-

Medical journals

- Career

Hiátová hernie a Barrettův ezophagus, četnost výskytu příznaků poruchy a komplikací

Authors: M. Al-Tashi 1; S. Rejchrt 1; M. Kopáčová 1; V. Tyčová 2; M. Široký 1; R. Repák 1; I. Tachecí 1; T. Douda 1; J. Cyrany 1; T. Fejfar 1; P. Hůlek 1; J. Bukač 3; J. Bureš 1

Authors‘ workplace: Charles University in Praha, nd Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine at Hradec Králové, University Teaching Hospital, Hradec Králové 1; Charles University in Praha, The Fingerland Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine at Hradec Králové, University Teaching Hospital, Hradec Králové 2; Charles University in Praha, Department of Medical Biophysics, Faculty of Medicine at Hradec Králové 3

Published in: Čas. Lék. čes. 2008; 147: 564-568

Category: Original Article

Overview

Cílem studie bylo hodnocení vlivu skluzné hiátové hernie na Barrettův ezophagus včetně výskytu jednotlivých příznaků a komplikací.

Metody.

Celkem bylo zapracováno 520 (4,6 %) případů Barrettova ezophagu diagnostikovaného při 18 276 horních gastrointestinálních endoskopiích, provedených u 11 276 pacientů v jednom terciární centru v letech 1994–2004.Výsledky.

Skluzná hiátová hernie byla nalezena u 58 % pacientů s Barrettovým ezophagem; častější výskyt byl u mužů (60 %). Souvislost mezi hernií a komplikacemi Barrettova ezophagu byla významná (94 % Barrettův vřed, 77 % low-grade dysplasie při p < 0,01). Nebyla však prokázána souvislost s adenokarcinomem (54 %; p > 0,05). Další komplikace Barrettova ezophagu (např. krvácení stenóza, high-grade dysplasia) byly diagnostikovány jen zřídka (méně než 10), takže nebyly statisticky vyhodnocovány. Souvislost mezi přítomností hiátové hernie a výskytem příznaků refluxu (dysfagie, odynofagie, dyspeptické a další příznaky) byla významná při p < 0,01.Závěry.

Studie ukazuje, že skluzná hiátová hernie může být významným patofyziologickým faktorem Barrettova ezophagu. Četnost komplikací Barrettova ezophagu není u jednotlivých případů stejná, zvláště u případů s hiátovou hernií. Výskyt příznaků je častější u pacientů se skluznou hiátovou hernií.Klíčová slova:

Barrettův ezophagus, skluzná hiátová hernie, příznaky, komplikace.A sliding hiatal hernia disrupts both the anatomy and physiology of the normal antireflux mechanism. It reduces lower oesophageal sphincter length and pressure, and impairs the augmenting effects of the diaphragmatic crura. It is associated with decreased oesophageal peristalsis, increases the cross-sectional area of the oesophago-gastric junction, and acts as a reservoir allowing reflux from the hernia sac into the oesophagus during swallowing. The overall effect is that of increased oesophageal acid and/or bile exposure. The presence of hiatal hernia is associated with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux, increased prevalence and severity of reflux oesophagitis, as well as Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Barrett’s oesophagus is defined as a change in the oesophageal epithelium of any length that can be recognized at endoscopy and is confirmed to have incomplete intestinal metaplasia (colonic type) by biopsy of the tubular oesophagus and excludes intestinal metaplasia of the cardia (1, 2).

It is generally accepted that approximately 10% of patients with chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease will be diagnosed with this condition (3). It has been proposed that sliding hiatal hernia is a risk factor for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and its complications, particularly Barrett’s oesophagus. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of sliding hiatal hernia in Barrett’s oesophagus and its impact on symptoms rate and complications in patients of a single tertiary centre.

Patients and methods

A total of 520 (4.6%) cases of Barrett’s oesophagus were found out of 18.276 upper gastrointestinal endoscopies, performed in 11.276 patients at a single tertiary centre from 1994 to 2004. This cohort was evaluated retrospectively. However, endoscopies were recorded and biopsy specimens were archived so that it was possible to re-check and/or re-evaluate particular cases if needed. The presence or absence of histological confirmation of Barrett’s oesophagus, correlation with possible risk factors (i.e. sliding hiatal hernia, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, NSAIDs abuse, Helicobacter pylori infection and obesity) were studied. The complications of Barrett’s oesophagus (ulcer, bleeding, stenosis, low - or high-grade dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma) and the clinical features (reflux and dyspeptic symptoms) were noted. The distribution of Barrett’s oesophagus by age and gender was also assessed in this analysis.

Data were treated statistically by means of the NCSS programme. We used descriptive statistics, t-test, Mann-Whitney test, Chi-square test and Fisher’s test. The association between the presence of sliding hiatal hernia and Barrett’s oesophagus complications was examined on contingency tables. Because of great number of patients, the significance level was chosen at alfa = 0.01.

Results

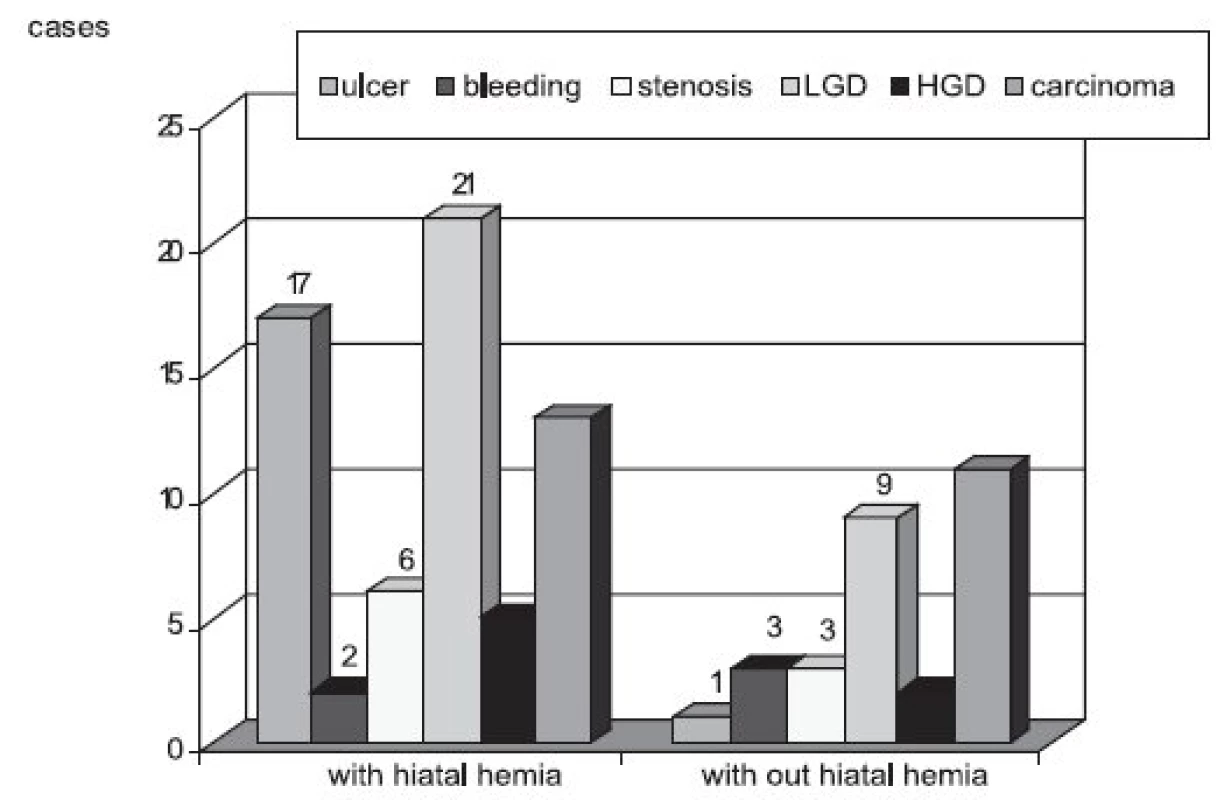

Out of 520 patients with endoscopical finding of Barrett’s oesophagus, 259 (50%) had a histological verification of incomplete intestinal metaplasia and 261 (50%) revealed negative histology. Hiatal hernia was confirmed endoscopically in 301 (58%) of cases. Sliding hiatal hernia was found in 60% of 348 men and 55% of 172 women. Hiatal hernia was found in 80% of 57 cases with “classic” Barrett’s oesophagus (long segment, histologically verified) and in 63% of all 259 histologically verified (both long and short segments). The association between hernia and some complications of Barrett’s oesophagus was significant (94% of Barrett’s ulcer, 77% of low-grade dysplasia; p < 0.01), but not significant with oesophageal adenocarcinoma (54%; p > 0.05. The other complications of Barrett’s oesophagus (i.e. bleeding, stenosis, high-grade dysplasia) were identified in small number (less than 10 cases) so were not statistically evaluated. The association between presence of hiatal hernia and occurrence of symptoms (reflux symptoms, dysphagia, odynophagia, dyspeptic and other symptoms) was significant with p < 0.01 (see Fig. 1 for details).

Image 1. Barrett’s oesophagus: complication with and without hiatal hernia

Possible risk factors (alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, obesity, NSAIDs abuse and presence/absence of Helicobacter pylori infection) for Barrett’s oesophagus confirmation were found in different significance. As a risk factor in our set of patients we found alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking and obesity (p < 0.01). Helicobacter pylori infection or NSAIDs abuse were not found as a risk factor for Barrett’s oesophagus (p > 0.05).

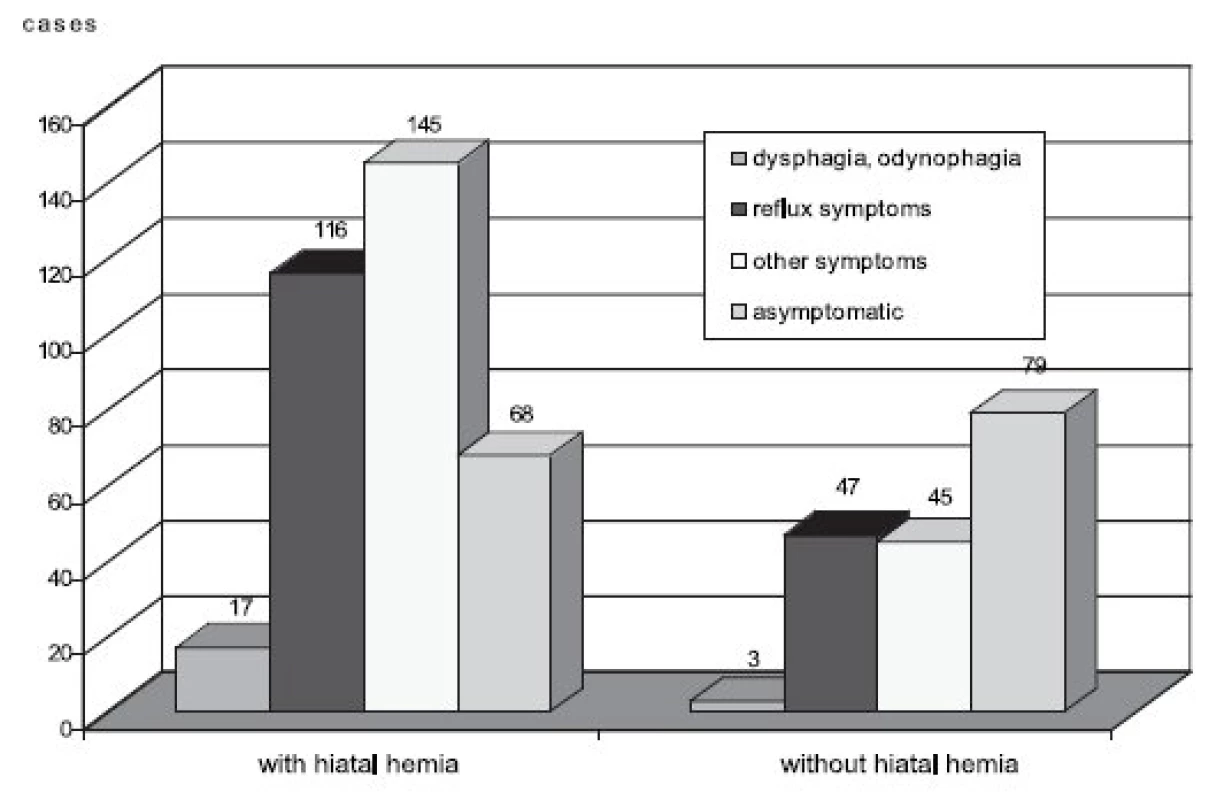

Out of 163 patients complaining of reflux symptoms (heart burn, regurgitation) 71% had sliding hiatal hernia. Due to dysphagia or odynophagia 20 patients were investigated, 85% of them had sliding hiatal hernia. Dyspeptic and some other symptoms annoyed 190 patients, 76% of them had sliding hiatal hernia. The association between symptoms occurrence and sliding hiatal hernia was statistically significant (p < 0.01). Asymptomatic patients with sliding hiatal hernia were found less frequently (46%) compared to those without hiatal hernia (54%) though this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 2).

Image 2. Sliding hiatal hernia and presence of clinical symptoms

Discussion

Hiatal hernia refers to the herniation of parts of the abdominal contents through the oesophageal hiatus of the diaphragm. The most comprehensive classification scheme recognizes four types of hiatal hernia (4–6). Type I sliding hiatal herniathe commonest type, para-oesophageal hernias (types II to IV) are less common types of hiatal hernia, which account for up to 5% (6, 7). The factors governing the acquisition of specialized intestinal metaplasia and the pathological phenotype of Barrett’s oesophagus are probably multi-factorial but the clearest pathophysiological association is with long-standing severe gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (8, 9). The changes in Barrett’s oesophagus are characterized by increased frequency and duration of oesophageal acid exposure, increased bile reflux, decreased lower oesophageal sphincter pressure, and delayed oesophageal clearance compared to patients who have severe oesophagitis in absence of Barrett’s epithelium (10, 11).

The histological verification of Barrett’s oesophagus depends on the number of biopsy specimens taken at endoscopy (12). One previous study verified that number of specimens was significantly less in cases of Barrett’s oesophagus suspected at endoscopy but not verified at histology. However complications including adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus were found within both types, thus endoscopic finding should be considered as determining (13). That is why in our present study we analyzed also cases of hiatal hernia within the suspected Barrett’s oesophagus (typical endoscopic appearance without histological verification).

Hiatal hernia advance the reflux thereby: first, hiatal hernia impairs the clearance of acid from the oesophagus (14, 15), second, it acts as a reservoir from which acid readily refluxes into the oesophagus during swallowing-induced relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter (16), third, a large hiatal hernia causes a widening of the oesophageal hiatus that may impair the ability of the crural diaphragm to function as a sphincter (17). One ex-vivo study presents that continuous acid exposure blocked cell proliferation in Barrett’s oesophagus, whereas an acid-pulse enhanced cell proliferation as compared to pH 7.4 (18). According to another study (19) the length of Barrett’s mucosa correlated with the duration of oesophageal acid exposure. Duration of oesophageal acid exposure appears to be an important contributing factor in determining the length of Barrett’s mucosa.

The prevalence of sliding hiatal hernia varies from place to place with normal population. High frequency of hiatal hernia has been reported in several studies in Western general population. For example 16.6% of 670 subjects (Norway) (20),22% of 293 subjects (USA) (21), 16.6% of 1000 subjects in Prague (22) and 14.5% of 1000 subjects (Sweden) (23) undergoing upper endoscopy were found to have a sliding hiatal hernia. We found 248 patients (25%) with hiatal hernia in a non-selected group of 999 subjects that underwent upper GI endoscopy at our endoscopic unit during the first half of year 2004.

In present study, sliding hiatal hernia was clearly verified in a great percentage of patients with a long segment of Barrett’s oesophagus (80%) and in 55% of patients with a short segment. Cameron et al. in their study on prevalence and size of hiatal hernia within Barrett’s oesophagus found even greater presence of hiatal hernia than we did: 96% of patients with long segment of Barrett’s oesophagus, and in 72% of patients with short segment of Barrett’s oesophagus (24). The role of sliding hiatal hernia in the developing of Barrett’s oesophagus and some of its complications is understood in our study, because of high existence of it with our studied patients. The finding of hiatal hernia in different studies has a statistically significant high risk for a development of dysplasia and oesophageal adenocarcinoma as a complication of Barrett’s oesophagus (24–26). Our study whoever did not support this suggestion. The role of other risk factors in Barrett’s oesophagus formation as alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking or obesity was verified by our study as well by several other studies (26, 27). According to other studies, there is a suggestion that patients with sliding hiatal hernia have heart burn and gastro-oesophageal regurgitation several times more frequently than patients without hernia, even in absence of oesophagitis and they are less sensitive to anti-secretory therapy (28, 29). Asymptomatic patients with Barrett’s oesophagus are reported in about 25% (30), in our study the rate is nearly the same (28%).

Conclusions

Sliding hiatal hernia is a major risk factor for development of Barrett’s oesophagus. Hiatal hernia is a predictive factor for the presence of gastro-oesophageal reflux and other symptoms in cases with Barrett’s oesophagus.

The study was supported by the research project MZO 00179906 from the Ministry of Health, Czech Republic.

Mohamed Al-Tashi, MD

2nd Department of Internal Medicine, University Teaching Hospital

Sokolská 581, 500 05 Hradec Králové

e-mail: altashi@seznam.cz

Sources

1. Sampliner, R. E: Practice Updated guidelines for the diagnosis, surveillance, and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 2002, 97, s. 1888–1895.

2. Lukáš, K., Bureš, J., Drahoňovský, V. et al.: Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Guidelines of the Czech Society of Gastroenterology (in Czech). Čes. Slov. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 2003, 57, s. 23–29.

3. Sharma, P.: Prevalence of Barrett’s oesophagus and metaplasia at the gastro-oesophageal junction. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 20 (Suppl 5), s. 48-54.

4. Dodds, W. J., Walter, B.: Cannon Lecture: Current concepts of esophageal motor function: clinical implications for radiology. Am. J. Roentgenol., 1977, 128, s. 549–561.

5. Mittal, R. K.: Hiatal hernia: myth or reality? Am. J. Med., 1997, 103, s. 33S–39S.

6. Kahrilas, P. J.: Hiatus hernia. UpToDate 2008, vol 16.2.

7. Kahrilas, P. J.: Hiatus hernia causes reflux: Fact or fiction? Gullet, 1993, 3 (Suppl.), s. 21.

8. Spechler, S. J.: Barrett’s esophagus. N. Engl. J. Med., 2002, 346, s. 836–842.

9. Stein, H. J, Hoeft, S, DeMeester, T. R.: Reflux and motility patterns in Barrett’s esophagus. Dis. Esophagus, 1992, 5, s. 21–28.

10. Gillen, P., Keeling, P., Byrne, P. J., Hennessy, T. P. J.: Barrett’s esophagus: pH profile. Br. J. Surg., 1987, 74, s. 774–776.

11. Campos, G. M., DeMeester, T. R., Peters, J. H. et al.: Predictive factors of Barrett’s esophagus: multivariate analysis of 502 patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arch. Surg., 2001, 136, s. 1267–1273.

12. Weinstein, W., Leh, W., Lewin, K. et al.: How often is short segment Barrett’s esophagus proven histologically? A prospective study. Gastroenterology, 2002, 122 (Suppl.), s. A293.

13. Al-Tashi, M., Bureš, J., Rejchrt, S. et al.: Barrett’s oesophagus: prevalence and complications of disease between 1994 and 2003 (in Czech). Čes. Slov. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 2005, 59, s. 62–65.

14. Mittal, R. K., Lange, R. C., McCallum, R. W.: Identification and mechanism of delayed acid clearance in subjects with hiatus hernia. Gastroenterology, 1987, 92, s. 130–135.

15. Sloan, S., Kahrilas, P. J.: Impairment of esophageal emptying with hiatal hernia. Gastroenterology, 1991, 100, s. 596-605.

16. Mittal, R. K., Balaban, D. H.: The esophagogastric junction. N. Engl. J. Med., 1997, 336, s. 924–932.

17. Sloan, S., Rademaker, A. W., Kahrilas, P. J.: Determinants of gastroesophageal junction incompetence: hiatal hernia, lower esophageal sphincter, or both? Ann. Intern. Med., 1992, 117, s. 977–982.

18. Fitzgerald, R. C., Omary, M. B., Triadafilopoulos, G.: Dynamic effects of acid on Barrett’s esophagus. An ex vivo proliferation and differentiation model. J. Clin. Invest., 1996, 98, s. 2120.

19. Fass, R., Hell, R. W., Garewal, H. S. et al.: Correlation of oesophageal acid exposure with Barrett’s oesophagus length. Gut, 2001, 48, s. 310.

20. Berstad, A., Weberg, R., Larsen, I. F. et al.: Relationship of hiatus hernia to reflux oesophagitis. A prospective study of coincidence, using endoscopy. Scand. J. Gastroenterol., 1986, 21, s. 55–58.

21. Wright, R. A., Hurwitz, A. L.: Relationship of hiatal hernia to endoscopy proven esophagitis. Dig. Dis. Sci., 1979, 24, s. 311–313.

22. Ténaiová, J., Tůma, L., Hrubant, K. et al.: Incidence of hiatal hernias in the current endoscopic praxis (in Czech). Čas. Lék. čes., 2007, 146, s. 74–76.

23. Cronstedt, J., Carling, L., Vestergaard, P., Berglund, J.: Oesophageal disease revealed by endoscopy in 1000 patients referred primarily for gastroscopy. Acta Med. Scand., 1978, 204, s. 413–416.

24. Cameron, A. J.: Barrett’s esophagus: prevalence and size of hiatal hernia. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 1999, 94, s. 2054–2059.

25. Patti, M. G., Goldberg, H. I., Arcerito, M. et al.: Hiatal hernia size affects lower esophageal sphincter function, esophageal acid exposure, and the degree of mucosal injury. Am. J. Surg., 1996, 171, s. 182–186.

26. Avidan, B., Sonnenberg, A., Schnell, T. G. et al.: Hiatal hernia size, Barrett’s length, and severity of acid reflux are all risk factors for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 2002, 97, s. 1930–1936.

27. Avidan, B., Sonnenberg, A., Schnell, T. G., Sontag, S. J.: Hiatal hernia and acid reflux frequency predict presence and length of Barrett’s esophagus. Dig. Dis. Sci., 2002, 47, s. 256–264.

28. Frazzoni, M., De Micheli, E., Grisendi, A., Savarino, V.: Hiatal hernia is the key factor determining the lansoprazole dosage required for effective intra-oesophageal acid suppression. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther., 2002, 16, s. 881–886.

29. Petersen, H., Johannessen, T., Sandvik, A. K. et al.: Relationship between endoscopic hiatus hernia and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Scand. J. Gastroenterol., 1991, 26, s. 921–926.

30. Gerson, L. B., Schetler, K., Triadafilopoulos, G.: Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in asymptomatic individuals. Gastroenterology, 2002, 123, s. 461–467.

Labels

Addictology Allergology and clinical immunology Angiology Audiology Clinical biochemistry Dermatology & STDs Paediatric gastroenterology Paediatric surgery Paediatric cardiology Paediatric neurology Paediatric ENT Paediatric psychiatry Paediatric rheumatology Diabetology Pharmacy Vascular surgery Pain management Dental Hygienist

Article was published inJournal of Czech Physicians

-

All articles in this issue

- Galektiny v dlaždicových karcinomech hlavy a krku

- Hiátová hernie a Barrettův ezophagus, četnost výskytu příznaků poruchy a komplikací

- Primárny B-bunkový non-Hodgkinov lymfóm Burkittovského typu: popis prípadu s typickými klinickými prejavy

- Patogeneticky komplikovaný případ osteoporózy u mladého muže

- Racionalita a iracionalita v medicíně a v životě

- Journal of Czech Physicians

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Galektiny v dlaždicových karcinomech hlavy a krku

- Racionalita a iracionalita v medicíně a v životě

- Hiátová hernie a Barrettův ezophagus, četnost výskytu příznaků poruchy a komplikací

- Primárny B-bunkový non-Hodgkinov lymfóm Burkittovského typu: popis prípadu s typickými klinickými prejavy

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career