above indicated that the increased resistance of asthmatic mice was not due to enhanced anti-viral immunity and suggested that virus-induced immunopathology might be downregulated in asthmatic mice, which could account for the observed increased survival rates. Although pro-inflammatory cytokines are integral components of an effective immune response against infection, excessive production can cause tissue damage and is associated with mortality [30]. Thus, we next tested whether the extent of the cytokine storm was decreased in asthmatic mice. Following a lethal infection with CA04 virus, protein levels of various bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) cytokines were quantified by cytometric bead array. We found that asthmatic mice had lower levels of IL-6, IL-10, MCP-1, IFN-γ, and TNF compared to non-asthmatic mice (Fig 5A–5E). Similar trends were observed using PR8 virus, with asthmatic mice producing significantly decreased amounts of cytokines (S7 Fig). The type 2 innate lymphoid cell-associated cytokines, amphiregulin, IL-5, and IL-13, were also downregulated in asthmatic mice (S8 Fig). Thus, enhanced survival of asthmatic mice correlates with reduced cytokine responses.

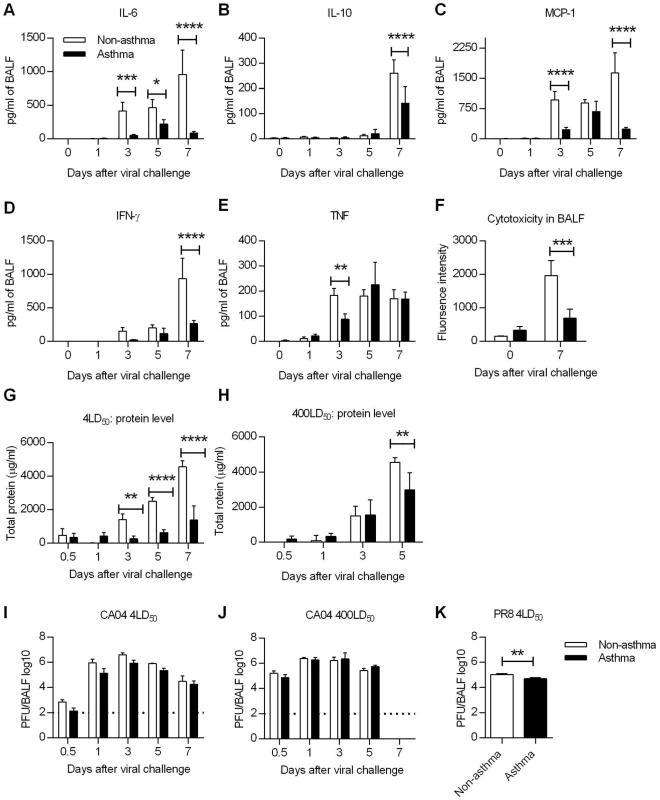

Fig. 5. Influenza virus induced immunopathology is reduced in asthmatic mice.

Non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice were infected i.n. with 4LD50 of the CA04 virus on day 7 after the last PBS or OVA treatment. The lungs were harvested and homogenized for cytokine quantification at various times following influenza infection. (A to E) Pulmonary cytokine levels were measured by cytometric bead array. (F) Cytotoxicity in BALF was determined by measuring glucose 6-phosphate. (G and H) Total protein levels in BALF were measured using the Pierce BCA Protein Kit following challenge with 4 LD50 (G) or 400LD50 (H) of CA04. (I to K) Viral burdens were determined in BALF after challenge with either 4 LD50 (I) or 400LD50 (J) of CA04 or 4LD50 of PR8 (K). Each bar indicates mean ± SD of 3–5 mice/group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. Since cytokine analysis showed decreased inflammatory responses in asthmatic mice, we next determined if tissue damage was also attenuated. To address this, BALF samples collected from uninfected and day 7-infected mice were tested for cytotoxicity and total protein levels. Cytotoxicity testing, which measures the extent of dying and damaged cells, revealed that cytotoxicity was significantly reduced in asthmatic mice on day 7 p.i. compared to that in non-asthmatic mice although baseline cytotoxicity was higher in asthmatic mice compared to non-asthmatic mice (Fig 5F). Total protein, another marker of lung injury and edema, was greater in asthmatic mice only at day 1 p.i.; levels were thereafter significantly less compared to those in non-asthmatic mice (Fig 5G). Even with a challenge dose of 400LD50, asthmatic mice had reduced amounts of protein in the BALF on day 5 p.i. compared to non-asthmatic mice (Fig 5H). Interestingly, influenza virus infection triggered reduced tissue damping and elastance in asthmatic mice, suggesting that the pulmonary function is less compromised in asthmatic mice (S9 Fig). Taken together, these results demonstrate that lung injury was significantly reduced in asthmatic mice as evaluated by cytokine production, cytotoxicity and protein levels in BALF.

To determine whether the reduced immunopathology of asthmatic was due to increased viral clearance, asthmatic and non-asthmatic mice were infected i.n. with either 4LD50 or 400LD50 of CA04 and BALF samples were collected for virus PFU enumeration. Viral replication was observed in both non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice. Although with a challenge dose of 4LD50, viral titers were approximately a half-log less in asthmatic mice on days 0.5, 1, 3 and 5 p.i., the differences were not statistically significant (Fig 5I and 5J). Similarly, after PR8 infection, day 7 viral titers were only slightly different between non-asthmatic and asthmatic (Fig 5K). These data show that the reduced susceptibility of asthmatic mice correlated with reduced immunopathology but not with viral burden. Consistent with the viral burden data, lung epithelial cell expression of sialic acid (SA) receptors (α-2,3 SA and α-2,6 SA), which meditate influenza viral entry, were unaltered in asthmatic mice (S10A and S10B Fig).

Conditional deletion of TGF-β receptor II renders asthmatic mice susceptible to CA04

One key cytokine that plays pro - and anti-inflammatory roles during asthma pathogenesis is TGF-β1 [26]. TGF-β1 initiates and regulates inflammatory responses as well as airway remodeling [31]. Given the potent immunoregulatory properties of TGF-β1, we determined whether TGF-β1 in asthmatic mice could account for reduced immunopathology following influenza infection. To examine this, TGF-β1 levels in BALF following i.n. OVA treatment were measured by ELISA. The peak of TGF-β1 expression in asthmatic mice was during weeks 0 and 1 post-OVA challenge (Fig 6A), and significantly declined by week 2. TGF-β1 levels continued to decrease during weeks 3, 4 and 5 but were still higher than the baseline levels detected in non-asthmatic mice. By week 6, the amounts of TGF-β1 in asthmatic mice had declined to background levels. We next quantified TGF-β1 protein levels following CA04 challenge. Consistent with the above findings, asthmatic mice had significantly higher levels of TGF-β1 on days 0, 1, 3, and 5 p.i. compared to non-asthmatic mice (Fig 6B). By day 7 p.i., TGF-β1 levels were comparable between non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice.

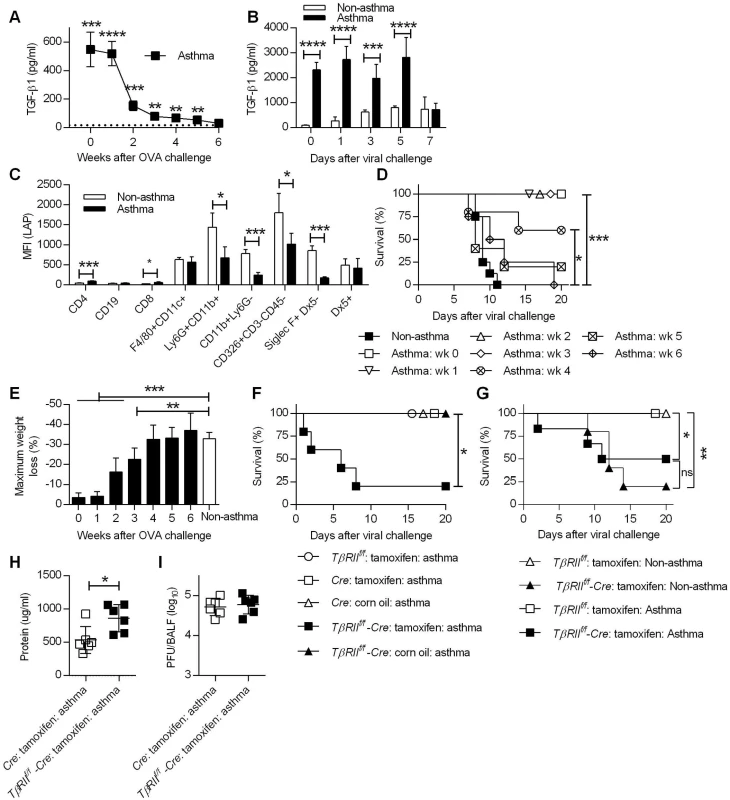

Fig. 6. TGF-β mediates increased resistance in asthmatic mice.

(A) TGF-β1 levels in BALF of noninfluenza-infected asthmatic mice (4 mice/group) were determined by ELISA. The dotted line represents background TGF-β1 levels in BALF of non-asthmatic mice. (B) TGF-β1 levels in BALF after CA04 infection were determined by Luminex (3–4 mice/group). (C) Cell surface expression of LAP was measured on day 7 after the last OVA inoculation (4 mice/group). (D and E) Asthmatic mice (5–8 mice/group) infected at different time points after the last OVA treatment were monitored for survival (D) and weight loss (E). (F and G) Survival of TβRIIf/f-Cre and control mice were monitored for survival after infection of either 2x103 PFU (F) or 50 PFU (G) of CA04 (4–8 mice/group). (H and I) Total protein levels (H) and viral burdens (I) in BALF were measured on day 3 post-infection (6 mice/group). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. Because increased levels of TGF-β1 were detected in asthmatic mice, we next sought to identify the cells responsible for TGF-β1 production. It is widely accepted that TGF-β1 is constitutively produced in a biologically inactive pro-TGF-β1 form, which exists in complex with latency-associated protein (LAP) as a latent-TGF-β1 [32]. Therefore, staining of cells with anti-LAP mAb, which recognizes LAP, pro-TGF-β and latent-TGF-β, can be used to identify the cellular source of TGF-β. To examine this, we harvested lungs of non-asthmatic and asthmatic mice on day 7 post-OVA challenge for flow cytometry analysis and median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of LAP was quantitated for various cell types. The majority of LAP-expressing cells were innate immune cells (e.g., F4/80+CD11c+, Ly6G+CD11b+, CD11b+ Ly6G-, Siglec-F+DX5- cells) and epithelial cells (CD326+CD3-CD45- cells) (Fig 6C). LAP expression by these cell types was lower in asthmatic mice compared to non-asthmatic mice, suggesting ongoing secretion of TGF-β1, which correlates with lower cell surface expression as observed by others in a mouse model of asthma [33]. This is also in agreement with clinical data showing that cells recovered from asthmatic patients secrete greater amounts of TGF-β1 than cells from non-asthmatic patients [34,35]. The above findings led us to hypothesize that TGF-β1 suppresses immune-mediated tissue injury and thereby prevents influenza-induced mortality. To test this hypothesis, we first investigated if TGF-β1 production correlated with the window of resistance to influenza infection following asthma induction. At various time points after OVA treatment, asthmatic mice were i.n. infected with a lethal dose of CA04 virus, and survival and weight loss were monitored for 20 days. Survival analysis showed that the increased resistance of asthmatic mice to influenza declined over time (Fig 6D). Asthmatic mice that were infected on week 0, 1, 2, or 3 post-OVA treatment had a 100% survival rate. The survival rate decreased when asthmatic mice were challenged with influenza on week 4, however the survival rate of these mice was still significantly higher when compared to non-asthmatic mice. Finally, when influenza infection was performed on week 5 or 6 post-OVA treatment, survival rates of asthmatic and non-asthmatic mice were comparable. Consistent with the survival data, weight loss patterns increased when asthmatic mice were infected at later time points post-OVA challenge (Fig 6E). Overall, the reduced susceptibility of asthmatic mice was not permanent but declined over time and closely correlated with BALF TGF-β1 levels.

To directly determine the protective role of TGF-β1 against influenza infection, we utilized conditional TGF-β receptor II (TGF-βRII) deficient mice. Constitutive deficiency in TGF-β1 or TGF-βRII is embryonically lethal due to uncontrolled spontaneous inflammation [36,37]. To circumvent this issue, we created conditional knockout mice by crossing TβRIIf/f mice with Ubc-CreERT2 mice to generate tamoxifen-inducible TGF-βRII deficient mice (TβRIIf/f-Cre). PCR analysis demonstrated tamoxifen-induced deletion of the floxed TβRII allele and quantitative evaluation by flow cytometry confirmed a significant reduction in TβRII expression (S11 Fig). Using this conditional knockout mouse, we showed that deletion of TGF-βRII in asthmatic mice resulted in decreased survival after CA04 virus infection while all of the wildtype asthmatic mice had 100% survival (Fig 6F). The protective role of TGF-β during influenza infection [19] complicates assessment of TGF-β as a mediator of increased resistance in asthmatic mice. To overcome this problem, we normalized infection to the CA04 virus LD50 for TβRIIf/f deficient mice (Fig 6G). Infection of non-asthmatic TβRIIf/f deficient mice with 50 PFU of CA04 virus resulted in 20% survival and asthma provided only marginally increased protection in these animals. Furthermore, asthmatic TβRIIf/f deficient mice had increased total protein levels in BALF on day 3 post-viral challenge (Fig 6H), despite having viral burdens that were similar to wild-type asthmatic mice (Fig 6I). We conclude that deletion of TβRII abolished the resistance of asthmatic mice to influenza virus infection and that TGF-β mediated resistance is likely to be due to suppression of influenza virus-triggered immunopathology.

Discussion

In the present study, asthmatic mice were found to be highly resistant to influenza A virus infection, including the 2009 influenza pandemic strain. It is particularly surprising that asthmatic mice were able to resist H1N1 CA04 virus infection at doses as high as 400LD50 which corresponds to 2 x 105 viral PFU. This extraordinary resistance did not depend on the viral strain as asthmatic mice were also resistant to influenza PR8 virus. However, enhanced resistance was transient and lasted no longer than 4 weeks following acute asthma. Interestingly, no correlation was seen between increased survival and viral burden. This strongly suggests that the increased survival of asthmatic mice was not due to enhanced antiviral immunity but rather to increased tolerance to influenza infection-mediated tissue damage.

Influenza can kill the host either by direct pathology that is mediated by viral replication or by inducing a damaging inflammatory response. The absence of a correlation between viral burden and survival rate seen in asthmatic mice suggests that the induced protection was due to suppression of virus-induced immunopathology. This hypothesis was supported by reduced lung injury in asthmatic mice as determined by pulmonary cytokine expression, airway protein levels (indicative of severe edema), and cell death as measured by a cytotoxicity assay. These assays clearly indicated that asthmatic mice suffered less severe virus-mediated immunopathology. Consistent with our animal data, ex vivo study using primary human bronchial cells have shown that epithelial cells from asthmatic donors are also resistant to influenza virus-mediated pathology [38].

The two main cytokines associated with an anti-inflammatory state are IL-10 and TGF-β. In our co-morbidity mouse model of asthma and influenza, IL-10 was absent prior to CA04 infection, however, it was produced at later time points, i.e., day 7 p.i. Thus, it is reasonable to believe that IL-10 was expressed in response to tissue injury, with the lower levels observed in asthmatic mice correlating with reduced lung tissue pathology compared to non-asthmatic mice. In contrast, high levels of TGF-β1 were detected in asthmatic mice prior to infection. This is consistent with numerous human [39–42] and mouse studies [43], showing that TGF-β1 is transiently produced in large amounts during and after asthma exacerbations. Thus, we speculated that increased expression of TGF-β1 could mediate the increased survival of asthmatic mice through suppression of harmful immune responses. Indeed, the kinetics of TGF-β1 expression in BALF correlated strongly with longevity of resistance in asthmatic mice and its continuing increased production during influenza virus infection. Most importantly, a strong link between TGF-β1 and reduced susceptibility of asthmatic mice to influenza virus infection was demonstrated using conditional TGF-βRII knockout mice in which deletion of the TβRII allele completely abrogated the resistance of asthmatic mice. Consistent with our observations, others have reported that in vivo neutralization of TGF-β increases susceptibility to infection to both H5N1 virus and the 2009 pandemic virus [19]. In particular, Carlson et al. speculated that the protective role of TGF-β may involve modulation of immunopathology since TGF-β neutralization had a minimal effect on viral burden [19].

The mechanism responsible for TGF-β-mediated protection in asthmatic mice may involve prevention of tissue injury as opposed to augmented tissue repair. Newly identified cell types termed innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) participate in restoring airway epithelial integrity and lung tissue homeostasis during influenza virus infection through production of amphiregulin [44], which was in fact, reduced in asthmatic mice. Thus, it is likely that severe tissue injury did not occur in asthmatic mice that would have otherwise necessitated an ILC/amphiregulin response for tissue repair. This idea is further supported by the fact that neither BALF cytotoxicity nor total protein levels in asthmatic mice increased significantly above their respective pre-infection levels. However, an important question remains as to how TGF-β1 suppresses influenza virus-induced tissue damage. The most likely mechanism is that TGF-β1 preserves the overall integrity of the lung by directly inhibiting cytokine production from various immune cells. Indeed, asthmatic mice exhibited less severe asthma exacerbation following influenza infection. A homeostatic function for TGF-β in the lung has been previously described by Morris et al. [45]. In their work, the authors showed that active TGF-β in the lung can influence the pulmonary immune milieu by maintaining the anti-inflammatory state of alveolar macrophages through upregulation of expression of the inhibitory receptor, CD200 [46]. Consistent with the above reports, we also showed that in the absence of TGF-β receptor II, total protein levels increased, which indicated enhanced tissue injury, but without enhanced viral replication, and this correlated with loss of protection in asthmatic mice.

This study is the first to report an enhanced resistance of asthmatic mice to influenza that is dependent on TGF-β1. Ishikawa et al. have identified NK cells as the major mediator of increased resistance in asthmatic mice [47]. Their conclusions were based upon the use of anti-asialoGM1 serum to deplete NK cells and abrogate resistance. However, asialoGM1 is expressed on a wide variety of cells [48–53]. Indeed, a recent study showed that anti-asialoGM1 serum depletes, in addition to NK cells, basophils and, thereby abolishes IgE-mediated chronic cutaneous allergic inflammation [53]. Therefore, the reduced resistance in anti-asialoGM1 treated mice in the study by Ishikawa et al. might have been due to the simultaneous depletion of a number of different cell types and/or the lack of an asthmatic phenotype in the absence of basophils. In contrast, a specific depletion of NK cell using NK1.1 mAb did not reverse the resistance of asthmatic C57Bl/6 mice to influenza. This conclusively shows that the resistance to influenza observed in our model was not dependent on NK cells. Furthermore it is important to note that the asthma model used by Ishikawa et al. did not induce typical asthma phenotype. Thus, the apparent inconsistency between our observations and their results was not surprising.

The data presented in this study appear to contradict epidemiological findings suggesting that asthma is associated with increased rates of hospital admission during influenza, severe disease and death [54–59]. More recent reports, however, have suggested that among hospitalized patients during influenza pandemics, asthmatics are actually less likely to die compared to non-asthmatics [59,60]. Increased survival among hospitalized asthmatic patients during the 2009 pandemic may be due to the fact that these individuals are aware of their condition and seek medical care sooner than their non-asthmatic counterparts, and therefore, receive antiviral and/or corticosteroid treatment in a more timely fashion [61]. In our mouse model, asthmatic mice were not treated with corticosteroid or antiviral drugs and yet exhibited better survival following influenza infection. The apparent discrepancy between the human and mouse data may arise from differences in the timing of viral and allergic challenge. The sequence of events is critically important because an active form of TGF-β, a mediator of protection, is not constitutively expressed at high levels in asthmatic patients [62] or in mice. High expression of TGF-β above its baseline is inducible by an allergic antigen challenge but its expression is transient in nature as shown in this study. Given that only approximately 2% of all asthmatic patients have uncontrolled persistent allergic asthma [63] and that 85% of asthma exacerbations are triggered by viral infections [64], it can be speculated that most asthmatic patients do not have upregulated TGF-β expression at the time of viral challenge and therefore are not protected against viral infections. However, in our experiments, asthmatic mice were infected when TGF-β expression was highly upregulated by allergic challenge. Thus, primary infection of influenza-naïve adult mice after allergen induced airway inflammation may not necessarily accurately mimic the clinical setting and this may explain the discrepancy between human observational data and results from the present mouse study. It will be of considerable interest to directly determine whether non-viral induced asthma exacerbations in humans are followed by a transient period of increased resistance to influenza infection. To the best of our knowledge, such clinical data are not available.

We have recently reported that asthmatic mice are more susceptible to secondary heterologous challenge with CA04 virus [65]. In that study, we utilized a secondary influenza challenge model in which asthmatic mice were reinfected with influenza virus at week 6 post OVA challenge when TGF-β expression is at the baseline. We found that CA04-specific antibody responses were suppressed during secondary challenge and as a result, asthmatic mice were more susceptible to influenza infection. We now know that asthmatic mice express large amounts of active TGF-β for up to 5 weeks in the airway. Thus, it is likely that the lack of TGF-β responses at the time of secondary challenge failed to protect asthmatic mice and this further support the conclusion of the present study that asthma associated TGF-β response is protective but the protection is only transient. Based on our previous work and the present studies, we propose that future co-morbidity study of allergic airway inflammation and influenza should investigate the impact of asthma on the host susceptibility to viral infections when TGF-β is at the baseline, i.e when lung homeostasis has been restored after allergic challenge, to better mimic infections of asthmatic patients.

In conclusion, we report for the first time that increased expression of TGF-β1 in asthmatic mice confers resistance to influenza virus infection through suppression of tissue injury. Our study provides compelling evidence that TGF-β1 would have therapeutic potential in preventing influenza-related mortality. A therapeutic measure that is not dependent on antigen specificity is particularly important in the event of an influenza pandemic when antigen-matched vaccines are not immediately available. It will be of great interest to ascertain whether asthmatic mice are also protected against H5N1, a highly pathogenic strain known to cause an exacerbated cytokine storm.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

Animal care and experimental protocols were in accordance with the NIH “Guide for the Care and Use of the laboratory Animals” and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Albany Medical College (Protocol Number 11–04004).

Co-morbidity mouse model of asthma and influenza

Eight-week-old C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories through a contract with the National Cancer Institute. BALB/c IFN-IR-/- mice were kindly provided by Dr. Daniel Portnoy (University of California, Berkeley, CA) and mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in the Animal Research Facility at Albany Medical College. To induce acute allergic lung inflammation, the mice were first sensitized against OVA (Sigma-Aldrich) by injecting 10 μg of OVA in aluminum hydroxide (General Chemical) i.p. twice at weekly intervals. One week after the last immunization, the sensitized mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane and challenged i.n. with 100 μg of OVA in PBS for 5 consecutive days. Control, non-asthmatic mice were sensitized and challenged with PBS. At various time points after the final i.n. OVA inoculation, asthmatic and non-asthmatic mice were challenged i.n. with either CA04 or PR8. For HDM-asthma model, mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane and i.n. exposed to 50 μg of house dust mite (HDM) extract (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus: Greer Laboratories) in PBS for three consecutive days every three weeks. Control non-asthmatic mice received PBS or LPS from E. coli 0111:B4 (0.64 endotoxin unit in 50uL PBS). At the indicated time points after the last HDM inoculation, asthmatic and non-asthmatic mice were infected i.n. with a 4LD50 of CA04. The influenza type A viruses were propagated in 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs (Charles River) or in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells.

Plaque assay

At indicated time points after i.n. challenge, bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BALF) were harvested by lavaging the lungs with 1 ml of PBS. BALF were aliquoted and stored at -80°C for plaque assays. Serial dilutions of BALF were added to MDCK cells monolayers for viral plaque enumeration.

Cytokine and granzyme B analysis

For cytokine analysis, BALF samples were centrifuged at 300 x g for 10 min at 4°C and the cell-free BALF samples were aliquoted and stored at -80°C. Protein levels of TGF-β1 in BALF were analyzed by either ELISA (eBioscience) or mouse Bio-Plex Luminex assays (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturers’ instructions. Levels of IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, MCP-1, IFN-γ, and TNF in lung homogenates were measured by cytometric bead array (BD Biosciences). Granzyme B (gzmB) levels in BALF were determined by a mouse gzmB ELISA kit (eBioscience).

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxic levels were quantitated by Vybrant Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Molecular Probes). In brief, this assay measures the cytosolic enzyme glucose 6-phosphagte dehydrogenase (G6PD) that is released from damaged cells into the BALF. G6PD generates NADPH, which in turn, leads to reduction of resazurin into red-fluorescent resorufin. The fluorescence signal was measured by a plate reader and the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) correlated with the number of dead cells.

Total protein assay

The total protein levels in the cell free fraction of BALF were determined using a Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific Pierce).

Flow cytometry

The lungs were harvested and incubated with 0.25 mg/ml of DNAse I (Roche Diagnositics), 2 mg/ml of collagenase D (Roche Diagnostics), and 1 mM of MgCl2 for 45 min at 37°C. The digested lungs were passed through a 40 μm nylon cell strainer, followed by 5 min incubation with ammonium-chloride-potassium lysis buffer to obtain red blood cell-depleted single-cell suspensions. Live cells were enumerated based on trypan blue staining. 5 x 105 cells were incubated with Fixable Viability Dye (FVD) (eFluor 780; eBioscience) for 30 min on ice, followed by incubation with 2.4G2 mAb (anti-mouse FcγIII/II receptor) for 15 min. Fc receptor-blocked cells were then stained with mixtures of anti-mouse surface antigen mAbs: anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5) (FITC; BD Pharmingen), anti-CD19 (clone 1D3) (PE; BD Pharmingen), anti-CD8 (clone 53–6.7) (PE-Cy7; BD Pharmingen), anti-F4/80 (clone BM8) (PE; eBioscience), anti-CD11c (clone N418) (APC-Cy7; BioLegend), anti-Ly6G (clone 1A8) (PE-Cy7; Biolegend), anti-CD11b (clone M1/70) (FITC; eBioscience), anti-CD326/EpCAM (clone 48.8) (PE; eBioscience), anti-CD3 (clone 145-2C11) (FITC; BD Pharmingen), anti-CD45 (clone 30-F11) (PE-Cy7; BioLegend), anti-Siglec F (clone E50-2440) (PE; BD Pharmingen), anti-CD49b (clone Dx5) (FITC; eBioscience), and anti-LAP (clone TW7-16B4) (APC; BioLegend). Stained cells were analyzed using a FACSCanto flow cytometer. The cell debris was gated out based on forward and side scatter and live cells were gated in based on FVD staining. Median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of APC–conjugated anti-mouse LAP was measured for the indicated subsets of cells. To analyze influenza A virus nucleoprotein (NP)-specific CD8+ T cells, cells were further stained with APC-conjugated H-2Kd NP tetramer (TYQRTRALV) for 45 min at 4°C. The tetramer was obtained through the NIH Tetramer Facility.

TβRII conditional knockout mice

Floxed TβRII (TβRIIf/f) and Ubc-CreERT2 (Cre) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. TβRIIf/f mice were crossed with tamoxifen inducible Cre transgenic mice to generate homozygous TβRII conditional knockout (TβRIIf/f-Cre) mice, heterozygous TβRII knockout mice (TβRIIf/+-Cre) and control mice (TβRIIf/f, TβRIIf/+, TβRII+/+-Cre). For the induction of Cre, 2 mg of tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich) in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected i.p. once/day for 5 consecutive days. OVA-sensitized mice were treated with tamoxifen prior to i.n. OVA treatment. Cre recombinase-mediated deletion of the floxed TβRII gene was confirmed by PCR for TβRIInull and flow cytometry analysis for TGF-βRII expression (S8 Fig).

Influenza A virus-specific antibodies

Cell-free BALF samples collected on day 7 post-CA04 virus infection were analyzed for antigen-specific antibodies by ELISA. A 96-well MaxiSorp plate (Nunc) was coated with 2 μg/ml of H1N1 A/California/09/2009 monovalent vaccine (Sanofi Pasteur) and incubated at 4°C overnight. Wells were then washed with PBS + 0.05% Tween (Sigma) and blocked with PBS + 1% FCS for 2 hr at room temp. After washing, the wells were incubated with serial 2-fold sample dilutions for 2 hr at room temp. The plates were then incubated with biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies specific for IgG1, IgG2A, or IgG2b (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 hr and then horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin was added (Biosource). After 30 min incubation, the plates were extensively washed and TMB peroxidase substrate (BD Biosciences) was added. The reaction was stopped by adding 1.8N H2SO4 and optical density was measured at 450 nm using a Power-Wave HT microplate reader (BioTek Instruments). Antibody titer is expressed as the reciprocal dilution that gave 50% of the maximum optical density.

Hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay

Serially-diluted cell free-BALF was mixed with 4 hemagglutination units of CA04 virus in V-bottom 96-well plates. After 30 min incubation, 0.5% of chicken red blood cells (Lampire Biological Laboratories) were added and incubated for additional 1 hr at room temp. The HI titer was defined as the reciprocal of the last dilution that prevented viral hemagglutination activity.

In vivo immune cell depletion prior to CA04 virus challenge

Various immune cells including neutrophils, phagocytic cells, NK cells and T cells were depleted in vivo after the last OVA/PBS inoculation but before CA04 virus infection. For T cell depletion, mice were treated i.p. with 0.5 mg of anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5) (Bio X Cell) and anti-CD8 (clone 53–6.72) (Bio X Cell) mAbs on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, and challenged with CA04 virus on day 7. For neutrophil depletion, mice were injected i.p. with 0.5 mg of anti-Ly-6C/G (RB6-8C5) (Maine Biotechnology) mAb on days 4 and 5. For phagocyte depletion, 50 ul of liposomes containing clodronate (clodronateliposomes.com) were administered i.n. on days 4 and 5. For NK cell depletion, 0.5 mg of NK1.1 (PK-136) (Maine Biotechnology) mAb was injected i.p. on days 4 and 5. Rat IgG and liposomal-PBS were used as controls for the above depletion experiments. The efficiency of cell depletion in the lungs (ranging from 80 to 99%) was confirmed one day prior to infection (day 6) by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test with Welch correction for comparison of two groups and one - or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for comparison of multiple groups. Survival data were analyzed with log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test using GraphPad Prism 6 software (San Diego, CA). A P value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. (2013) Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Recomm Rep 62 : 1–43.

2. Johnston SL, Pattemore PK, Sanderson G, Smith S, Lampe F, et al. (1995) Community study of role of viral infections in exacerbations of asthma in 9–11 year old children. BMJ 310 : 1225–1229. 7767192

3. Heymann PW, Carper HT, Murphy DD, Platts-Mills TA, Patrie J, et al. (2004) Viral infections in relation to age, atopy, and season of admission among children hospitalized for wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol 114 : 239–247. 15316497

4. Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, Blumkin AK, Edwards KM, et al. (2009) The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med 360 : 588–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804877 19196675

5. Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, et al. (1995) Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. The Group Health Medical Associates. N Engl J Med 332 : 133–138. 7800004

6. Sigurs N, Bjarnason R, Sigurbergsson F, Kjellman B (2000) Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy is an important risk factor for asthma and allergy at age 7. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161 : 1501–1507. 10806145

7. O'Callaghan-Gordo C, Bassat Q, Diez-Padrisa N, Morais L, Machevo S, et al. (2013) Lower respiratory tract infections associated with rhinovirus during infancy and increased risk of wheezing during childhood. A cohort study. PLoS One 8: e69370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069370 23935997

8. Schauer U, Hoffjan S, Bittscheidt J, Kochling A, Hemmis S, et al. (2002) RSV bronchiolitis and risk of wheeze and allergic sensitisation in the first year of life. Eur Respir J 20 : 1277–1283. 12449185

9. Lemanske RF Jr., Jackson DJ, Gangnon RE, Evans MD, Li Z, et al. (2005) Rhinovirus illnesses during infancy predict subsequent childhood wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol 116 : 571–577. 16159626

10. Damjanovic D, Small CL, Jeyanathan M, McCormick S, Xing Z (2012) Immunopathology in influenza virus infection: uncoupling the friend from foe. Clin Immunol 144 : 57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.05.005 22673491

11. de Jong MD, Simmons CP, Thanh TT, Hien VM, Smith GJ, et al. (2006) Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. Nat Med 12 : 1203–1207. 16964257

12. Bermejo-Martin JF, Ortiz de Lejarazu R, Pumarola T, Rello J, Almansa R, et al. (2009) Th1 and Th17 hypercytokinemia as early host response signature in severe pandemic influenza. Crit Care 13: R201. doi: 10.1186/cc8208 20003352

13. Kobasa D, Jones SM, Shinya K, Kash JC, Copps J, et al. (2007) Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus. Nature 445 : 319–323. 17230189

14. Taubenberger JK, Morens DM (2008) The pathology of influenza virus infections. Annu Rev Pathol 3 : 499–522. 18039138

15. Martin-Loeches I, Lisboa T, Rhodes A, Moreno RP, Silva E, et al. (2011) Use of early corticosteroid therapy on ICU admission in patients affected by severe pandemic (H1N1)v influenza A infection. Intensive Care Med 37 : 272–283. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2078-z 21107529

16. Diaz E, Martin-Loeches I, Canadell L, Vidaur L, Suarez D, et al. (2012) Corticosteroid therapy in patients with primary viral pneumonia due to pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza. J Infect 64 : 311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.12.010 22240033

17. Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, et al. (1992) Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature 359 : 693–699. 1436033

18. Kulkarni AB, Huh CG, Becker D, Geiser A, Lyght M, et al. (1993) Transforming growth factor beta 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90 : 770–774. 8421714

19. Carlson CM, Turpin EA, Moser LA, O'Brien KB, Cline TD, et al. (2010) Transforming growth factor-beta: activation by neuraminidase and role in highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog 6: e1001136. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001136 20949074

20. Williams AE, Humphreys IR, Cornere M, Edwards L, Rae A, et al. (2005) TGF-beta prevents eosinophilic lung disease but impairs pathogen clearance. Microbes Infect 7 : 365–374. 15784186

21. D'Alessio FR, Tsushima K, Aggarwal NR, West EE, Willett MH, et al. (2009) CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs resolve experimental lung injury in mice and are present in humans with acute lung injury. J Clin Invest 119 : 2898–2913. doi: 10.1172/JCI36498 19770521

22. Antunes I, Kassiotis G (2010) Suppression of innate immune pathology by regulatory T cells during Influenza A virus infection of immunodeficient mice. J Virol 84 : 12564–12575. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01559-10 20943986

23. Betts RJ, Prabhu N, Ho AW, Lew FC, Hutchinson PE, et al. (2012) Influenza A virus infection results in a robust, antigen-responsive, and widely disseminated Foxp3+ regulatory T cell response. J Virol 86 : 2817–2825. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05685-11 22205730

24. Crosby LM, Waters CM (2010) Epithelial repair mechanisms in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 298: L715–731. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00361.2009 20363851

25. Buckley S, Shi W, Barsky L, Warburton D (2008) TGF-beta signaling promotes survival and repair in rat alveolar epithelial type 2 cells during recovery after hyperoxic injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L739–748. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00294.2007 18245268

26. Yang YC, Zhang N, Van Crombruggen K, Hu GH, Hong SL, et al. (2012) Transforming growth factor-beta1 in inflammatory airway disease: a key for understanding inflammation and remodeling. Allergy 67 : 1193–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02880.x 22913656

27. Watanabe J, Miyazaki Y, Zimmerman GA, Albertine KH, McIntyre TM (2003) Endotoxin contamination of ovalbumin suppresses murine immunologic responses and development of airway hyper-reactivity. J Biol Chem 278 : 42361–42368. 12909619

28. Hammad H, Chieppa M, Perros F, Willart MA, Germain RN, et al. (2009) House dust mite allergen induces asthma via Toll-like receptor 4 triggering of airway structural cells. Nat Med 15 : 410–416. doi: 10.1038/nm.1946 19330007

29. Shinya K, Okamura T, Sueta S, Kasai N, Tanaka M, et al. (2011) Toll-like receptor pre-stimulation protects mice against lethal infection with highly pathogenic influenza viruses. Virol J 8 : 97. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-97 21375734

30. Balk RA (2000) Pathogenesis and management of multiple organ dysfunction or failure in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Clin 16 : 337–352, vii. 10768085

31. Li MO, Wan YY, Sanjabi S, Robertson AK, Flavell RA (2006) Transforming growth factor-beta regulation of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol 24 : 99–146. 16551245

32. Dubois CM, Laprise MH, Blanchette F, Gentry LE, Leduc R (1995) Processing of transforming growth factor beta 1 precursor by human furin convertase. J Biol Chem 270 : 10618–10624. 7737999

33. Magnan A, Retornaz F, Tsicopoulos A, Brisse J, Van Pee D, et al. (1997) Altered compartmentalization of transforming growth factor-beta in asthmatic airways. Clin Exp Allergy 27 : 389–395. 9146931

34. Vignola AM, Chanez P, Chiappara G, Merendino A, Zinnanti E, et al. (1996) Release of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) and fibronectin by alveolar macrophages in airway diseases. Clin Exp Immunol 106 : 114–119. 8870708

35. Hastie AT, Kraft WK, Nyce KB, Zangrilli JG, Musani AI, et al. (2002) Asthmatic epithelial cell proliferation and stimulation of collagen production: human asthmatic epithelial cells stimulate collagen type III production by human lung myofibroblasts after segmental allergen challenge. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165 : 266–272. 11790666

36. Oshima M, Oshima H, Taketo MM (1996) TGF-beta receptor type II deficiency results in defects of yolk sac hematopoiesis and vasculogenesis. Dev Biol 179 : 297–302. 8873772

37. Dickson MC, Martin JS, Cousins FM, Kulkarni AB, Karlsson S, et al. (1995) Defective haematopoiesis and vasculogenesis in transforming growth factor-beta 1 knock out mice. Development 121 : 1845–1854. 7600998

38. Samarasinghe AE, Woolard SN, Boyd KL, Hoselton SA, Schuh JM, et al. (2014) The immune profile associated with acute allergic asthma accelerates clearance of influenza virus. Immunol Cell Biol 92 : 449–459. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.113 24469764

39. Tillie-Leblond I, Pugin J, Marquette CH, Lamblin C, Saulnier F, et al. (1999) Balance between proinflammatory cytokines and their inhibitors in bronchial lavage from patients with status asthmaticus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159 : 487–494. 9927362

40. Redington AE, Madden J, Frew AJ, Djukanovic R, Roche WR, et al. (1997) Transforming growth factor-beta 1 in asthma. Measurement in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156 : 642–647. 9279252

41. Batra V, Musani AI, Hastie AT, Khurana S, Carpenter KA, et al. (2004) Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid concentrations of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1, TGF-beta2, interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 after segmental allergen challenge and their effects on alpha-smooth muscle actin and collagen III synthesis by primary human lung fibroblasts. Clin Exp Allergy 34 : 437–444. 15005738

42. Nomura A, Uchida Y, Sakamoto T, Ishii Y, Masuyama K, et al. (2002) Increases in collagen type I synthesis in asthma: the role of eosinophils and transforming growth factor-beta. Clin Exp Allergy 32 : 860–865. 12047432

43. Kumar RK, Herbert C, Foster PS (2004) Expression of growth factors by airway epithelial cells in a model of chronic asthma: regulation and relationship to subepithelial fibrosis. Clin Exp Allergy 34 : 567–575. 15080809

44. Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Abt MC, Alenghat T, Ziegler CG, et al. (2011) Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat Immunol 12 : 1045–1054. doi: 10.1031/ni.2131 21946417

45. Morris DG, Huang X, Kaminski N, Wang Y, Shapiro SD, et al. (2003) Loss of integrin alpha(v)beta6-mediated TGF-beta activation causes Mmp12-dependent emphysema. Nature 422 : 169–173. 12634787

46. Snelgrove RJ, Goulding J, Didierlaurent AM, Lyonga D, Vekaria S, et al. (2008) A critical function for CD200 in lung immune homeostasis and the severity of influenza infection. Nat Immunol 9 : 1074–1083. doi: 10.1038/ni.1637 18660812

47. Ishikawa H, Sasaki H, Fukui T, Fujita K, Kutsukake E, et al. (2012) Mice with asthma are more resistant to influenza virus infection and NK cells activated by the induction of asthma have potentially protective effects. J Clin Immunol 32 : 256–267. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9619-2 22134539

48. Slifka MK, Pagarigan RR, Whitton JL (2000) NK markers are expressed on a high percentage of virus-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. J Immunol 164 : 2009–2015. 10657652

49. Lee U, Santa K, Habu S, Nishimura T (1996) Murine asialo GM1+CD8+ T cells as novel interleukin-12-responsive killer T cell precursors. Jpn J Cancer Res 87 : 429–432. 8641977

50. Trambley J, Bingaman AW, Lin A, Elwood ET, Waitze SY, et al. (1999) Asialo GM1(+) CD8(+) T cells play a critical role in costimulation blockade-resistant allograft rejection. J Clin Invest 104 : 1715–1722. 10606625

51. Wiltrout RH, Santoni A, Peterson ES, Knott DC, Overton WR, et al. (1985) Reactivity of anti-asialo GM1 serum with tumoricidal and non-tumoricidal mouse macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 37 : 597–614. 3884721

52. Kataoka S, Konishi Y, Nishio Y, Fujikawa-Adachi K, Tominaga A (2004) Antitumor activity of eosinophils activated by IL-5 and eotaxin against hepatocellular carcinoma. DNA Cell Biol 23 : 549–560. 15383175

53. Nishikado H, Mukai K, Kawano Y, Minegishi Y, Karasuyama H (2011) NK cell-depleting anti-asialo GM1 antibody exhibits a lethal off-target effect on basophils in vivo. J Immunol 186 : 5766–5771. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100370 21490162

54. Morris SK, Parkin P, Science M, Subbarao P, Yau Y, et al. (2012) A retrospective cross-sectional study of risk factors and clinical spectrum of children admitted to hospital with pandemic H1N1 influenza as compared to influenza A. BMJ Open 2: e000310. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000310 22411932

55. Plessa E, Diakakis P, Gardelis J, Thirios A, Koletsi P, et al. (2010) Clinical features, risk factors, and complications among pediatric patients with pandemic influenza A (H1N1). Clin Pediatr (Phila) 49 : 777–781.

56. Jain S, Kamimoto L, Bramley AM, Schmitz AM, Benoit SR, et al. (2009) Hospitalized patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza in the United States, April-June 2009. N Engl J Med 361 : 1935–1944. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906695 19815859

57. Libster R, Bugna J, Coviello S, Hijano DR, Dunaiewsky M, et al. (2010) Pediatric hospitalizations associated with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in Argentina. N Engl J Med 362 : 45–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907673 20032320

58. Kloepfer KM, Olenec JP, Lee WM, Liu G, Vrtis RF, et al. (2012) Increased H1N1 infection rate in children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185 : 1275–1279. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201109-1635OC 22366048

59. Van Kerkhove MD, Vandemaele KA, Shinde V, Jaramillo-Gutierrez G, Koukounari A, et al. (2011) Risk factors for severe outcomes following 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection: a global pooled analysis. PLoS Med 8: e1001053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001053 21750667

60. Louie JK, Acosta M, Samuel MC, Schechter R, Vugia DJ, et al. (2011) A novel risk factor for a novel virus: obesity and 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1). Clin Infect Dis 52 : 301–312. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq152 21208911

61. Myles P, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Semple MG, Brett SJ, Bannister B, et al. (2013) Differences between asthmatics and nonasthmatics hospitalised with influenza A infection. Eur Respir J 41 : 824–831. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00015512 22903963

62. Halwani R, Al-Muhsen S, Al-Jahdali H, Hamid Q (2011) Role of transforming growth factor-beta in airway remodeling in asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 44 : 127–133. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0027TR 20525803

63. Peters SP, Ferguson G, Deniz Y, Reisner C (2006) Uncontrolled asthma: a review of the prevalence, disease burden and options for treatment. Respir Med 100 : 1139–1151. 16713224

64. Busse WW, Lemanske RF Jr., Gern JE (2010) Role of viral respiratory infections in asthma and asthma exacerbations. Lancet 376 : 826–834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61380-3 20816549

65. Furuya Y, Roberts S, Hurteau GJ, Sanfilippo AM, Racine R, et al. (2014) Asthma increases susceptibility to heterologous but not homologous secondary influenza. J Virol 88 : 9166–9181. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00265-14 24899197

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Here I Am, Despite Myself

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 9- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Familiární středomořská horečka

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Ross River Virus: Many Vectors and Unusual Hosts Make for an Unpredictable Pathogen

- Distinct but Spatially Overlapping Intestinal Niches for Vancomycin-Resistant and Carbapenem-Resistant

- Intracellular Survival of Depends on Uptake and Degradation of Extracellular Matrix Glycosaminoglycans by Macrophages

- Type IX Secretion Substrates Are Cleaved and Modified by a Sortase-Like Mechanism

- Structural and Functional Characterization of Anti-A33 Antibodies Reveal a Potent Cross-Species Orthopoxviruses Neutralizer

- Suppression of a Natural Killer Cell Response by Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Peptides

- Inhibition of Translation Initiation by Protein 169: A Vaccinia Virus Strategy to Suppress Innate and Adaptive Immunity and Alter Virus Virulence

- Enteropathogenic Uses NleA to Inhibit NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation

- Flavodoxin-Like Proteins Protect from Oxidative Stress and Promote Virulence

- Cullin4 Is Pro-Viral during West Nile Virus Infection of Mosquitoes

- The NLRP3 Inflammasome and IL-1β Accelerate Immunologically Mediated Pathology in Experimental Viral Fulminant Hepatitis

- DYRK2 Negatively Regulates Type I Interferon Induction by Promoting TBK1 Degradation via Ser527 Phosphorylation

- A KSHV microRNA Directly Targets G Protein-Coupled Receptor Kinase 2 to Promote the Migration and Invasion of Endothelial Cells by Inducing CXCR2 and Activating AKT Signaling

- The Operon Essential for Biofilm and Rugose Colony Development in

- ADAP2 Is an Interferon Stimulated Gene That Restricts RNA Virus Entry

- The Role of the Antiviral APOBEC3 Gene Family in Protecting Chimpanzees against Lentiviruses from Monkeys

- The Deacetylase Sirtuin 1 Regulates Human Papillomavirus Replication by Modulating Histone Acetylation and Recruitment of DNA Damage Factors NBS1 and Rad51 to Viral Genomes

- Experimental Malaria in Pregnancy Induces Neurocognitive Injury in Uninfected Offspring via a C5a-C5a Receptor Dependent Pathway

- Intrahepatic Transcriptional Signature Associated with Response to Interferon-α Treatment in the Woodchuck Model of Chronic Hepatitis B

- Adipose Tissue Is a Neglected Viral Reservoir and an Inflammatory Site during Chronic HIV and SIV Infection

- Infection Is Associated with Impaired Hepatic Dimethylarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase Activity and Disruption of Nitric Oxide Synthase Inhibitor/Substrate Homeostasis

- Conserved Motifs within Hepatitis C Virus Envelope (E2) RNA and Protein Independently Inhibit T Cell Activation

- The RelA/SpoT Homolog and Stringent Response Regulate Survival in the Tick Vector and Global Gene Expression during Starvation

- Hybridization in Parasites: Consequences for Adaptive Evolution, Pathogenesis, and Public Health in a Changing World

- KSHV Latency Locus Cooperates with Myc to Drive Lymphoma in Mice

- Immunostimulatory Defective Viral Genomes from Respiratory Syncytial Virus Promote a Strong Innate Antiviral Response during Infection in Mice and Humans

- Retraction: Extreme Resistance as a Host Counter-counter Defense against Viral Suppression of RNA Silencing

- Appetite for a Foodborne Infection

- Here I Am, Despite Myself

- Microbial Regulation of p53 Tumor Suppressor

- Fiat Luc: Bioluminescence Imaging Reveals In Vivo Viral Replication Dynamics

- Knocking on Closed Doors: Host Interferons Dynamically Regulate Blood-Brain Barrier Function during Viral Infections of the Central Nervous System

- Rapid Lymphatic Dissemination of Encapsulated Group A Streptococci Lymphatic Vessel Endothelial Receptor-1 Interaction

- Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Infection of Chimpanzees () Shares Features of Both Pathogenic and Non-pathogenic Lentiviral Infections

- Epicellular Apicomplexans: Parasites “On the Way In”

- The Depsipeptide Romidepsin Reverses HIV-1 Latency

- Skin-Derived C-Terminal Filaggrin-2 Fragments Are -Directed Antimicrobials Targeting Bacterial Replication

- Type IV Pili Composed of Sequence Invariable Pilins Are Masked by Multisite Glycosylation

- Heterosexual Transmission of Subtype C HIV-1 Selects Consensus-Like Variants without Increased Replicative Capacity or Interferon-α Resistance

- Prevention of Influenza Virus-Induced Immunopathology by TGF-β Produced during Allergic Asthma

- Global Analysis of Mouse Polyomavirus Infection Reveals Dynamic Regulation of Viral and Host Gene Expression and Promiscuous Viral RNA Editing

- Modulation of the Host Lipid Landscape to Promote RNA Virus Replication: The Picornavirus Encephalomyocarditis Virus Converges on the Pathway Used by Hepatitis C Virus

- Intrinsic MyD88-Akt1-mTOR Signaling Coordinates Disparate Tc17 and Tc1 Responses during Vaccine Immunity against Fungal Pneumonia

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Epicellular Apicomplexans: Parasites “On the Way In”

- Fiat Luc: Bioluminescence Imaging Reveals In Vivo Viral Replication Dynamics

- Knocking on Closed Doors: Host Interferons Dynamically Regulate Blood-Brain Barrier Function during Viral Infections of the Central Nervous System

- A KSHV microRNA Directly Targets G Protein-Coupled Receptor Kinase 2 to Promote the Migration and Invasion of Endothelial Cells by Inducing CXCR2 and Activating AKT Signaling

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání