-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Bleeding ‘downhill’ esophageal varices associated with benign superior vena cava obstruction: case report and literature review

Background:

Proximal or ‘downhill’ esophageal varices are a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Unlike the much more common distal esophageal varices, which are most commonly a result of portal hypertension, downhill esophageal varices result from vascular obstruction of the superior vena cava (SVC). While SVC obstruction is most commonly secondary to malignant causes, our review of the literature suggests that benign causes of SVC obstruction are the most common cause actual bleeding from downhill varices. Given the alternative pathophysiology of downhill varices, they require a unique approach to management. Variceal band ligation may be used to temporize acute variceal bleeding, and should be applied on the proximal end of the varix. Relief of the underlying SVC obstruction is the cornerstone of definitive treatment of downhill varices.Case presentation:

A young woman with a benign superior vena cava stenosis due to a tunneled internal jugular vein dialysis catheter presented with hematemesis and melena. Urgent upper endoscopy revealed multiple ‘downhill’ esophageal varices with stigmata of recent hemorrhage. As there was no active bleeding, no endoscopic intervention was performed. CT angiography demonstrated stenosis of the SVC surrounding the distal tip of her indwelling hemodialysis catheter. The patient underwent balloon angioplasty of the stenotic SVC segment with resolution of her bleeding and clinical stabilization.Conclusion:

Downhill esophageal varices are a distinct entity from the more common distal esophageal varices. Endoscopic therapies have a role in temporizing active variceal bleeding, but relief of the underlying SVC obstruction is the cornerstone of treatment and should be pursued as rapidly as possible. It is unknown why benign, as opposed to malignant, causes of SVC obstruction result in bleeding from downhill varices at such a high rate, despite being a less common etiology of SVC obstruction.Keywords:

Case report, Esophagus, Bleeding varices, Vascular obstruction, Superior vena cava, Proximal esophageal varices

Authors: Michael Loudin 1*; Sharon Anderson 2; Barry Schlansky 1

Authors place of work: Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road, Portland, OR L-461, USA. 1; Department of Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Oregon Health & Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road, Portland, OR, USA. 2

Published in the journal: BMC Gastroenterology 2016, 16:134

Category: Case report

doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-016-0548-7© 2016 The Author(s).

Open access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found online at: http://bmcgastroenterol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12876-016-0548-7Summary

Background:

Proximal or ‘downhill’ esophageal varices are a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Unlike the much more common distal esophageal varices, which are most commonly a result of portal hypertension, downhill esophageal varices result from vascular obstruction of the superior vena cava (SVC). While SVC obstruction is most commonly secondary to malignant causes, our review of the literature suggests that benign causes of SVC obstruction are the most common cause actual bleeding from downhill varices. Given the alternative pathophysiology of downhill varices, they require a unique approach to management. Variceal band ligation may be used to temporize acute variceal bleeding, and should be applied on the proximal end of the varix. Relief of the underlying SVC obstruction is the cornerstone of definitive treatment of downhill varices.Case presentation:

A young woman with a benign superior vena cava stenosis due to a tunneled internal jugular vein dialysis catheter presented with hematemesis and melena. Urgent upper endoscopy revealed multiple ‘downhill’ esophageal varices with stigmata of recent hemorrhage. As there was no active bleeding, no endoscopic intervention was performed. CT angiography demonstrated stenosis of the SVC surrounding the distal tip of her indwelling hemodialysis catheter. The patient underwent balloon angioplasty of the stenotic SVC segment with resolution of her bleeding and clinical stabilization.Conclusion:

Downhill esophageal varices are a distinct entity from the more common distal esophageal varices. Endoscopic therapies have a role in temporizing active variceal bleeding, but relief of the underlying SVC obstruction is the cornerstone of treatment and should be pursued as rapidly as possible. It is unknown why benign, as opposed to malignant, causes of SVC obstruction result in bleeding from downhill varices at such a high rate, despite being a less common etiology of SVC obstruction.Keywords:

Case report, Esophagus, Bleeding varices, Vascular obstruction, Superior vena cava, Proximal esophageal varicesBackground

‘Downhill’ esophageal varices are an uncommon etiology of gastrointestinal bleeding, estimated to account for approximately 0.1 % of all cases of variceal hemorrhage [1, 2]. The most common reported cause of SVC compression is from mediastinal malignancy such as thymoma, lymphoma or lung cancer, accounting for approximately 60 % of cases [3]. Although bleeding ‘downhill’ varices are rare, non-bleeding varices have been reported to occur in 30 % of patients with benign or malignant SVC obstruction undergoing screening upper endoscopy [1]. SVC obstruction diverts venous return from the head and upper torso through collaterals such as the azygous or innominate veins to bypass the obstruction. The proximal and mid esophageal veins drain into the azygous and innominate veins, and the increased pressure and collateralization result in the development of esophageal varices supplied from the superior aspect of the esophagus and extending distally [4].

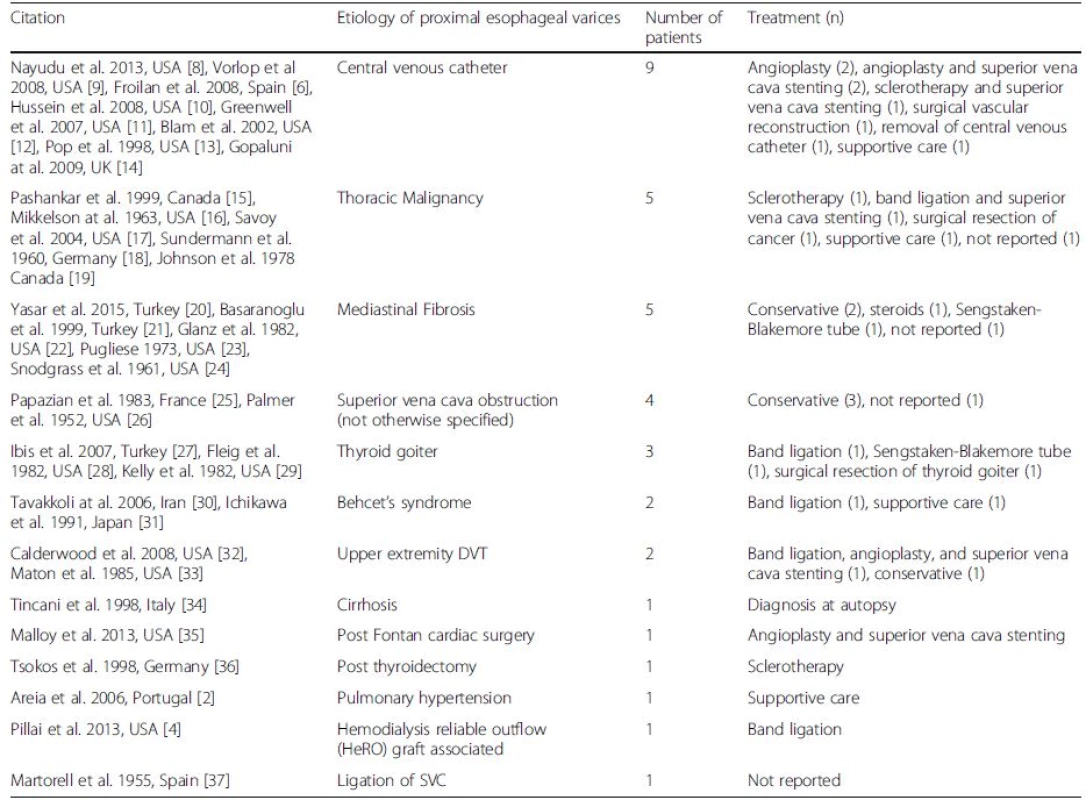

We performed a literature search within the MEDLINE and SCOPUS databases using the search strings “proximal varices” and “downhill varices” to identify case reports or studies involving “downhill” varices. Interestingly, while malignancy is described as the most common underlying etiology of SVC obstruction (60 %), based on a review of the available literature, malignancy is the reported etiology for only 14 % of SVC obstruction resulting in downhill variceal bleeding (Table 1). The most common etiology of bleeding downhill varices is a complication related to a venous catheter (27 %), with our patient representing the 10th reported case in the literature. Other benign etiologies of SVC obstruction such as mediastinal fibrosis, behcet’s, goiter, thrombus or post-surgical complications account for the majority of the remaining reported cases of benign obstruction resulting in bleeding. Some theories have been proposed regarding why downhill varices bleed less than distal esophageal varices. These include less exposure to gastric acid, the fact that proximal esophageal varices are submucosal as opposed to the more superficially located distal esophageal varices which are found in the subepithelial venous plexus, and that patients with proximal esophageal varices generally lack the coagulopathy associated with liver dysfunction commonly found in patients with distal esophageal varices [5]. However no explanation is available as to why benign etiologies of SVC obstruction leading to bleeding downhill varices are reported in the literature at a much higher frequency than those associated with malignant obstruction, despite malignancy being the predominant cause of SVC obstruction in the general population.

Tab. 1. Etiologies and therapies of proximal esophageal variceal hemorrhage in case series

USA United States of America, SVC superior vena cava, DVT deep vein thrombosis The treatment of bleeding ‘downhill’ esophageal varices involves a multidisciplinary team including thoracic or vascular surgery, interventional radiology, and the endoscopist. When possible, correction of the underlying cause of SVC obstruction is the cornerstone of management, and may involve the angiographic dilation of the narrowed SVC segment, surgical reconstruction or resection of the involved SVC, or cancer therapies such as chemotherapy or external beam radiation [6, 7]. Endoscopic therapy with variceal band ligation or sclerotherapy (at the proximal end of the varix from which blood flow is supplied) or balloon tamponade can be attempted when bleeding is severe to temporize bleeding prior to definitive therapy. Endoscopic approaches are technically limited by the proximity of the varices to the larynx and may be painful due to the somatic innervation of the proximal esophagus.

In this paper we report the 10th case of bleeding downhill varices secondary to complications from a central venous catheter, confirming this as the most commonly reported underlying etiology of bleeding downhill varices. It remains uncertain why benign, as opposed to malignant, causes of SVC obstruction result in bleeding from downhill varices at such a high rate.

Case presentation

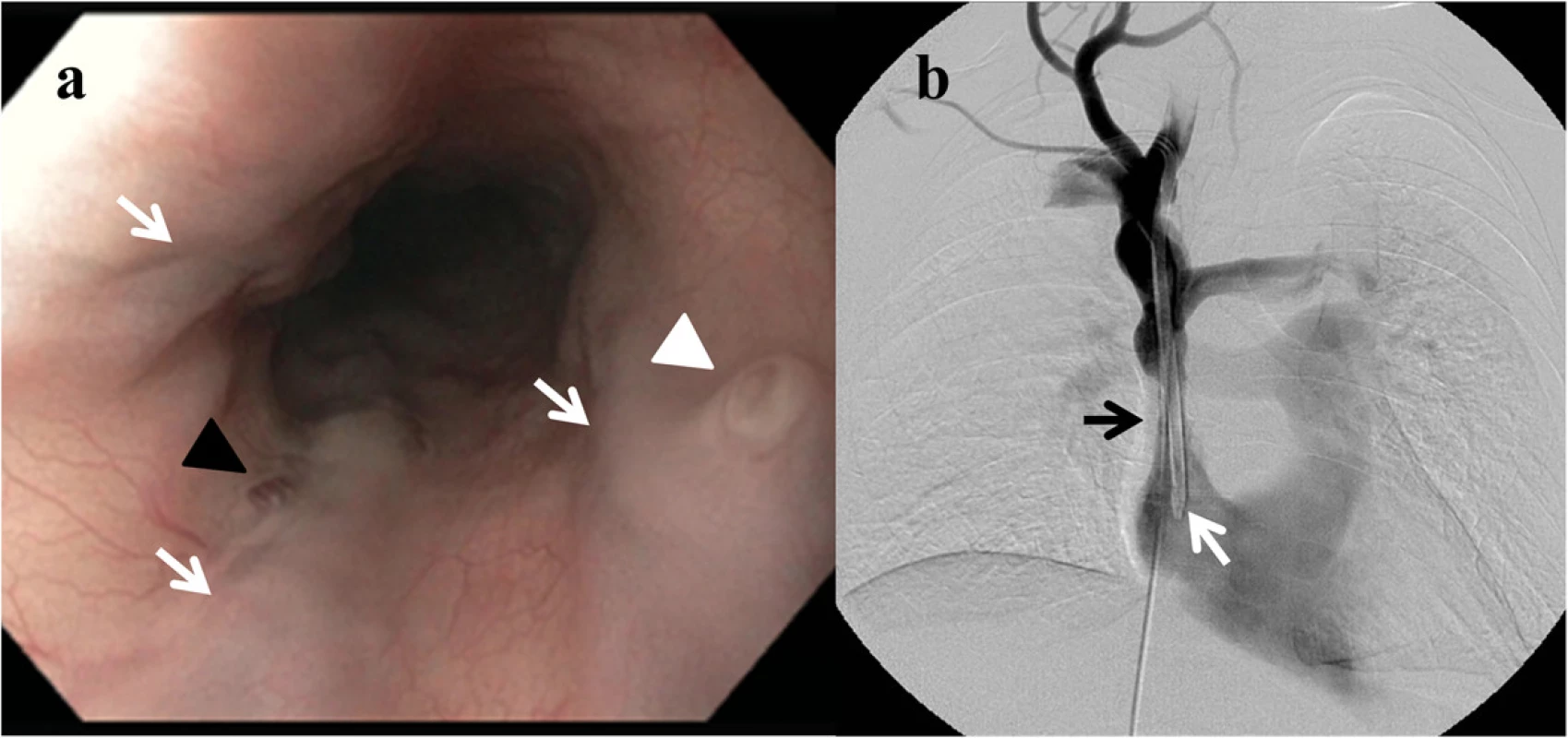

A 22 year-old woman presented with acute hematemesis, tachycardia, and hypotension after 3 days of melenic stools. Her only medical history was end-stage kidney disease due to Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and she underwent chronic hemodialysis using a tunneled right internal jugular venous catheter due to prior complications with her right arm fistula. Her current hemodialysis catheter had been in place for approximately 14 months. She had no history of prior liver disease or gastrointestinal bleeding and denied NSAID use. Physical exam was notable for facial edema and erythema (plethora), abdominal and chest wall varices, and tachycardia, without stigmata of chronic liver disease (ascites, splenomegaly, palmar erythema, or spider telangiectasias). Laboratory evaluation revealed an acute anemia (hemoglobin 4.65 mmol/L) with normal platelets, liver function, and coagulation studies. Upper endoscopy was urgently pursued and revealed three columns of large varices in the proximal esophagus with stigmata of recent hemorrhage (Fig. 1a) and a normal distal esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. CT angiogram showed a stenosis in the superior vena cava adjacent to the distal aspect of her hemodialysis catheter with a dilated azygous vein bypassing the stenotic SVC segment to supply the proximal esophageal varices in a retrograde direction.

Fig. 1. a Esophagogastroduodenoscopy in a patient with superior vena cava obstruction demonstrating varices in the proximal esophagus (white arrows), with overlying red wales (black arrowhead) and a fibrin plug (‘nipple sign’) (white arrowhead), indicating recent hemorrhage. b Venography of the superior vena cava showing a tunneled dialysis catheter (white arrow) with an adjacent superior vena cava stenosis (black arrow)

The patient experienced a second episode of hematemesis and urgently underwent balloon dilation of the stenotic SVC segment under angiography (Fig. 1b). She had no further episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding and her vital signs normalized immediately after the procedure. She was discharged shortly thereafter and underwent a repeat balloon dilation of the stenotic SVC segment 1 week after discharge. She did not experience recurrent gastrointestinal hemorrhage over a 12-month follow up period after her hospitalization.

Conclusions

Providers should be vigilant for bleeding “downhill” varices in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and clinical evidence of SVC obstruction because the pathophysiology of this disorder mandates a unique management compared to esophageal varices occurring in the usual setting of portal hypertension and cirrhosis. Though data is lacking, traditional medical management would be unlikely to be of benefit in this population. Octreotide, as a splanchnic dilator would not decrease the pressure in “downhill” varices as they do not communicate directly with the portal system. Proton pump inhibitors would be unlikely to play a role as the upper esophagus is less likely to be influenced by gastric pH. The current literature only provides guidance for therapy by means of case reports and while firm recommendations cannot be made as to ideal therapy in this patient population, several methods of temporization seem to have been successful in halting bleeding until definitive decompression of the affected vessels can be performed. Further investigation is required to determine why benign, as opposed to malignant, causes of SVC obstruction result in bleeding from downhill varices at such a high rate, despite being a less common etiology of SVC obstruction in the general population.

Abbreviations

DVT: Deep vein thrombosis; SVC: Superior vena cava; USA: United States of America

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

ML: drafting and editing of the manuscript. SA and BS: editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent, which is available on request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Received: 13 May 2016

Accepted: 18 October 2016

Published: 24 October 2016* Correspondence:

Michael Loudin

Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology

Oregon Health & Science University

3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road

Portland, OR L-461, USAloudin@ohsu.edu

Zdroje

1. Siegel Y, Schallert E, Kuker R. Downhill esophageal varices: a prevalent Backgroundcomplication of superior vena cava obstruction from benign and malignant causes. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2015;39(2): 149–52.

2. Areia M, Romaozinho JM, Ferreira M, Amaro P, Freitas D. “Downhill” varices. A rare cause of esophageal hemorrhage. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas : organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Patologia Digestiva. 2006;98(5):359–61.

3. Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine. 2006;85(1):37–42.

4. Pillai U, Roopkiranjot K, Lakshminarayan N, Balabhadrapatruni K, Gebregeorgis W, Kissner P. Downhill varices secondary to HeRO graftrelated SVC syndrome. Seminars in dialysis. 2013;26(5):E47–9.

5. Bedard EL, Deslauriers J. Bleeding “downhill” varices: a rare complication of intrathoracic goiter. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2006;81(1):358–60.

6. Froilan C, Adan L, Suarez JM, Gomez S, Hernandez L, Plaza R, et al. Therapeutic approach to “downhill” varices bleeding. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2008;68(5):1010–2.

7. Agarwal AK, Patel BM, Haddad NJ. Central vein stenosis: a nephrologist’s perspective. Seminars in dialysis. 2007;20(1):53–62.

8. Nayudu SK, Dev A, Kanneganti K. “Downhill” Esophageal Varices due to Dialysis Catheter-Induced Superior Vena Caval Occlusion: A Rare Cause of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Case reports in gastrointestinal medicine. 2013;2013 : 830796.

9. Vorlop E, Zaidman J, Moss SF. Clinical challenges and images in GI. Downhill esophageal varices secondary to superior vena cava occlusion. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(6):1863. 2158.

10. Hussein FA, Mawla N, Befeler AS, Martin KJ, Lentine KL. Formation of downhill esophageal varices as a rare but serious complication of hemodialysis access: a case report and comprehensive literature review. Clinical and experimental nephrology. 2008;12(5):407–15.

11. Greenwell MW, Basye SL, Dhawan SS, Parks FD, Acchiardo SR. Dialysis catheter-induced superior vena cava syndrome and downhill esophageal varices. Clinical nephrology. 2007;67(5):325–30.

12. Blam ME, Kobrin S, Siegelman ES, Scotiniotis IA. “Downhill” esophageal varices as an iatrogenic complication of upper extremity hemodialysis access. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2002;97(1):216–8.

13. Pop A, Cutler AF. Bleeding downhill esophageal varices: a complication of upper extremity hemodialysis access. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 1998;47(3): 299–303.

14. Gopaluni S, Warwicker P. Superior vena cava obstruction presenting with epistaxis, haemoptysis and gastro-intestinal haemorrhage in two men receiving haemodialysis with central venous catheters: two case reports. Journal of medical case reports. 2009;3 : 6180.

15. Pashankar D, Jamieson DH, Israel DM. Downhill esophageal varices. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 1999;29(3):360–2.

16. Mikkelson W. Varices of the upper esophagus in superior vena caval obstruction. Radiology. 1963;81 : 945–8.

17. Savoy AD, Wolfsen HC, Paz-Fumagalli R, Raimondo M. Endoscopic therapy for bleeding proximal esophageal varices: a case report. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2004;59(2):310–3.

18. Sundermann A. Retrosternale struma and osophagusvarizen. Munchen Med Wehschr. 1960;102 : 2133–6.

19. Johnson LS, Kinnear DG, Brown RA, Mulder DS. ‘Downhill’ esophageal varices. A rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill: 1960). 1978;113(12):1463–4.

20. Yasar B, Abut E. A case of mediastinal fibrosis due to radiotherapy and ‘downhill’ esophageal varices: a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clinical journal of gastroenterology. 2015;8(2):73–6.

21. Basaranoglu M, Ozdemir S, Celik AF, Senturk H, Akin P. A case of fibrosing mediastinitis with obstruction of superior vena cava and downhill esophageal varices: a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 1999;28(3):268–70.

22. Glanz S, Koser MW, Dallemand S, Gordon DH, Marshak RH. Upper esophageal varices: report of three cases and review of the literature. The American journal of gastroenterology. 1982;77 : 194–8.

23. Pugliese FM. A surgical approach to bleeding downhill varices. Angiology. 1973;24(10):606–11.

24. Snodgrass RW, Mellinkoff SM. Bleeding varices in the upper esophagus due to obstruction of the superior vena cava. Gastroenterology. 1961; 41 : 505–8.

25. Papazian A, Capron JP, Remond A, Descombes P, Ringot PL, Desablens B, et al. Upper esophageal varices. Study of 6 cases and review of the literature. Gastroenterologie clinique et biologique. 1983;7(11):903–10.

26. Palmer E. Primary varices of the cervical esophagus as a source of massive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Dig Dis. 1952;19 : 375–7.

27. Ibis M, Ucar E, Ertugrul I, Boyvat F, Basar O, Ataseven H, et al. Inferior thyroid artery embolization for downhill varices caused by a goiter. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2007;65(3):543–5.

28. Fleig WE, Stange EF, Ditschuneit H. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage from downhill esophageal varices. Digestive diseases and sciences. 1982;27(1):23–7.

29. Kelly TR, Mayors DJ, Boutsicaris PS. “Downhill” varices; a cause of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The American surgeon. 1982;48(1):35–8.

30. Tavakkoli H, Asadi M, Haghighi M, Esmaeili A. Therapeutic approach to “downhill” esophageal varices bleeding due to superior vena cava syndrome in Behcet’s disease: a case report. BMC gastroenterology. 2006;6 : 43.

31. Ichikawa M, Kobayashi H, Mukai M, Saitoh Y. Superior vena cava syndrome as initial symptom of Vasculo-Behcet’s disease—case report. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai zasshi. 1991;29(10):1344–8.

32. Calderwood AH, Mishkin DS. Downhill esophageal varices caused by catheter-related thrombosis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2008;6(1), e1.

33. Maton PN, Allison DJ, Chadwick VS. “Downhill” esophageal varices and occlusion of superior and inferior vena cavas due to a systemic venulitis. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 1985;7(4):331–7.

34. Tincani E, Criscuolo C, Zenesini A, Bondi M. An unusual site of bleeding from esophageal varices. Recenti progressi in medicina. 1998;89(6):301–3.

35. Malloy L, Jensen M, Bishop W, Divekar A. “Downhill” esophageal varices in congenital heart disease. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2013;56(2):e9–11.

36. Tsokos M, Bartel A, Schoel R, Rabenhorst G, Schwerk WB. Fatal pulmonary embolism after endoscopic embolization of downhill esophageal varix. Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift (1946). 1998;123(22):691–5.

37. Martorell F. Varices del esophago por hipertension caval superior. Angiologia. 1955;7 : 49–53.

Štítky

Gastroenterologie a hepatologie

Článek vyšel v časopiseBMC Gastroenterology

Nejčtenější tento týden

2016 Číslo 134- Horní limit denní dávky vitaminu D: Jaké množství je ještě bezpečné?

- Nejlepší kůže je zdravá kůže: 3 úrovně ochrany v moderní péči o stomii

- Ferinject: správně indikovat, správně podat, správně vykázat

- Cinitaprid – v Česku nová účinná látka nejen pro léčbu dysmotilitní dyspepsie

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání