-

Medical journals

- Career

Srovnávací studie pacientů s myastenií České a Slovenské republiky

Authors: M. Horáková 1; I. Martinka 2; S. Voháňka 3; P. Špalek 2; J. Bednařík 3

Published in: Cesk Slov Neurol N 2019; 82(2): 171-175

Category: Original Paper

doi: https://doi.org/10.14735/amcsnn2019171Overview

Cíl: Stávající epidemiologické studie vykazují rozdíly v incidenci, prevalenci, incidenci specifické dle věku a pohlaví pacientů, mortalitě, a dokonce i v prevalenci jednotlivých subtypů myastenie. Cílem této studie bylo porovnat celkovou péči o pacienty s myastenií, závažnost onemocnění, celou řadu klinických a laboratorních charakteristik a terapeutický přístup mezi pacienty v České a Slovenské republice.

Soubor a metody: Data byla hodnocena retrospektivně ze dvou registrů v České republice (Brno) a Slovenské republice (Bratislava). Pacienti byly náhodně spárováni dle pohlaví a věku v době prvních příznaků myastenie. Výsledné skupiny sestávaly ze 152 pacientů.

Výsledky: Mezi spárovanými skupinami nebyl téměř žádný signifikantní rozdíl. Klinická forma, pozitivita protilátek proti acetylcholinovým receptorům, Myasthenia Gravis Composite skóre, doba do stanovení diagnózy, procentuální zastoupení tymomů a tymektomie se významně nelišily. Významný rozdíl byl ale ve zvolené terapii a také v zastoupení oslabení končetin v úvodu onemocnění.

Závěr: Naše výsledky svědčí pro fakt, že alespoň část dříve pozorované heterogenity mezi skupinami pacientů s myastenií může být vysvětlena rozdílným zastoupením mužů a žen a různou věkovou distribucí.

Autoři deklarují, že v souvislosti s předmětem studie nemají žádné komerční zájmy.

Redakční rada potvrzuje, že rukopis práce splnil ICMJE kritéria pro publikace zasílané do biomedicínských časopisů.

Klíčová slova:

myastenie – charakteristiky populace – srovnání – registry

Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a typical autoimmune disorder, since the pathogenic role of auto-reactive antibodies is evident. Detection of muscle-binding antibodies in patients’ sera [1] led to the autoimmune theory of MG in the early 1960s [2]. Further studies described antibodies to several compounds derived from muscle membrane [3] that led to symptoms typical of MG if passively transferred to mice, notably acetylcholine receptor (AChR) and muscle specific kinase (MuSK). [4,5]. Thus, the pathogenesis of MG is clear.

Nevertheless, the triggering factors and the natural course of the disease remain to be elucidated. As the monozygotic twin concordance rate in MG is 35.5% [6], it is certain that genetics plays at least a partial role. Nevertheless, the remaining percentage leaves options open for other factors, such as the environment. According to one systematic review, the incidence and prevalence rates vary greatly depending on where the study took place. The incidence rate ranges from 1.7 to 21.3 cases per mil person-years and the prevalence rate ranges from 15 to 179 per mil [7]. The reason for this marked heterogeneity remains unclear. As different populations have variable access to neurological healthcare, the numbers may by slightly biased by under-diagnosis. However, genetic and environmental factors are very likely to play key roles.

Epidemiological studies revealed still more differences. In European countries, the disease affects mainly adults, while child-onset MG (at under 14 years old) accounts for almost 45% of the MG population in China [8]. Even in European countries, age - and gender-specific incidences are significantly different between populations [7]. Although detailed population-based data on serological subtypes of MG are lacking, the prevalence of MG subtypes does not correlate with overall prevalence. According to unpublished data from Prof. Vincent of Oxford University in the United Kingdom, the reported number of MuSK-MG patients indicates a north-south decline in Europe [9]. Published data on therapy approach and severity expressed by specific outcome measures across different populations are scarce, but the mortality rates (defined as MG-related deaths) range from 0.06 to 0.89 per mil person-years [7].

The aim of this study was to compare the overall management of patients with MG, the severity of the disease, and a number of clinical and laboratory characteristics and therapy approaches in the Czech and Slovak Republics. The Czech and Slovak Republics are neighbouring countries in central Europe that once constituted a single federal republic, known as Czechoslovakia, until 1993. Even though each country has a separate healthcare system now, they share similar systems of compulsory general healthcare insurance, largely accessible to the general population.

Patients and methods

Data were retrospectively collected from two registries in the Czech Republic (Brno, a regional capital city) and the Slovak Republic (Bratislava, the national capital city). The Slovak registry is nationwide (from a state with 5.4 mil inhabitants [10]), and data have been collected since 1977 [11]. The registry in Brno is more local, gathering data from the south-eastern part of the Czech Republic (a region with 1.2 mil inhabitants [12]) since 2001. The following characteristics were retrieved from visits during the January – December 2016 period: age of onset, gender, clinical form, Myasthenia Gravis Composite (MGC) score at the last visit, Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA) classification at the maximum severity of the disease, first symptoms referred to neurologist, time to diagnosis, AChR antibody positivity, history of thymoma, thymectomy, thyreopathy, and modality of treatment at the last visit. The drugs were grouped into cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEI), corticosteroids, azathioprin, ciclosporin, and other immunosuppressants (cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil). The term “early--onset MG” was defined as that occurring at the age under 50 years at first manifestation. All patients who had visited in the period of January – December 2016 were included. The criteria were fulfilled by 189 patients from Brno and 508 from Bratislava.

Patients from each group differed significantly both in age of onset and gender. Therefore, the data were randomly matched by age of onset and gender to enable comparison of all characteristics. The resulting groups consisted of 152 patients each. In consideration of the lack of data normality, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed to compare differences in continuous variables. Fisher’s exact test or Pearson chi-squared test (χ2) was used to compare categorical variables. Statistically significance was set at P < 0.05. Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was used as required. Data analysis was performed using IBM-SPSS software (Version 22, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Statistica (Version 12, StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

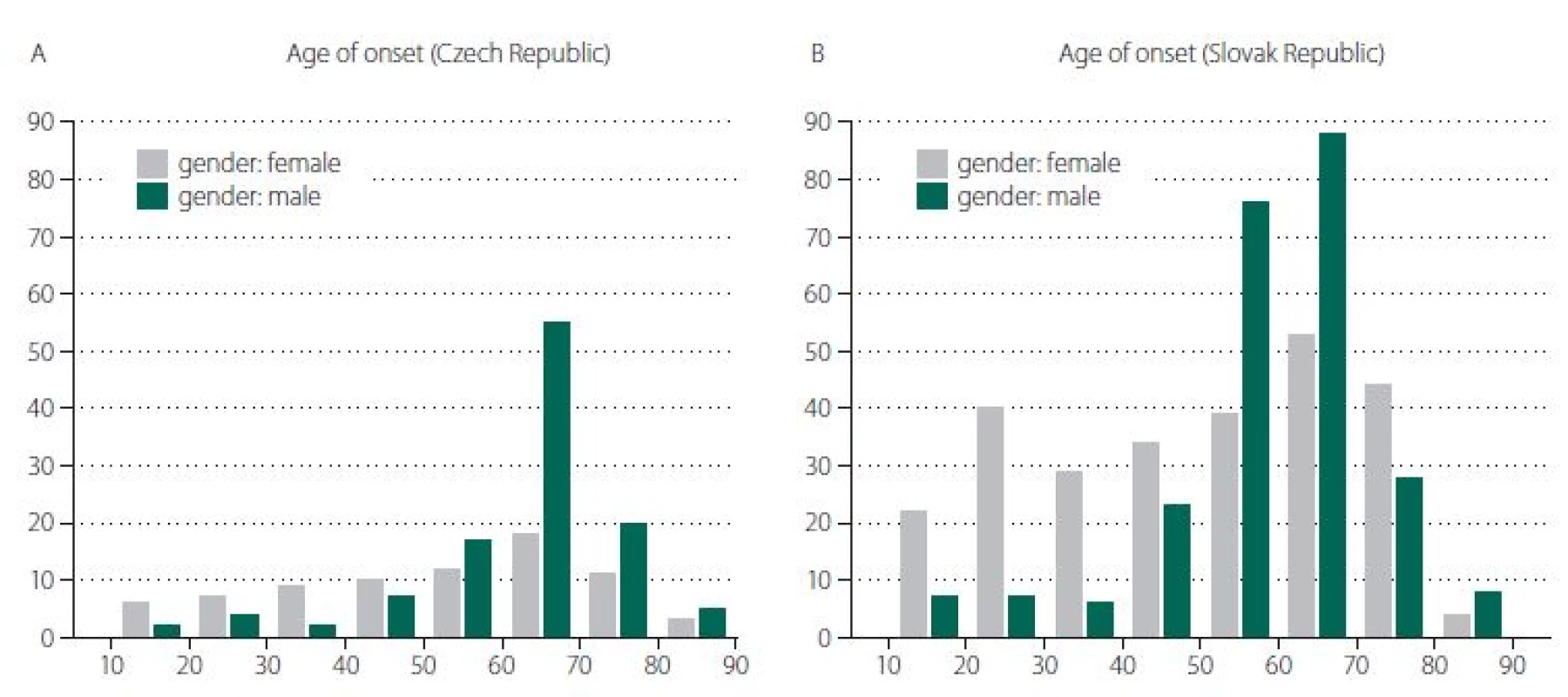

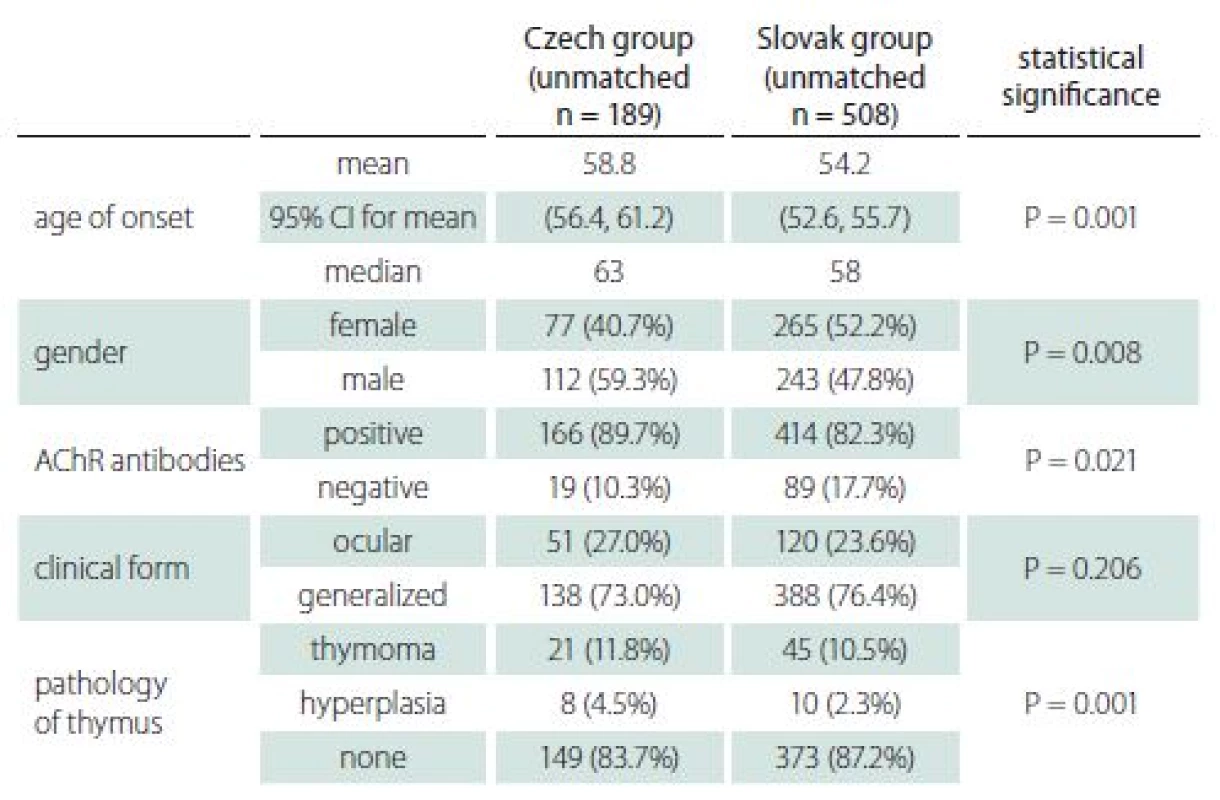

The basic characteristics of the two groups appear in Tab. 1. There was a statistically significant difference between groups in both age of onset (P = 0.001) and gender (P = 0.008), as appears in Fig. 1 A, B. As above, data were then matched by age of onset and gender to enable comparison of all characteristics. Both groups consisted of 152 patients, of whom 44.7% were female. The average age of onset was 57 years in both groups.

Image 1. Distribution of age of onset (in years) in the Czech Republic (A) and the Slovak Republic (B).

Obr. 1. Rozdělení podle věku v době nástupu onemocnění (v letech) v České republice (A) a ve Slovenské republice (B).

Table 1. Basic characteristics of Czech and Slovak groups (unmatched data).

AChR – acetylcholine receptor; CI – confidence interval; n – number Clinical characteristics

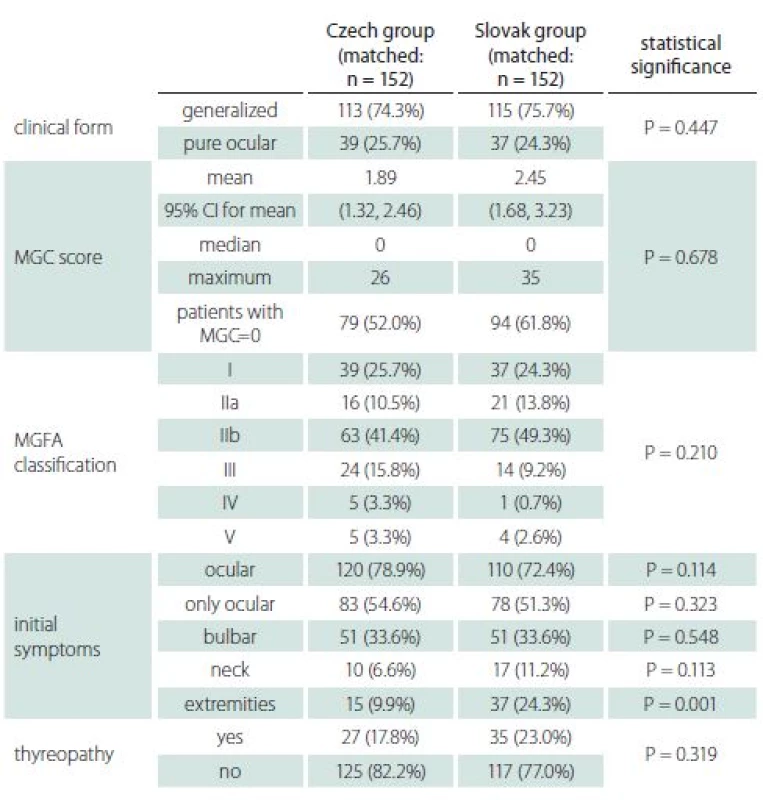

There was almost no significant difference in clinical characteristics between the two groups (Tab. 2), apart from initial occurrence of limb weakness, the proportion of which was higher in the Slovak group. The most common initial symptoms in both groups were diplopia and ptosis (ocular). Furthermore, the ocular symptoms were the only ones present in more than half the patients at the onset of disease; however, only about a quarter of patients sustained with pure ocular form. Half the patients with initially pure ocular symptoms, therefore, developed generalized MG. Even though the average MGC score was higher in the Slovak group, the proportion of patients without symptoms (MGC zero) was also higher in the Slovak group.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics.

CI – confidence interval; MGC – Myasthenia Gravis Composite; MGFA – Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America; n – number Time to diagnosis

In 88.8% of patients from the Czech group and 84.8% of patients from the Slovak group, the diagnosis was made within one year of initial manifestation. The mean and median were similar (Tab. 3) and the difference was not statistically significant.

AChR antibodies

Serology of AChR-antibodies is a routine examination supporting the diagnosis of MG in both countries. Seronegative results appeared in 10.5 and 14.5% of patients in the Czech and Slovak groups respectively, and the difference was not statistically significant. Positivity of AChR-antibodies in both groups increased with age. Whereas 37% of patients in the early-onset group were seronegative, the proportion decreased to 7% in the late-onset group.

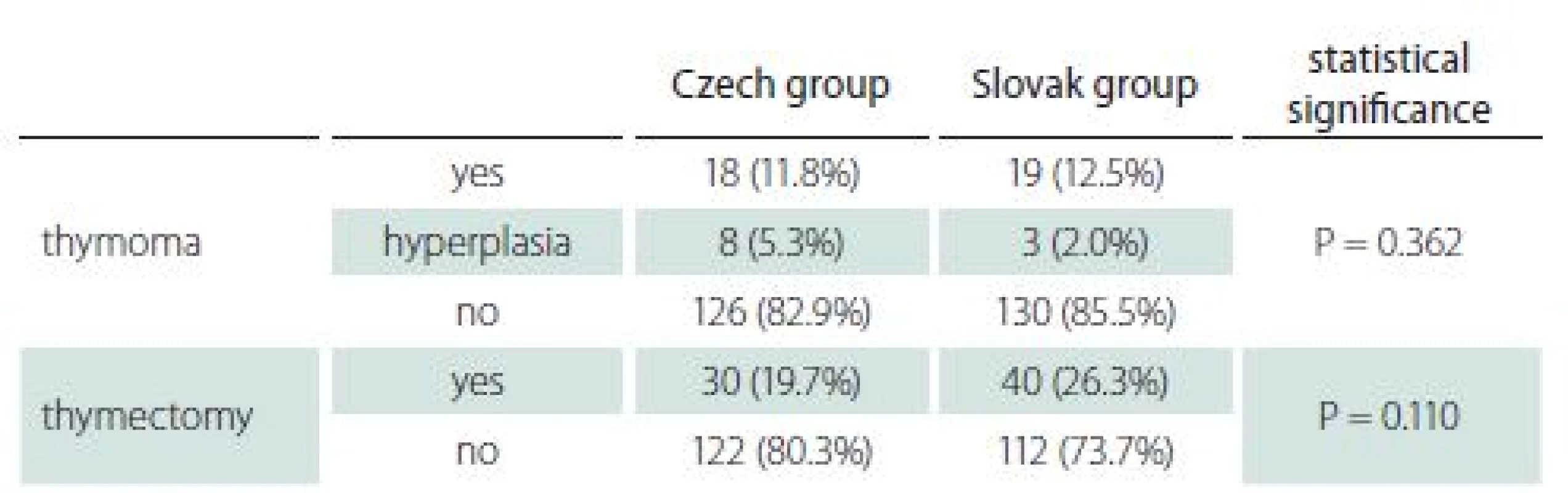

Thymoma and thymectomy

Imaging of the mediastinum represents also a routine procedure in both countries. Thymoma was diagnosed in approximately 12% of patients in both groups (Tab. 4). Occurrence of thymoma did not differ with age in the Slovak group (11.6% in early-onset and 12.8% in late-onset), while in the Czech group thymoma was diagnosed in 27.9 and 5.5% of early - and late-onset MG, respectively.

Table 4. Thymoma and thymectomy.

Therapy

Therapy approaches differed (Tab. 5). Patients in the Czech group received corticosteroids more often compared to ChEI and immunosuppressants.

Table 5. Therapy.

ChEI – cholinesterase inhibitors Discussion

Our data suggest that at least part of the observed heterogeneity between different populations [7] may be based on different gender and age distributions. As the basic characteristics of both unmatched groups reveal in Tab. 1, some differences (particularly in age of onset, gender, and seropositivity of AChR) are obvious. Nevertheless, after correction for differences in age and gender, both groups showed very similar clinical and laboratory characteristics. In particular, MGC score and MGFA classification were not significantly different.

The fact that the MGC score was used uniformly in both groups lends weight to this study. It describes the actual severity of symptoms and thus reflects the patient care and enables more comprehensive comparisons.

As there were only few differences even in matched groups, they should be mentioned. Patients from the Slovak group presented more often with limb weakness among the first symptoms. The reason for this distinction is unclear. As limb weakness in elderly patients might be caused by other comorbidities (spinal and intervertebral disc diseases, polyneuropathy, ischemia, obesity, etc.), such weakness could have been attributed to other causes in the Czech group and not recorded as an MG symptom. Another possible explanation, later diagnosis in the Slovak group with more pronounced symptoms, is not supported by the almost identical time to diagnosis. While there was no difference in the total number of patients with histories of thymoma, there was a clearly higher percentage of thymoma in early-onset myasthenia in the Czech group. This finding is not in agreement with published studies [13,14]. In general, MRI was used as a mediastinal imaging modality in the Czech group, while contrast CT was used in the Slovak group. As the sensitivity of MRI and contrast CT is similar for detecting thymoma, the difference in early-onset thymoma is not explained and the reason for it remains unclear. Nevertheless, the imaging method used might partly explain the higher percentage of hyperplasia in the Czech group, for which MRI is more accurate [15].

Even though there was a clear difference in the choice of treatment modality (Tab. 5), the MGC score in both groups was similar. Therefore, it seems that particular drug choice is probably based on local practice or insurance coverage and does not affect therapeutic response. As more than half the patients were without symptoms at the last visit and the median time to diagnosis was under three months, patient care in both countries appears to be excellent.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, the registry in the Czech Republic is not nationwide, since it covers only a part of the country that is not strictly defined (approximately 1.2 mil of 10.6 mil out inhabitants [12]). Further, as only patients who had visited in the defined period were included, the entire MG population in the Slovak Republic was not covered. This rendered it impossible to calculate and compare prevalence in the two countries. Also, a partial explanation of the observed differences in age and gender may be found in the fact that some patients in a given area were referred to other Czech neuromuscular centres, and diagnosed and treated in them.

Conclusion

We report a comparative study of two MG groups from central Europe. Both groups differed significantly both in age of onset and gender. Nevertheless, the groups were very similar after correction for these factors. The heterogeneity among MG populations is certainly largely due to genetic and environmental factors, but our study suggests that some of this heterogeneity might be explained by different age and gender distributions. This should be taken to account when comparing MG populations.

This publication was written at Masaryk University as a part of the MYO project, ref. MUNI/ A/ 2017, with the support of a Specific University Research Grant, as provided by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic in the year 2017.

Further support was obtained from the Institutional Support of the Ministry of Health, ref. RVO FNBr - 65269705. None of the funding organizations or sponsors was involved in the design and conduct of the study, or the collection, management analysis and interpretation of the data. Tony Long (Svinošice) helped with English style corrections.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

Accepted for review: 12. 12. 2018

Accepted for print: 25. 2. 2019

MUDr. Magda Horáková

Department of Neurology

Faculty of Medicine

Masaryk University

University Hospital

Jihlavská 20 625 00 Brno

Czech Republic

e-mail: magda.horakova@mail.muni.cz

Sources

1. Strauss AJ, Seegal BC, Hsu KC et al. Immunofluorescence demonstration of a muscle binding, complement-fixing serum globulin fraction in myasthenia gravis. Exp Biol Med 1960; 105(1): 184 – 191.

2. Simpson JA. Myasthenia gravis: a new hypothesis. Scott Med J 1960; 5 : 419 – 436.

3. Vrolix K, Fraussen J, Molenaar PC et al. The auto-antigen repertoire in myasthenia gravis. Autoimmunity 2010; 43(5 – 6): 380 – 400. doi: 10.3109/ 08916930903518073.

4. Vincent A, Newsom-Davis J. Acetylcholine receptor antibody as a diagnostic test for myasthenia gravis: results in 153 validated cases and 2967 diagnostic assays. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985; 48(12): 1246 – 1252.

5. Hoch W, McConville J, Helms S et al. Auto-antibodies to the receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK in patients with myasthenia gravis without acetylcholine receptor antibodies. Nat Med 2001; 7(3): 365 – 368. doi: 10.1038/ 85520.

6. Ramanujam R, Pirskanen R, Ramanujam S et al. Utilizing twins concordance rates to infer the predisposition to myasthenia gravis. Twin Res Hum Genet 2011; 14(2): 129 – 136. doi: 10.1375/ twin.14.2.129.

7. Carr AS, Cardwell CR, McCarron PO et al. A systematic review of population based epidemiological studies in myasthenia gravis. BMC Neurol 2010; 10 : 46. doi: 10.1186/ 1471-2377-10-46.

8. Huang X, Liu WB, Men LN et al. Clinical features of myasthenia gravis in southern China: a retrospective review of 2,154 cases over 22 years. Neurol Sci 2013; 34(6): 911 – 917. doi: 10.1007/ s10072-012-1157-z.

9. Koneczny I, Cossins J, Vincent A. The role of muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) and mystery of MuSK myasthenia gravis. J Anat 2014; 224(1): 29 – 35. doi: 10.1111/ joa.12034.

10. Štatistický úrad Slovenskej republiky. Demografia a sociálna štatistika. [online]. Available from URL: https: / / slovak.statistics.sk.

11. Martinka I, Fulova M, Spalekova M et al. Epidemiology of myasthenia gravis in Slovakia in the years 1977 – 2015. Neuroepidemiology 2018; 50.

12. Český statistický úřad. Statistická ročenka Jihomoravského kraje 2015. [online]. Available from URL: https: / / www.czso.cz/ csu/ czso/ statisticka-rocenka-jihomoravskeho-kraje-2015.

13. Berrih-Aknin S, Frenkian-Cuvelier M, Eymard B. Diagnostic and clinical classification of autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J Autoimmun 2014; 48 – 49 : 143 – 148. doi: 10.1016/ j.jaut.2014.01.003.

14. Marx A, Pfister F, Schalke B et al. The different roles of the thymus in the pathogenesis of the various myasthenia gravis subtypes. Autoimmun Rev 2013; 12(9): 875 – 884. doi: 10.1016/ j.autrev.2013.03.007.

15. Pirronti T, Rinaldi P, Batocchi AP et al. Thymic lesions and myasthenia gravis. Diagnosis based on mediastinal imaging and pathological findings. Acta Radiol 2002; 43(4): 380 – 384.Labels

Paediatric neurology Neurosurgery Neurology

Article was published inCzech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

2019 Issue 2-

All articles in this issue

- Intradurálne extramedulárne nádory chrbtice

- Roztroušená skleróza mozkomíšní, úloha střevní mikrobioty v poškozujícím zánětu

- Genetické a neurobiologické aspekty komorbidního výskytu poruch autistického spektra a epilepsie

- Extra-intrakraniální bypass iniciovaný rehabilitačním lékařem pro kognitivní deterioraci

- Traumatické pseudoaneuryzma arterie temporalis superficialis

- Roztroušená skleróza mozkomíšní, těhotenství, mateřství a kojení

- Roztroušená skleróza a těhotenství z pohledu gynekologa – možnosti asistované reprodukce

- Moderní mikrochirurgie jako trvalé, bezpečné a šetrné řešení nekrvácejících mozkových výdutí

- Explantace stimulátoru nervus vagus odpovídající protokolu vyšetření magnetickou rezonancí

- Obecné pohyby a neurologický vývoj raného věku u dětí s novorozeneckou hypoglykemií

- Srovnání kosmetického efektu krátkého podélného a příčného kožního řezu při karotické endarterektomii

- Rychlá diagnostika chemokinu CXCL13 v mozkomíšním moku u pacientů s neuroboreliózou

- Genetika nervosvalových onemocnění

- Analýza dat v neurologii LXXIV. - Neparametrický Spearmanův koeficient korelace

- Recenze knih

- Doc. Vladimír Škorpil, 100 let od narození zakladatele naší elektromyografie

- Hraje leptin roli v rozvoji intrakraniálních meningeomů?

- Srovnávací studie pacientů s myastenií České a Slovenské republiky

- Změny v obsahu esenciálních a stopových prvků v lidských degenerujících meziobratlových ploténkách nekorespondují s klinickým stavem pacientů

- Jak náhrada extracelulárního sodíku ovlivňuje distribuci rychlosti vedení periferním nervem u krysy

- Aneuryzmatické subarachoidální krvácení v těhotenství – úspěšný kliping po selhání koilingu

- Klíšťová meningitida komplikovaná kardioembolickým intraluminálním trombem v krkavici a mozkovou mrtvicí

- Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Intradurálne extramedulárne nádory chrbtice

- Rychlá diagnostika chemokinu CXCL13 v mozkomíšním moku u pacientů s neuroboreliózou

- Genetika nervosvalových onemocnění

- Roztroušená skleróza a těhotenství z pohledu gynekologa – možnosti asistované reprodukce

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career