-

Medical journals

- Career

ALBA and PICNIR tests used for simultaneous examination of two patients with dementia and their adult children

Authors: A. Bartoš

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Neurology, Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and Faculty Hospital Kralovske Vinohrady, Prague, Czech Republic

Published in: Cesk Slov Neurol N 2021; 84(6): 583-586

Category: Letters to Editor

doi: https://doi.org/10.48095/cccsnn2021583Dear editors,

This article reports about interesting experiences and findings obtained from a parallel examination of two patients with dementia and their adult children using two brief cognitive tests.

Some patients with dementia are children of their parents who were affected with cognitive disorders before death. Analogically, adult children of patients with dementia may be at increased risk of developing cognitive disorders.

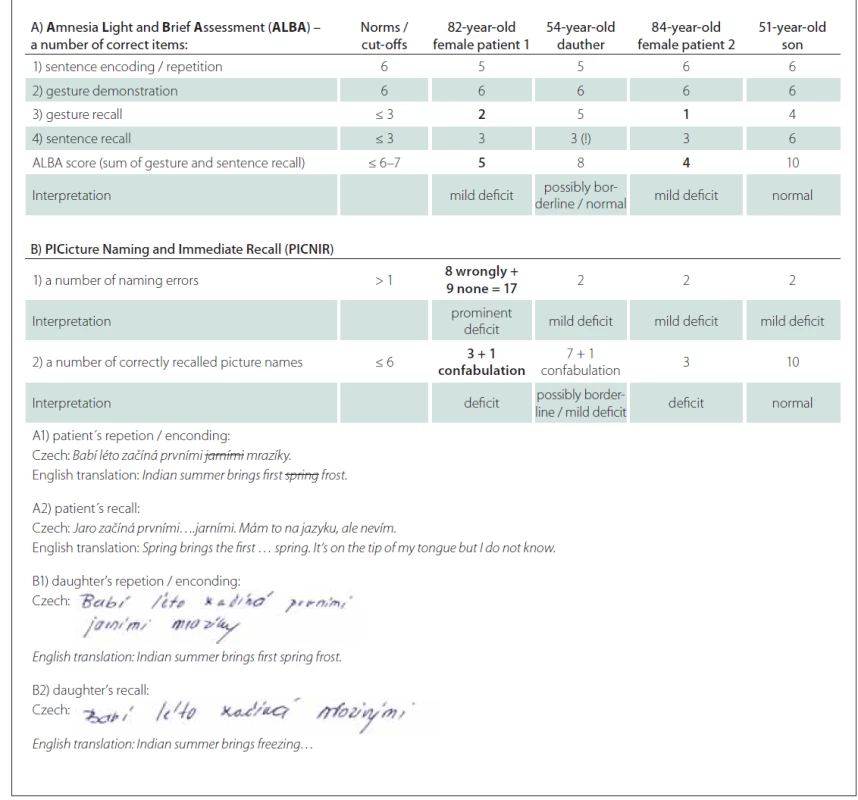

Recently, we developed and introduced innovative and original Czech tests known as the Amnesia Light and Brief Assessment (abbreviated as ALBA) and the Picture naming and immediate recall test (abbreviated as PICNIR). They are very brief taking up to five minutes to complete and measure deficits of more cognitive functions (short-term, episodic, semantic amnesia, sensory and motor aphasia, apraxia, psychomotor speed). Their thresholds were determined for the elderly within a main age range between 70-80 years in the first validation reports. Cut-offs of the ALBA test are ≤ 3 correctly recalled sentence words, ≤ 3 correctly recalled gestures, and ≤ 6 or 7 points on the ALBA score. Cutoff points of the PICNIR test are more than one mistake in picture naming and less than 6 correctly recalled picture names (Tab. 1) [1–4]. Instructional videos show administration and scoring on both tests and can be watched on YouTube on the Ales Bartos channel with English subtitles.

1. Results of patients with dementia and their off spings in the ALBA and the PICNIR compared with elderly norms.

ALBA sentence examples of couple 1 are in the lower part of Tab. 1.

Abnormal values are highlighted in bold.

It is unknown whether the ALBA and PICNIR tests can detect presumably subtle cognitive deficits in offspring that are one generation younger than their parent (s) with dementia. Additionally, it is unclear whether administration of both tests can be modified and performed in one room simultaneously in both the patient and patient’s child. This could assist in busy everyday examinations with limited time and rooms.

Therefore, the aim of this report is to share experiences and results with simultaneous testing of two patients with dementia and their adult children using ALBA and PICNIR. The first 82-year-old female was accompanied by a 54-year-old daughter with 17 years of university education and the second 84-year-old female came with a 51-year-old son. A neurodegenerative process combined with vascular changes of the patient´s brain is assumed. It is based on worsening in the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and neuroimaging changes. She deteriorated from the MMSE score of 27 points at regional setting to 17 points at our memory center over fivesix years. Her brain MRI showed confluent white matter changes and borderline sizes of the hippocampi (Hipocampo-horn percentage (Hip-hop) right 60% / left 75%). Asymmetric parieto-temporal and left occipital and temporopolar hypoperfusion were present on her brain single photon emission tomography (SPECT). DatScan was normal. Her daughter accepted brain SPECT which detected mild perfusion changes at a right frontolateral region and bilateral posterotemporal and occipital regions.

The second 84-year-old patient came with a 51-year-old son who had 17 years of university education. The patient scored 75 (16 + 16 + 5 + 24 + 14) points in the Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination, 23 points in the MMSE and 3 (2 + 1) points in the Mini-Cog. Mild brain atrophy, borderline hippocampal size (Hip-hop right 60% / left 70%) and mild vascular changes (Fazekas 2) were present on brain MRI. Her brain SPECT was almost normal, only subtle biparietal hypoperfusion was detected. Her son was not further examined due to mild changes of her mother´s brain and normal ALBA and PICNIR testing except two errors in picture naming.

Administration of both tests was performed as follows. An experienced nurse gave initial instructions for each test both to the patient and to the offspring. Then, she continued testing with the patient while a neurologist and an author of this article completed testing with the patient’s offspring in the same room at the same time.

Two patients with dementia were examined and scored as described previously [1–4]. A new version of the door PICNIR was used [5]. It is almost an ideal test for parallel examination since picture naming and recall are self-written and silent tasks [3–5]. Unlike the standard administration of the ALBA, each patient’s child wrote sentences instead of saying them out loudly and silently recalled gestures and re-demonstrated as many gestures as possible in any order and without any accompanying verbal description of the gesture. The reason was not to disturb testing of the patient by the offspring’s speech.

Results of ALBA and PICNIR tests of both couples are summarized in Tab. 1. Both patients recalled less gestures and sentence words than the cut-offs. Interestingly, the first adult child recalled only three words which is a borderline number of sentence words in ALBA. In the PICNIR test, both patients made an increased number of picture naming errors and recalled only three picture names. This indicates cognitive impairment in agreement with their lower ALBA results. Two examples of the PICNIR completed by the first patient and her daughter are shown in Fig. 1. Note that patient 1 had a very high number of seventeen errors (eight wrongly named plus nine unnamed pictures) ! Surprisingly, both children aged over 50 years made two picture misnamings including semantic paragraphias (Tab. 1, Fig. 1).

1. Fig. 1. Completed forms of the PICNIR from an 82-year-old female patient with mild dementia (A) and her 54-year-old daughter (B). English translations are provided for patient´s naming. A daughter of patient 1 used a flower instead of a cloverleaf in picture 5 and a ballooninstead of a parachute in picture 20. The other pictures were named correctly. The forms of the second couple are not shown because of limited space. They are commented only. A son of patient 2 used a window instead of a door in picture 1 and a chess instead of a chessboard in picture 17. Then, adult children were also asked to correct themselves after PICNIR testing. The daughter corrected the flower (above picture 5). However, she named the parachute picture wrongly again, i.e., that it is flying airship (above picture 20). After being told that this is the parachute, she expressed that she imagined it differently. In addition, this daughter recalled only seven correct picture names plus one confabulation (an astronaut). The son corrected both his picture misnamings. He commented that the door picture could look like a window.

Note the same misnaming of picture 5 flower instead of cloverleaf both in the patient and her daughter. This picture and the last picture 20 were named as cloverleaf and parachute by 97% out of 5,290 common Czechs across the whole country with age ranging 11–90 years and education ranging 8–28 years [5].

PICNIR – PICture Naming and Immediate Recall test

Obr. 1. Vyplněný formulář testu POBAV od 82leté pacientky s mírnou demencí (A) a její 54leté dcery (B).Dcera první pacientky nazvala květinou pátý obrázek čtyřlístku a balónem dvacátý obrázek padáku. Ostatní obrázky byly pojmenovány správně. Formuláře druhého páru nejsou uvedeny kvůli omezenému prostoru. Jsou pouze komentované. Syn druhé pacientky nazval dveře na prvním obrázku oknem a pojmenoval obrázek 17 jako šachy místo šachovnice. Poté byly dospělé děti také požádány, aby se opravily po testu POBAV. Dcera opravila špatné pojmenování kytky (nad obrázkem 5). Obrázek padáku však opět pojmenovala špatně. Konkrétně uvedla, že je to létající vzducholoď (nad obrázkem 20). Když jí bylo sděleno, že je to padák, vyjádřila se, že si ho představuje jinak. Navíc si tato dcera vybavila pouze sedm správných názvů obrázků plus jednu konfabulaci (astronaut). Syn si opravil oba chybné názvy obrázků. Komentoval obrázek dveří, že by takto mohla vypadat okna.

Všimněte si stejného chybného pojmenování obrázku 5 květina místo čtyřlístku u pacientky i její dcery. Tento obrázek a poslední obrázek 20 označilo jako čtyřlístek a padák 97 % z 5 290 běžných Čechů z celé republiky ve věku 11–90 let se vzděláním 8–28 let [5].

POBAV – Pojmenování obrázků a jejich vybavení![Fig. 1. Completed forms of the PICNIR from an 82-year-old female patient with mild dementia (A) and her 54-year-old daughter (B). English translations are provided for patient´s naming. A daughter of patient 1 used a flower instead of a cloverleaf in picture 5 and a ballooninstead of a parachute in picture 20. The other pictures were named correctly. The forms of the second couple are not shown because of limited space. They are commented only. A son of patient 2 used a window instead of a door in picture 1 and a chess instead of a chessboard in picture 17. Then, adult children were also asked to correct themselves after PICNIR testing. The daughter corrected the flower (above picture 5). However, she named the parachute picture wrongly again, i.e., that it is flying airship (above picture 20). After being told that this is the parachute, she expressed that she imagined it differently. In addition, this daughter recalled only seven correct picture names plus one confabulation (an astronaut). The son corrected both his picture misnamings. He commented that the door picture could look like a window.<br> Note the same misnaming of picture 5 flower instead of cloverleaf both in the patient and her daughter. This picture and the last picture 20 were named as cloverleaf and parachute by 97% out of 5,290 common Czechs across the whole country with age ranging 11–90 years and education ranging 8–28 years [5].<br> PICNIR – PICture Naming and Immediate Recall test<br> Obr. 1. Vyplněný formulář testu POBAV od 82leté pacientky s mírnou demencí (A) a její 54leté dcery (B).Dcera první pacientky nazvala květinou pátý obrázek čtyřlístku a balónem dvacátý obrázek padáku. Ostatní obrázky byly pojmenovány správně. Formuláře druhého páru nejsou uvedeny kvůli omezenému prostoru. Jsou pouze komentované. Syn druhé pacientky nazval dveře na prvním obrázku oknem a pojmenoval obrázek 17 jako šachy místo šachovnice. Poté byly dospělé děti také požádány, aby se opravily po testu POBAV. Dcera opravila špatné pojmenování kytky (nad obrázkem 5). Obrázek padáku však opět pojmenovala špatně. Konkrétně uvedla, že je to létající vzducholoď (nad obrázkem 20). Když jí bylo sděleno, že je to padák, vyjádřila se, že si ho představuje jinak. Navíc si tato dcera vybavila pouze sedm správných názvů obrázků plus jednu konfabulaci (astronaut). Syn si opravil oba chybné názvy obrázků. Komentoval obrázek dveří, že by takto mohla vypadat okna.<br> Všimněte si stejného chybného pojmenování obrázku 5 květina místo čtyřlístku u pacientky i její dcery. Tento obrázek a poslední obrázek 20 označilo jako čtyřlístek a padák 97 % z 5 290 běžných Čechů z celé republiky ve věku 11–90 let se vzděláním 8–28 let [5].<br> POBAV – Pojmenování obrázků a jejich vybavení](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image/972500fb6d77a1ecb792a842d24edae5.png)

What does this new approach indicate?

Firstly, it indicates that the ALBA and the PICNIR can be performed in parallel both in patients with cognitive disorders and their children. They may be carried out during routine clinical practice in view of limited rooms to save time. Obviously, the PICNIR is appropriately suitable for such a purpose. The instructions are stated only at the beginning followed by silent testing without interpersonal interference. Simultaneous ALBA testing is also feasible with some adjustments. If time or spare room are available, classic administration in separate examinations would be more appropriate.

Secondly, subtle cognitive changes in children older than 50 years may be detected with quick and simple yet challenging instruments such as the ALBA and the PICNIR. They take three and five minutes only respectively. Note the two misnamings in PICNIR in both children and borderline recall of the ALBA sentence and the PICNIR picture names in the daughter. As a reminder, she completed university studies and 17 years of education. Yet, she had three borderline results. However, they are related to value findings observed in older generation. It may be assumed that at least some scores of her performance would be under normal limits for her younger age.

Thirdly, questionable and possible subtle deficits in the daughter mean that such changes start decades before fully-developed dementia like in her mother. She agreed with long-term follow-up to see the final outcome and to undergo single brain photon emission tomography to determine whether neurobiological markers can also be detected.

All these experiences and findings are encouraging and have several impacts. It sounds appealing to screen and possibly detect cognitive changes by decades using brief and inexpensive tests instead of costly imaging, cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers or genetic testing. It is worth investigating more offsprings using the ALBA and the PICNIR in a more systematic way. Based on these two example cases it may be assumed that one part of children will have normal results while another part of them may not. However, this hypothesis should be verified in future. It will also bring several ethical issues whether such children want to know their current cognitive status, possible deficits and future fate. Observations with these two cases also open need for normative values of both ALBA and PICNIR tests in adults between 45–65 years who are younger than our previous normative sample. Moreover, they need to have clear negative family history of cognitive disorders.

Subtle cognitive changes in older adults may be accompanied by cerebrospinal fluid alterations and may develop into different dementias [6–8]. Such an early detection enables preventive measurements and identification of factors influencing the quality of life [9,10].

Overall, cognitive functions of patients with dementia and their children can be tested in parallel in one room. Subtle changes may be detected using very brief ALBA and PICNIR tests. This may indicate an emerging disease. A larger sample, norms for younger elderly and a long follow-up of these children would be useful.

Ethical principles

The entire study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (as revised in 2004 and 2008). All four persons signed informed consent forms to participate in our study on the mental and physical performance in seniors, which was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Kralovske Vinohrady under No EK-VP/54/0/2020 on the 2nd of September, 2020.

Financial support

This paper was supported by the Charles University project PROGRES Q 35 and Ministry of Health grants NV18-07-00272 and NV19-04-00090. All rights reserved.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study. An author is a developer of the ALBA and PICNIR tests.

The Editorial Board declares that the manu script met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

Redakční rada potvrzuje, že rukopis práce splnil ICMJE kritéria pro publikace zasílané do biomedicínských časopisů.Prof. Aleš Bartoš, MD, PhD

Department of Neurology

Third Faculty of Medicine

Charles University

Faculty Hospital Kralovske

Vinohrady

Ruská 2411/87

100 00 Prague

Czech Republic

e-mail: ales.bartos@fnkv.czAccepted for review: 24. 7. 2021

Accepted for print: 25. 11. 2021An extended version of this article can be found at csnn.eu.

Sources

1. Bartoš A. Dvě původní české zkoušky k vyšetření paměti za tři minuty – Amnesia Light and Brief Assessment (ALBA). Cesk Slov Neurol N 2019; 82/115 (4): 420–429. doi: 10.14735/amcsnn2019420.

2. Bartoš A, Diondet S. Test Amnesia Light and Brief Assessment (ALBA) – druhá verze a opakovaná vyšetření. Cesk Slov Neurol N 2020; 83/116 (5): 535–543. doi: 10.14735/amcsnn2020535.

3. Bartoš A. Pamatujte na POBAV – krátký test pojmenování obrázků a jejich vybavení sloužící ke včasnému záchytu kognitivních poruch. Neurol Praxi 2018; 19 (Suppl.1): 5–10.

4. Bartoš A. Netestuj, ale POBAV – písemné záměrné Pojmenování OBrázků A jejich Vybavení jako krátká kognitivní zkouška. Cesk Slov Neurol N 2016; 79/112 (6): 671–679.

5. Bartoš A, Polanská H. Správná a chybná pojmenování obrázků pro náročnější test písemného Pojmenování obrázků a jejich vybavení (dveřní POBAV). Cesk Slov Neurol N 2021; 84/117 (2): 151–163. doi: 10.48095/cccsnn2021151.

6. Bartoš A, Smětáková M, Říčný J et al. Možnosti stanovení likvorového tripletu tau proteinů a β-amyloidu 42 metodami ELISA a orientační normativní vodítka. Cesk Slov Neurol N 2019; 82/115(5): 533–540. doi: 10.14735/amcsnn2019533.

7. Bartošová T, Klempíř J. Progresivní supranukleární obrna. Cesk Slov Neurol N 2020; 83/116(6): 584–601. doi: 10.48095/cccsnn2020584.

8. Rusina R, Matěj R, Cséfalvay Z et al. Frontotemporální demence. Cesk Slov Neurol N 2021; 84/ 117(1): 9–29. doi: 10.48095/ cccsnn20219.

9. Janoutová J, Kovalová M, Ambroz P et al. Možnosti prevence Alzheimerovy choroby. Cesk Slov Neurol N 2020; 83/116(1): 28–32. doi: 10.14735/amcsnn202028.

10. Kisvetrová H, Školoudík D, Herzig R et al. Vliv demence na trajektorie kvality života seniorů. Cesk Slov Neurol N 2020; 83/116(3): 298–304. doi: 10.14735/ amcsnn2020298.

Labels

Paediatric neurology Neurosurgery Neurology

Article was published inCzech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

2021 Issue 6-

All articles in this issue

- Normotenzní hydrocefalus

- Synukleinopatie a jejich laboratorní biomarkery

- Klinicko-radiologický paradox u roztroušené sklerózy – význam vyšetření míchy

- Perorální kladribin v léčbě roztroušené sklerózy – data z celostátního registru ReMuS®

- Protein S 100B a jeho prognostické možnosti u kraniocerebrálních traumat

- Nodo-paranodopatie s protilátkami IgG4 proti neurofascinu-155

- Stiff -person syndrom

- Bilaterální paréza hlasivek v rámci recidivujících ischemických cévních mozkových příhod

- Guillain-Barrého syndrom u pacienta s COVID-19

- Obstrukční spánková apnoe u revmatoidního postižení subaxiální krční páteře

- Interpretace plazmatických hladin fenytoinu a valproátu při enterálním podávání u hypoalbuminemické pacientky

- Informace vedoucího redaktora

- Diferenciální diagnostika glioblastomu a solitárních metastáz mozku – úspěch modelů umělé inteligence vytvořených na základě radiomických dat získaných automatickou segmentací z konvenčních MR sekvencí

- Zobrazení průtoku mozkomíšního moku jednou sekvencí – variable flip angle turbo spin echo

- Aseptická meningitida při akutní hepatitidě E – zkušenosti z jednoho centra

- Rozsáhlé mnohočetné intraneurální gangliony peroneálního nervu

- Syndrom spinální sulkální arterie po stentem asistované embolizaci neprasklého aneuryzmatu vertebrální tepny embolizačním koilem

- Trombóza horní orbitální žíly

- ALBA and PICNIR tests used for simultaneous examination of two patients with dementia and their adult children

- Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Stiff -person syndrom

- Normotenzní hydrocefalus

- Synukleinopatie a jejich laboratorní biomarkery

- Perorální kladribin v léčbě roztroušené sklerózy – data z celostátního registru ReMuS®

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career