-

Medical journals

- Career

Surgical options to treat constipation: A brief overview

Authors: J. Pfeifer

Authors‘ workplace: Head and Chair of Department: o. Univ. -Prof. Dr. med. univ. H. J. Mischinger ; Department of Surgery, Medical University of Graz, Austria

Published in: Rozhl. Chir., 2015, roč. 94, č. 9, s. 349-361.

Category: Review

Overview

Patients with intractable chronic constipation should be evaluated with physiological tests after structural disorders and extracolonic causes have been excluded. Conservative treatment options should be tried unstintingly. It should be pointed out that especially new drugs such as prucalopride and linaclotide seem to be a big step forward in treating patients with chronic constipation. If surgery is indicated, for many years subtotal colectomy with IRA was the treatment of choice, although segmental resections were also a good option for isolated megasigmoid, sigmoidocele or recurrent sigmoid volvulus. Nowadays, less invasive procedures like sacral nerve modulation (SNM) should be tried first. If unsuccessful, colectomy can still be considered. In general, patients with a gastrointestinal dysmotility syndrome (GID) should not be offered any surgical options because of their anticipated poor results. Moreover, patients with psychiatric disorders should be actively discouraged from resection, as they tend to have a poorer prognosis. Patients must be counseled that pain and/or bloating will likely persist even if surgery normalizes bowel frequency. Patients with associated problems may be better served by having a stoma without resection as both a therapeutic maneuver and a diagnostic trial. Colectomy is not an option for the treatment of pain and/or abdominal bloating.

In most cases outlet obstruction can be treated successfully with a conservative approach. However, nowadays there are also a variety of surgical options on the market. Each technique has its special place in the armamentarium of a colorectal surgeon but its exact role is not defined yet.

The aim of this article is to give a brief overview, how to diagnose and treat chronic constipation from the standpoint of a colorectal surgeon.

Surgical treatment of chronic constipation is not routine and is performed only in exceptional cases. But one thing first: a “too long gut” (dolichocolon) per se is never an indication for surgery. The aim of this manuscript is to give a brief overview about possible mechanisms of constipation, diagnostic methods and tools and the various conservative and operative treatment options. Moreover, please always keep in mind that constipation may not only be a symptom, but even a distinct disease!Key words:

chronic constipation − surgical treatmentINTRODUCTION

Contrary to popular opinion, chronic constipation is no exclusive “disease of civilization”. Already more than 2500 years ago Egyptians and later Hippocrates in Greece reported on forms of therapy for chronic constipation. With the increase in life expectancy, however, an increase of patients with constipation symptoms can also be seen as digestive problems rise significantly in elderly patients. Epidemiological studies demonstrate that about 15% of the population suffer from chronic constipation in Europe, of which about 2%–3% are children, 8% of the population are middle-aged, but about 30% of the elderly (over 65 years) are affected. The sex ratio women: men is approximately 2 : 1 [1].

Definition

The definition of constipation is sometimes difficult as physicians and patients have different opinions about what constitutes constipation. Patients often present subjective feelings like incomplete evacuation, abdominal or rectal pain, firm stool consistency and need for straining. Currently the most often used definition for chronic constipation is according to the Rome III criteria [2]. A patient complaining about unsatisfactory stools in the last 6 months for at least 3 months and with additionally at least two of the following symptoms:

- Straining during bowel movements in more than 25% of cases

- Feeling of incomplete emptying after a bowel movement in more than 25% of cases

- Hard or pellet-like stools in more than 25% of cases

- Manual maneuvers to facilitate defecation in more than 25% of cases

- Stool frequency <3x per week

Soft and thin bowel movements must not be present, as well as any criteria that would suggest an irritable bowel syndrome. If irritable bowel symptoms are also present, the patient should be classified into the latter group.

Etiology

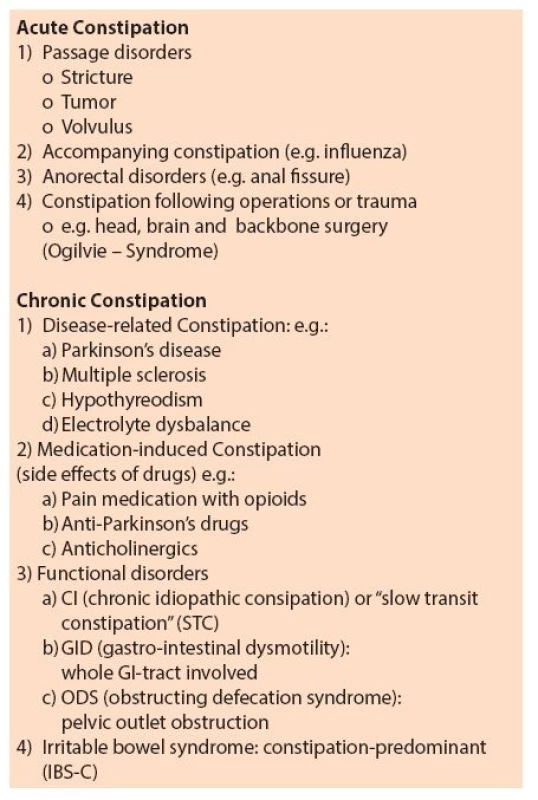

The underlying mechanisms are complex, inconsistent and only partially understood. This often makes it difficult to create a mutually satisfactory classification (Tab. 1). As causal factors for chronic constipation are seldom, primary causes are accepted (e.g. sporadic and familial genetic defects that lead to damaged enteric neurons or myopathy, Hirschsprung disease). More often it is believed that other diseases secondarily lead to disturbances of intestinal transit (e.g. diabetes mellitus, Parkinson’s disease, paraneoplastic syndrome) resulting in degeneration of the intestinal pacemaker cells (Cajal) [3].

1. Classification of constipation by cause

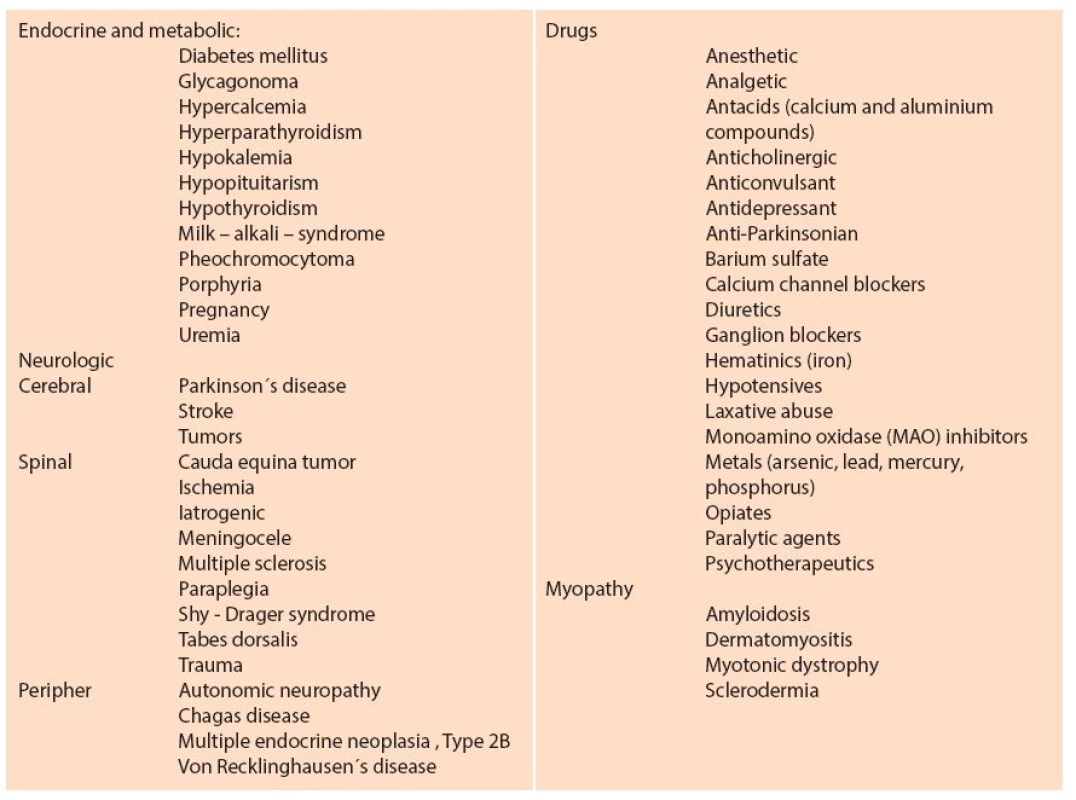

For surgical practice it is important to distinguish between colonic and extra-colonic causes (Tab. 2). Patients who suffer from chronic constipation whose cause does not lie in the colon, never benefit from surgical treatment; nor do patients with symptoms related to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C). However, it can sometimes be difficult to filter out the latter patients. All experts agree that the symptoms of chronic constipation are accompanied by a significant quality of life limitation and higher health costs [4].

2. Extra-colonic causes of constipation

Pathogenesis

Before dealing with the pathogenesis, however, it is necessary briefly to review the normal function of the intestine, including defecation. Thus, the average length of stay of food in the esophagus is about 10 seconds, in the stomach 1–7 hours, depending on the caloric content of food. In the small intestine passage time is 2–4 hours, in the colon more than 24 hours. Overall, the food transit time is about 40 to 60 hours. The normal stool weight is 35–150 g/d and the water content of the stool about 70%. Digestion and absorption happens mostly in the small intestine, electrolyte and water reabsorption in the colon.

Further transport in the digestive tract occurs intermittently by diverse bowel contraction patterns, depending on the filling state and on reflexes. The most famous “gastro-colic reflex” triggers contractions in the colon when the stomach will be filled and thus intestinal content is transported. Another reflex is the “rectoanal-inhibitory-reflex (RAIR)” controlling the opening of the anal canal via an expansion of the rectum; initially partially in the upper portion of the anal canal by relaxation of the internal sphincter. When stool comes in contact with the so-called transition zone “sampling” - that is, the discrimination of hard or liquid stool or gas-occurs. If it is socially appropriate, then there is a full opening of the anal canal through relaxation of the sphincters and defecation is launched with the help of a Valsalva maneuver. If the timing is inconvenient, the arbitrary innervated external sphincter is activated by active squeezing transporting stool content back into the sigmoid colon and thus postponing the urge to defecate.

If you look at the physiological sequence more closely, it becomes clear that there can be many possibilities of failure of passage leading to the development of chronic constipation. For practical reasons, therefore, initially we always want to exclude a morphological substrate (e.g. stricture, colon polyp, tumor).

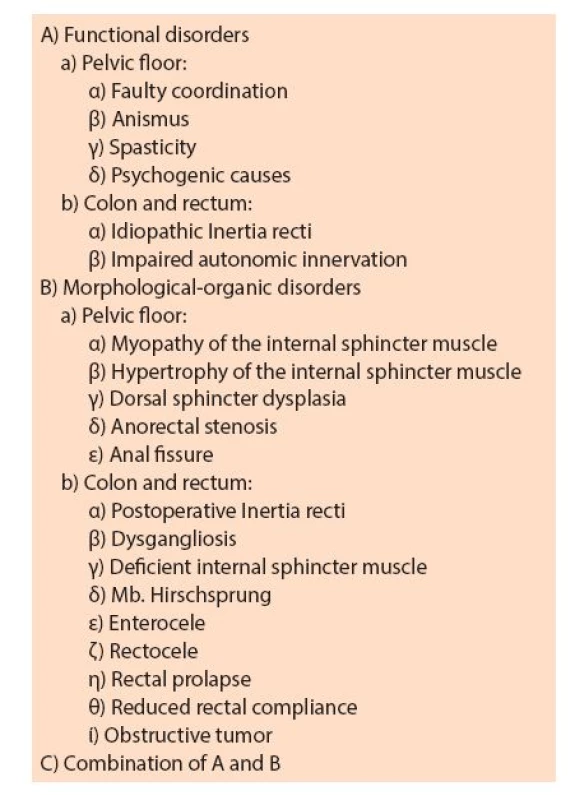

Only when initially no apparent morphological causes are found we speak of a functional disorder. If the subject of fault is only the colon then one speaks of chronic idiopathic constipation (CI, colonic inertia) or “slow transit constipation” (STC); very rarely do patients suffer from a motility disorder of the entire gastrointestinal tract (GID - gastrointestinal dysmotility). The defecation disorder clinically most common located at the pelvic floor is called ODS (“obstructed defecation syndrome”). However, the latter represents a collective term for the most diverse medical conditions (Tab. 3).

3. Syndromes that are summarized under the collective term obstructing defecation syndrome (ODS) (by A. Herold)

Diagnosis

History

In principle, first the following possible warning signs should be sought: bleeding, unexplained weight loss of more than 10%, anemia, malnutrition, paradoxical diarrhoea, age over 50 years, gastrointestinal tumor history (family and personal history), palpable resistance, progressive course, brief history of disease onset. If none of these symptoms are present, conservative, exploratory therapy for 4–8 weeks can be done first.

The management of constipated patients especially requires a detailed history addressing the specifics of bowel activities as well as the ongoing medication profile. Extra-colonic causes of constipation must be systematically excluded before applying terms such as “functional disorder” or “idiopathic constipation”. Questions regarding stool frequency, consistency and tendiousness or completeness of defecation may provide clues as to whether chronic constipation is more likely to be a colon transit or a defecation disorder. However, the symptoms are not unique in this regard, although pressure and flatulence in the upper abdomen rather suggest a STC, while a sense of incomplete emptying after a bowel movement an ODS. Other very important questions are: Duration of constipation (other family members also affected, as a child?) and comorbidities and previous surgery. Several authors report higher rates of constipation in patients after hysterectomy [5].

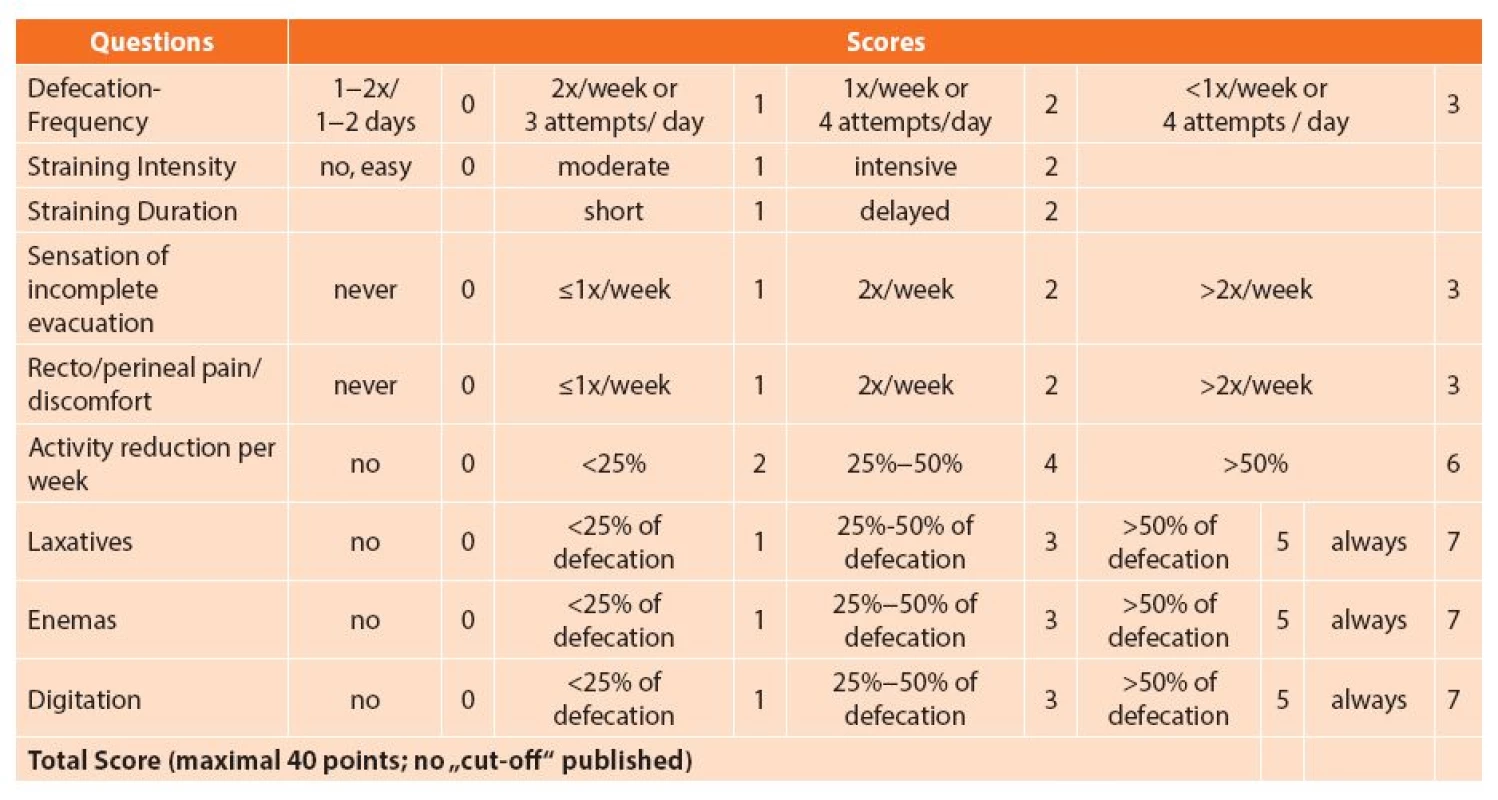

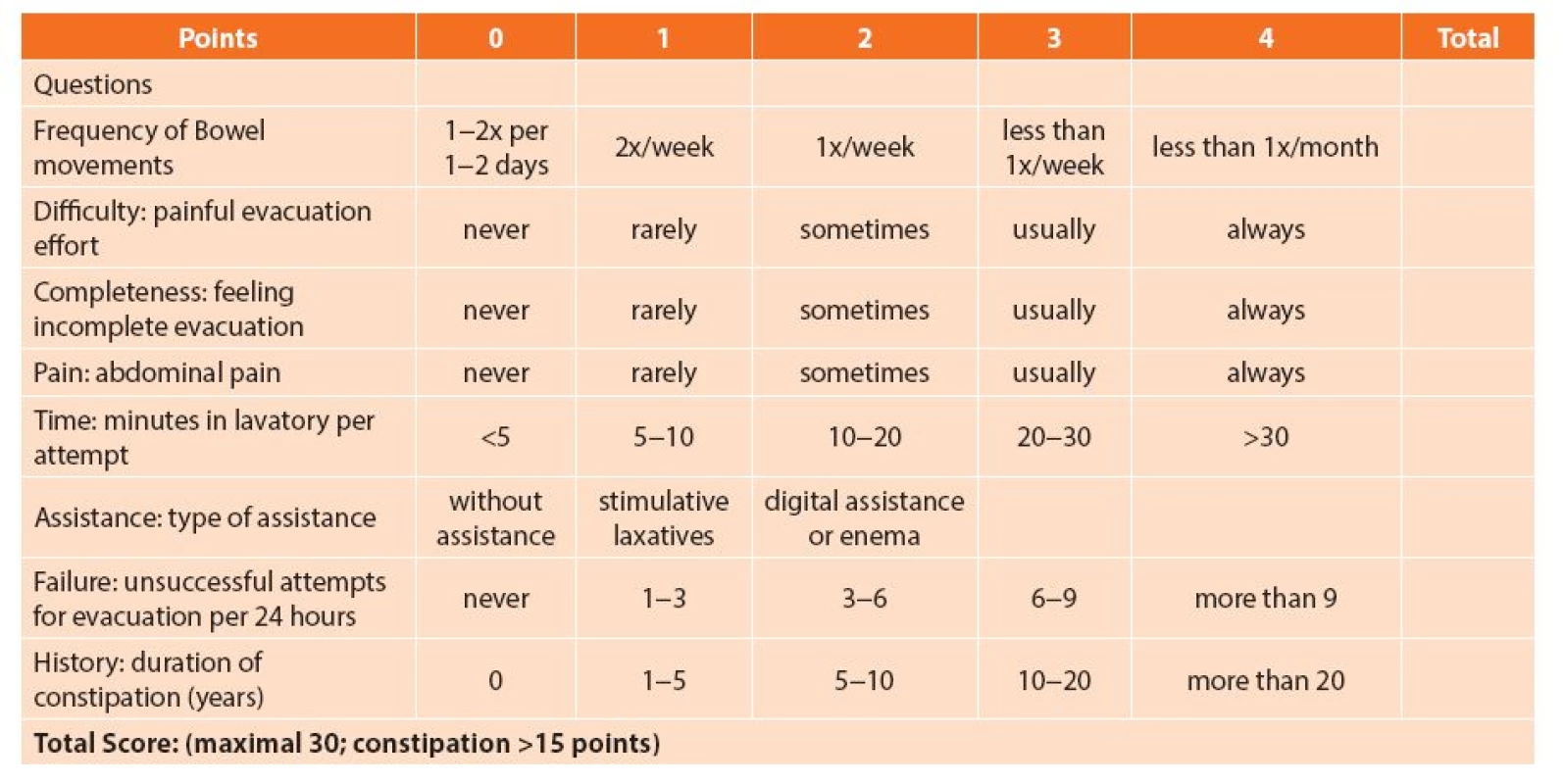

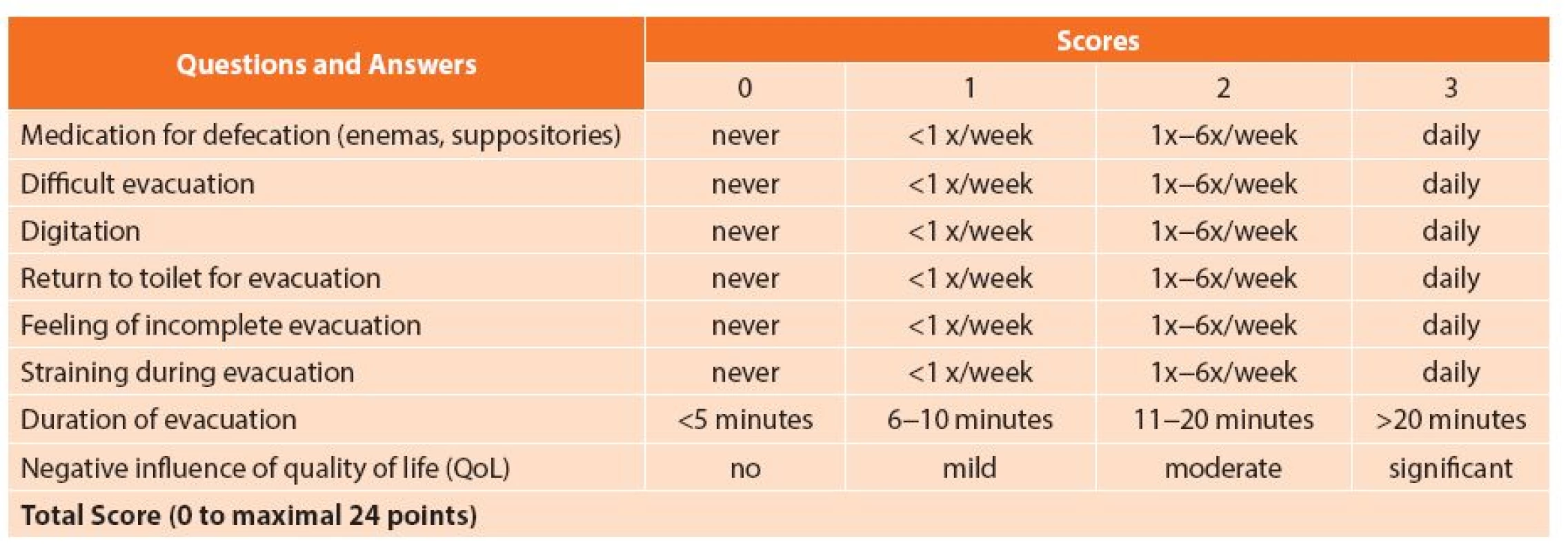

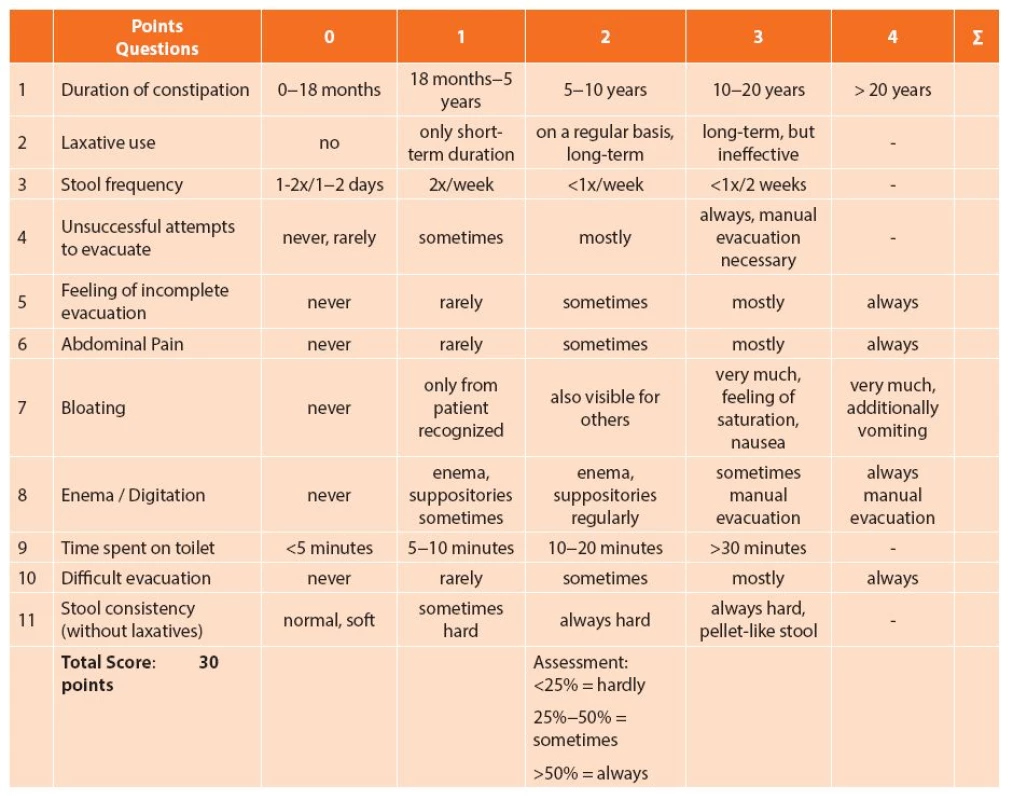

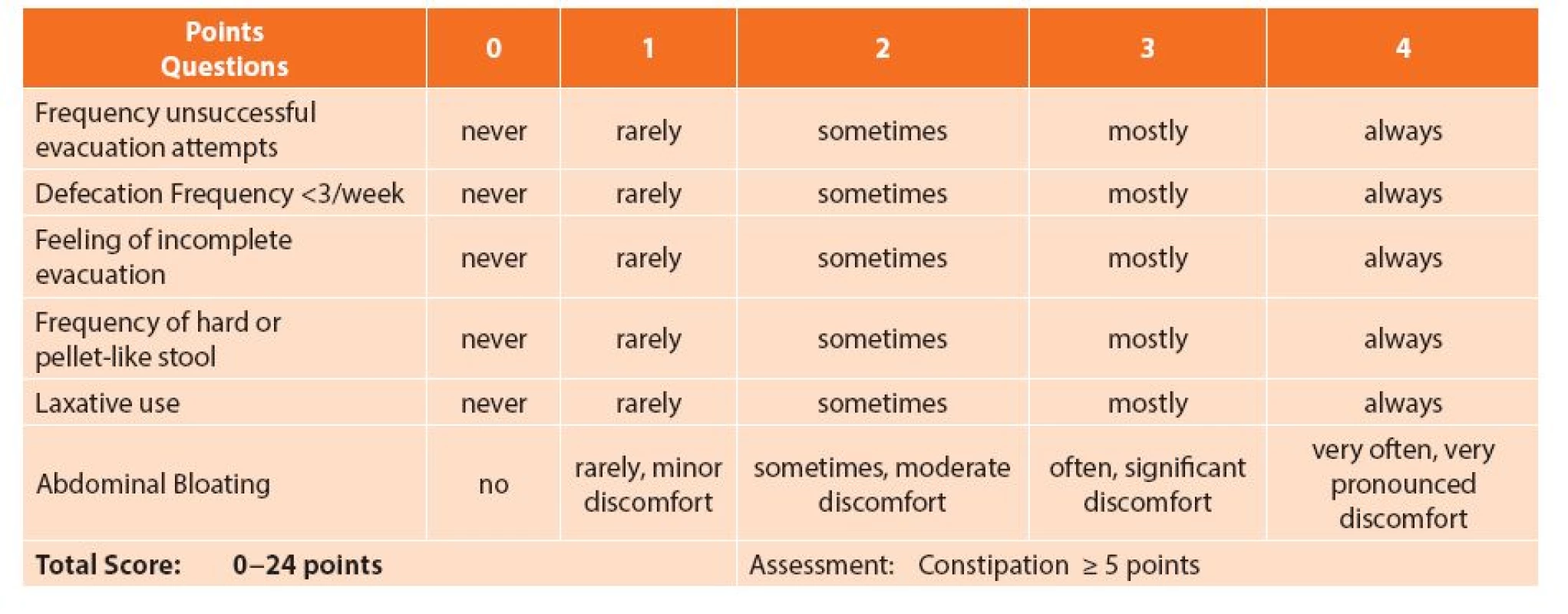

Constipation-Scores

A constipation scoring system helps to classify patients more accurately as candidates for conservative or operative treatment [6]. It is detailed and includes more variables than just stool frequency and consistency. The most frequently used are the Cleveland Clinic Florida Constipation Score (Agachan, Wexner), the ODS score after Longo or its own modified form (MODS), the Knowles - Eccersley-Scott-Symptom Score (KESS) and the Chinese Constipation Questionnaire (CCQ) (Tab. 4–8).

4. Cleveland Clinic Obstipations-Score (Agachan, Wexner)

6. Modified ODS Longo Score (MODS)

7. Knowles-Eccersley-Scott-Symptom Questionaire (KESS)

8. Chinese Constipation Questionaire (CCQ)

Physical examination

The first step involves a complete evaluation of the patient’s present status. Thus a distinction between acute or chronic constipation can be made (Tab. 1). One should pay particular attention to the shape of the abdomen, any scars that exist, bowel sounds and possible pain points. The proctologic examination includes inspection of the anus and the perianal area as well as digital examination. During rectal digitation the patient is asked to squeeze, push down and relax. With this simple test, it is often easy to diagnose pelvic outlet obstruction caused by non-relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles.

Further work up

The next step is proctoscopy without any bowel preparation. Thus, examination of the anal canal and the last 5 cm of the rectum can be assessed. However, if you suspect a possible structural failure of the intestinal transit, colonoscopy should be performed after appropriate bowel preparation, preferably in sedation because of the potential pain.

Blood chemistry, especially serum calcium and potassium levels, as well as thyroxine levels, should be done to rule out hypothyroidism. Only if these tests all fail to reveal a specific diagnosis, then a more exact and time consuming physiological work up is required.

Physiologic tests

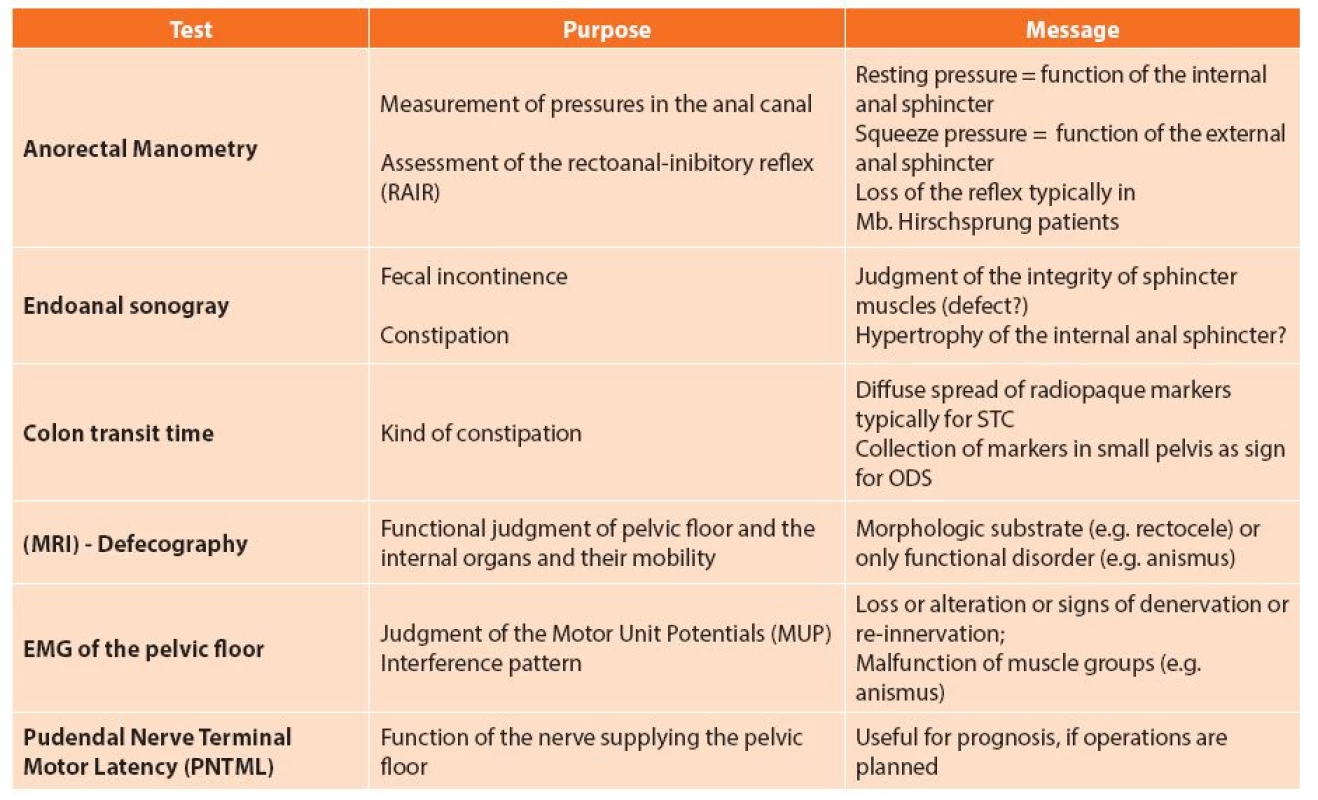

In recent decades our understanding of the causes and development of constipation has improved significantly. If an empirically conservative therapy does not bring desired results, a more detailed evaluation of constipation by means of specific so-called physiologic tests (e.g. colonic transit, anal manometry, defecography) should be performed. It should be noted that a single test often does not provide a clear statement, and therefore the correct diagnosis of constipation can be provided only in conjunction with the clinical presentation and results of several tests. Therefore it is necessary to understand what each individual test may contribute to the diagnosis (Tab. 9).

9. Most often used physiologic tests and their meaningfulness

Interpretation of Results

If no structural cause for constipation is identified, a transit study should be performed. If the transit is normal, evaluation of the pelvic floor should commence. After diagnostic evaluation, constipation can be categorized for surgery as follows:

- 1a) Colonic inertia (CI) or slow transit constipation (STC) with megabowel

- 1b) Colonic inertia (CI) or slow transit constipation (STC) without megabowel

- 1c) Colonic inertia (CI) or slow transit constipation (STC) as part of a comprehensive gut dysmotility syndrome (GID).

- 2a) Obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) with anatomical abnormalities (Hirschsprungs’ disease, perineal descent, rectocele, sigmoidocele, intussusception, rectal prolapse)

- 2b) Obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) without anatomical abnormalities (paradoxical puborectalis contraction, levator spasm, anismus, rectal pain)

- 3. Combined slow transit constipation and obstructed defecation syndrome

- 4. Normal transit constipation (probably due to irritable bowel disease)

Treatment

Indication

In the presence of warning signs or if the patient suffers severely or after failure of conservative therapy, further investigations should be made to exclude a structurally organic cause (such as a colonoscopy, CT scan) or to clarify the pathogenic mechanism of constipation. (e.g. physiological tests).

In principle, , a gradual approach is recommended for the treatment of chronic constipation and surgical treatment options should never come first (Fig. 1).

Conservative Treatment Options

General measures

Among general measures, increased physical activity and enough daily fluid intake (at least 1.5 to 2 liters) is important. Patients should also be advised that especially in the morning after getting up, the motor bowel activity significantly increases physiologically. Therefore, the “gastro-colic reflex” should be utilized by the patients providing plenty of time for a toilet visit (“toilet training”) immediately after breakfast. Furthermore, the function of the reflex can be augmented by administering suppositories that enhance rectal contractility (e.g. glycerin).

A high-fiber diet is an effective way for delayed colonic transit. However, you should be aware that sometimes this diet leads to bloating and cramps.

Laxatives

Different groups of laxatives with different modes of action are now available as drug therapy:

Fillers and bulking agents such as flaxseed, wheat bran, etc. cause water retention in the intestinal lumen. They therefore have their full potency only if simultaneously oral fluid is also increased.

Stimulant laxatives, such as bisacodyl, sodium picosulfate and sennosides are particularly useful for acute constipation disorders. Since they can damage the intestine by excessive, chronic use, these substances are not recommended for long-term use.

Osmotic laxatives that increase the water content of the stool, such as the saline preparations Glauber’s salt or Carlsbad salt have long been part of the repertoire for the treatment of chronic constipation. The problem of saline laxatives, however, is that if they are used in patients with cardiovascular problems or renal dysfunction, fluid and electrolyte shifts by increased absorption of magnesium and sodium may occur. Another osmotic substance is lactulose. However, because lactulose is degraded by intestinal bacteria in the colon, it frequently results in unpleasant bloating for the patient. In addition, there is no linear relationship between the intake of lactulose and amount of stool, which affects the driving ability of this drug.

Newer Medication

Prucalopride (brand name Resolor) is a drug acting as a selective, high affinity 5-HT4 receptor agonist that targets the impaired motility associated with chronic constipation, thus normalizing bowel movements. The substance acts directly on the motor activity of the intestine through stimulation of the peristaltic reflex via serotonergic substances [7].

Other new therapeutic alternatives are secretagogues. These induce water and chloride secretion in the intestinal lumen. This leads to the reduction of stool consistency, increase in stool volume, speeding up of the stool transit time and relief of constipation symptoms. While the substance lubiprostone stimulates only chloride secretion, linaclotide (brand name Constella), a drug from the group of guanylate cyclase C receptor agonists, increases the secretion of chloride and bicarbonate ions in the intestinal lumen through an increase in the intracellular and extracellular concentrations of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) In addition to the increased intestinal fluid secretion and acceleration of gastrointestinal transit, a reduction in visceral hypersensitivity is achieved [8].

Pelvic floor Training (Biofeedback)

Pelvic floor training and re-education programs certainly have a place in the treatment of chronic constipation. Biofeedback training is most successful for ODS showing no morphological substrate. In clinical practice this means that patients with anismus (other names: pelvic floor dysfunction, paradoxical puborectalis contraction) profit most from biofeedback methods [9].

Surgical Treatment Options

Surgery may be considered if conservative treatment options fail [Fig. 2,3]. When looking into the literature it is very difficult to really recognize a precise indication. When talking about patients with chronic constipation you will mostly find a statement such as “Currently there is insufficient evidence to allow any firm conclusions ........“ [10]. Thus choosing a surgical option to treat constipation should never be routine and one shouldn’t be so casual about it.

Fig. 2: Slow transit constipation: treatment algorithm

Fig. 3: Treatment algorithm for pelvic outlet obstruction (obstructed defecation syndrome − ODS)

The next paragraphs give a short description of the most often recommended and suggested operations augmented by a comment followed by an overview about results and possible complications to help the surgeon tailor the right operation to the individual patient.

I. Surgical treatment options for slow transit constipation (CI, STC)

1) Non-resecting surgical treatment options

- A) Malone Antegrade Colonic Enema – MACE

Access: In 1990 Malone first described a surgical technique in which the appendix of the cecum is sewn directly to the skin (appendiceal stoma). Through this approach the large intestine is flushed. If the appendix is not present anymore, a colon conduit can also be formed from the colon wall of the cecum.

Principle of the procedure: The stoma is intubated via a catheter. This way enemas can be administered and thus the entire colon and rectum can be flushed in an orthograde way.

Comment: The great advantage of this method is that possible future necessary operations are not affected. The disadvantage is that especially in adults, high complication rates due to infections have been reported [11].

- B) Sacral Nerve Modulation (SNM) / Sacral Nerve Stimulation (SNS)

Access: The naturally occurring sacral foramina of the sacrum are used for stimulating the nerve plexus using electricity.

Principle of intervention: Continuous direct nerve stimulation can lead to improvement of symptoms not only in patients suffering from anal incontinence but also from constipation (e.g. transit time reduction, increased stool frequency, improvement of rectal sensitivity). Furthermore, a positive modulation of afferent nerve pathways may result.

Surgery is performed in 2 steps: first, test stimulation with a mobile neurostimulator is done. Effectiveness is controlled clinically (e.g. stool diary) whether and how constipation has changed. Only if the test trial is successful (targeted clinical improvement of 50%), a permanent intestinal pacemaker is implanted (often under local anesthesia).

Comment: The best nerve response is usually obtained at the level of S3. In most cases, the test phase to see an effect must be longer in constipated patients compared to incontinent patients (2–3 weeks), before implantation of a permanent pulse generator may be considered[12,13].

2) Resection surgical treatment options

- A) Segmental Resection of the colon

Access: Open or (preferably) laparoscopic resection of the suspected pathological intestinal segment.

Principle of intervention: A targeted resection of the ineffective bowel segment is hoped to normalize the colon transit time.

Comment: The best results of a segmental colon resection are achieved when an isolated megasigmoid (recurrent sigmoid volvulus) is present. An extra long intestine (dolichocolon) or a megacolon/-rectum per se is never an indication for surgery [14].

- B) (Sub-)Total Colectomy

Access: Conventionally, or with a minimally invasive access, the entire colon is resected (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Megacolon in a patient with chronic constipation. Note the thickened muscle wall (taenia coli)

Copyright: M. Stelzer, Medical University of Graz Principle of intervention: Transit time delays in the small intestine are rare. The removal of the entire colon should resolve the problem of delayed transit time.

Comment: The correct indication for surgery is most important! Do not let the patient push you into an operation. This operation does not solve pain or bloating problems nor psychiatric issues. If the indication is right, excellent results (>90% success) can be expected [14,15]. In most cases an ileo-rectal anastomosis (IRA) is performed, even though sometimes it is beneficial to preserve Bauhin’s valve (ceco-rectal anastomosis - CRA). The most common problem after the operation is possible diarrhoea [14–16].

From the surgical perspective, it is surgically more demanding to operate a patient with a megacolon/-rectum compared to a normal subtotal colectomy. Often the anastomosis must be sewn by hand because of the large intestinal lumen cross-section.

II. Surgical treatment options for Obstructed Defecation Syndrome (ODS)

- A) STARR (Stapled Transanal Rectal Resection) (Fig. 5a–g).

Fig. 5A–G: STARR Operation (stapled transanal rectal resection)

With the stapler instrument first the anterior rectal wall is resected in a semicircular way including the excess mucosa (intussusception). After placing another set of sutures the back wall is resected with a second magazine. In this way, the ODS is resolved. Access: This minimally invasive transanal operation method is similar to the so-called stapled hemorrhoidectomy (Longo procedure). The difference is that a full-thickness rectal wall resection is performed.

Principle of the procedure: The indication is an internal rectal prolapse (intussusception) with/without an additional rectocele. This operation aims to resect the obstructing tissue reestablishing normal rectal passage. At the same time the thinned rectal wall is resected (with the additional rectocele). Usually two stapler firings are necessary to resect the anterior and posterior rectal wall separately.

Comment: At the end of the operation, the staple line is about 5–6 cm above the dentate line, which is slightly higher than for a stapled hemorrhoidectomy [17,18].

- B) TRANSTAR (Fig. 6a–e)

Fig. 6 A–E: Stapler-assisted transanal rectal resection with the Contour Transtar device (TRANSTAR)

With this special curved instrument it is possible to resect more mucosa (compared to STARR). The indications are rectal mucosa prolapse as well as internal (intussusception) and external full-thickness rectal prolapse. It is important that the proportion, which should be resected, is mobile and can be pulled outside as far as possible. In most cases 3 -4 magazines are needed. Access: Transanal resection of rectal mucosa and/or wall using a special stapling instrument.

Principle of the procedure: The indication is an internal rectal prolapse (intussusception) with/without additional rectocele, resulting in ODS symptoms, or an overt rectal prolapse.

Comment: The specially designed stapling device is more easily applicable if greater mobility of the rectal mucosa is present. Overall, however, there are always several stapling magazines needed (cost issue).

- C) Internal Delorme (Fig.7a–e)

Fig. 7A–E: Internal Delorme

After injecting of 1% xylocaine/epinephrine solution under the distal rectal mucosa to separate the anatomical layers and to reduce bleeding, a circular mucosa ring is resected. Then a longitudinal plication of the rectal muscle with 4 stitches (in each quadrant) is done, followed by a manual mucosa-mucosa anastomosis with interrupted sutures. Access: Transanal resection of the rectal mucosa within the lumen of the rectum.

Principle of the procedure: The procedure is indicated for internal rectal prolapse (intussusception) with/without an additional rectocele, leading to ODS symptoms. After the circular mucosal resection, plication stitches of the muscular wall followed by a mucosa-mucosa anastomosis are performed.

Comment: Injection of adrenaline solution (in all 4 quadrants) of the submucosa causes a lifting of the mucosa, minimizes intraoperative bleeding and ensures a good overview during resection.

- D) Rectocele Resection (Fig. 8a–e)

Fig. 8A–E: Transvaginal rectocele resection

Transverse incision at the introitus vaginae after injection of 1% xylocaine/epinephrine solution to reduce bleeding and to separate the anatomical layers. Next the preparation of the large rectocele is done followed by its resection with an Endo-GIA instrument. Usually 2–3 magazines are necessary. A staples-covering running suture is advisable. An adaptation of the pelvic floor muscles (levatorplasty) can be added but keep in mind that a higher incidence of dyspareunia is expected. Finally, the wound is closed again. Access: In principle, the approach to resect a rectocele can be done through the anus, vagina or transperineally (with/without levatorplasty)

Principle of the procedure: Very large rectoceles may best be resected transvaginally.

Comment: After a transverse incision at the introitus of the vagina, dissection of the thinned wall of the rectocele by use of an endostapling device is done. Usually 2–3 magazines are needed. The staple line is covered with a running suture before closing the incision. Levatorplasty should be done only in elderly women due to the risk of dyspareunia postoperatively. In such a situation gynecologists usually perform a posterior transvaginal rectocele repair without resection (posterior colporrhaphy).

- E) Laparoscopic “ventral” rectopexy

Access: Up to 5 trocars are needed for this operation, with the camera port located at the navel.

Principle of intervention: The indications for this procedure are rectoceles, sigmoidoceles with/without intussuception or a rectal prolapse. After mobilizing the rectum up to the pelvic floor, it is fixed to the sacrum with the help of a mesh and sutures. Sometimes additional resection of the sigmoid colon might be necessary.

Comment: Mobilization of the rectum should be done only from anterior and posterior; the lateral stalks should be left intact. If a bowel resection is done, fixation of the rectum should be done without a mesh [21,22].

III. Surgical treatment options for a combined slow transit constipation and obstructed defecation syndrome

Usually outlet obstruction is treated first (with conservative methods e.g. biofeedback). If this is not successful, one should be very careful before operating the patient [14]. The patient’s expectations are often beyond the possibilities of surgery. However, minor surgeries might improve the patient’s quality of life (see below).

- A) Sacral Nerve Modulation (SNM) / Sacral Nerve

Stimulation (SNS)

For principles and technique see above (paragraph I 1 B).

- B) Stoma (Fig. 9)

Fig. 9: Stoma

Copyright: M. Stelzer, Medical University of Graz Access: The stoma can be done laparoscopically or conventionally.

Principle of the procedure: The advantage is that the operation is reversible and can be used as an invasive test before a (final) resection.

Comment: If you suspect a gastrointestinal dysmotility disorder, an ileostomy should be created, otherwise a colostomy. If the complaints of the patient despite ileostomy do not improve, then the GID is confirmed; if improved then the fault is located in the colon or we are dealing with a combination of STC and ODS. If ODS is the primary cause, a colostomy will improve constipation.

Results and Complications

Intraoperative

The most important issue for functional operations is the right indication. It is very important to give the patient a realistic expectation. Pain, meteorism cannot be improved with an operation; only the transit time can be shortened. Accurate diagnosis and evaluation of quality of life are prerequisites for a successful operation and a satisfied patient. Only in cases of failure of conservative measures may surgery be considered. For example, if the colonic transit study results in a diffuse marker distribution, this study should be repeated before an operation is done. Otherwise a failure rate of approximately 30% can be expected [23].

For planned segmental resections additional scintigraphic transit time studies (nuclear scans) should be carried out [24].

Often patients suffering with chronic constipation have additional psychiatric disorders [14,16]. Therefore, physiological investigation and a psychiatric assessment preoperatively are essential to carry out a coordinated and patient specific therapy. In principle, outlet obstruction is significantly more likely than slow transit constipation.

In abdominal surgery all common complications are possible (e.g. anastomotic leak, injury of the ureter, peritonitis, etc.).

In proctologic operations bleeding is the most often seen complication. Injection with 1% xylocaine/epinephrine solution often reduces bleeding and helps to better identify the anatomical layers of the intestinal wall (e.g. Internal Delorme - operation). After stapling procedures, targeted stitches on the staple line are often required [25].

Postoperative

Short-term complications include bleeding and sometimes stool regulation problems (stools which are either too liquid or too firm). The adaptive processes for regular function of the defecation process often require several months; the same applies to an undisturbed sexual function (in patients where still important).

Long-term complications

The complication rate of Malone surgery (MACE) in adults varies between 33% and 67%. Among the most common are particularly local stoma problems (stenosis, retraction), wound infections or psychological problems [11].

Segmental colon resections achieve worse results (about 60%–75%) in comparison with total colectomy (about 70%–100%) [14,16]. Nevertheless, these operations should only constitute an exceptional case as the last therapeutic option. The most common long-term complications are obstruction due to small bowel adhesions. In up to 15% of patients hospitalization and in up to about 10% re-operations are required. This has not significantly improved even by minimally invasive surgical techniques [14,26].

Surgery for ODS usually improves quality of life as measured with a scoring system. However, quite often additional drugs and suppositories and enemas are needed. A dreaded complication of a stapling operation is the pathological urge to defecate (“urgency”), which can occur in up to 13% of cases [25]. Restraint in making judgements for an operation should be taken in sexually active women, as proctologic operations can unpredictably result in dyspareunia.

CONCLUSION

In selected cases surgical treatment for patients with chronic constipation can be successful. However, knowledge of the various surgical techniques and their advantages and disadvantages is a prerequisite to tailor the best procedure for the individual patient.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have not conflict of interest in connection with the emergence of and that the article was not published in any other journal.

Johann Pfeifer, MD

Department of General Surgery University Surgical Clinic

Medical University of Graz

Auenbruggerplatz 29

8036 Graz, Austria

e-mail: johann.pfeifer@medunigraz.at

Sources

1. Andresen V, Enck P, Frieling T, et al. S2k-Leitlinie Chronische Obstipation: Definition, Pathophysiologie, Diagnostik und Therapie. AWMF-Registriernummer: 021/019 – S2k-Leitlinie Chronische Obstipation aktueller Stand: 02/2013.

2. Shih DQ, Kwan LY. All Roads Lead to Rome: Update on Rome III Criteria and New Treatment Options. Gastroenterol Rep 2007;1 : 56–65.

3. Huizinga JD, Chen JH. Interstitial cells of Cajal: update on basic and clinical science. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2014;16 : 363.

4. Basilisco G, Coletta M. Chronic constipation: a critical review. Dig Liver Dis 2013;45 : 886–93. Epub 2013 Apr 30.

5. Martinelli E, Altomare DF, Rinaldi M, et al. Constipation after hysterectomy: fact or fiction? Eur J Surg 2000;166 : 356–68

6. Agachan F, Chen T, Pfeifer J, et al. A constipation scoring system to simplify evaluation and management of constipated patients. Dis Colon Rectum 1996;39 : 681–5.

7. Keating GM. Prucalopride: a review of its use in the management of chronic constipation. Drugs 2013;73 : 1935–50.

8. Jarmuż A, Zielińska M, Storr M, et al. Emerging treatments in Neuro-gastroenterology: Perspectives of guanylyl cyclase C agonists use in functional gastrointestinal disorders and inflammatory bowel diseases. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015; Apr 30. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12574.

9. Woodward S, Norton C, Chiarelli P. Biofeedback for treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; Mar 26;3:CD008486. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008486.pub2

10. Arebi N, Kalli T, Howson W, et al. Systematic review of abdominal surgery for chronic idiopathic constipation. Colorectal Dis 2011;13 : 1335–43.

11. Meurette G, Lehur PA, Coron E, et al. Long-term results of Malone’s procedure with antegrade irrigation for severe chronic constipation. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2010;34 : 209–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2009.12.009. Epub 2010 Mar

12. Kamm MA, Dudding TC, Melenhorst J, et al. Sacral nerve stimulation for intractable constipation. Gut 2010;59 : 333–40.

13. Carrington EV, Evers J, Grossi U, et al. A systematic review of sacral nerve stimulation mechanisms in the treatment of fecal incontinence and constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26 : 1222–37.

14. Pfeifer J, Agachan F, Wexner SD. Surgery for constipation: a review. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39 : 444–60.

15. Reshef A, Alves-Ferreira P, Zutshi M, et al. Colectomy for slow transit constipation: effective for patients with coexistent obstructed defecation. Int J Colorectal Dis 2013;28 : 841–7.

16. Pfeifer J. Surgery for constipation. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2006;53 : 71–9

17. Ribaric G, D’Hoore A, Schiffhorst G, et al and TRANSTAR Registry Study Group. STARR with CONTOUR® TRANSTAR™ device for obstructed defecation syndrome: one-year real-world outcomes of the European TRANSTAR registry. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014;29 : 611–22.

18. Zhang B1, Ding JH, Zhao YJ, et al. Midterm outcome of stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation syndrome: a single-institution experience in China. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19 : 6472–8.

19. Ganio E, Martina S, Novelli E, et al. Internal Delorme’s procedure for rectal outlet obstruction. Colorectal Dis 2013;15:e144–50.

20. Podzemny V, Pescatori LC, Pescatori M. Management of obstructed defecation. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21 : 1053–60.

21. Laubert T1, Kleemann M, Roblick UJ, et al. Obstructive defecation syndrome: 19 years of experience with laparoscopic resection rectopexy. Tech Coloproctol 2013;17 : 307–14.

22. Mercer-Jones MA1, D’Hoore A, Dixon AR, et al. Consensus on ventral rectopexy: report of a panel of experts. Colorectal Dis 2014;16 : 82–8.

23. Hedrick TL, Friel CM. Constipation and pelvic outlet obstruction. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2013;42 : 863–76.

24. Yik YI, Cain TM, Tudball CF, et al. Nuclear transit studies of patients with intractable chronic constipation reveal a subgroup with rapid proximal colonic transit. J Pediatr Surg 2011;46 : 1406–11.

25. Naldini G1, Martellucci J, Rea R, et al. Tailored prolapse surgery for the treatment of haemorrhoids and obstructed defecation syndrome with a new dedicated device: TST STARR Plus. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014;29 : 623–9. Epub 2014 Feb 26.

26. Alvarez-Downing M1, Klaassen Z, Orringer R, et al. Incidence of small bowel obstruction after laparoscopic and open colon resection. Am J Surg 2011;201 : 411–5;discussion 415.

Labels

Surgery Orthopaedics Trauma surgery

Article was published inPerspectives in Surgery

2015 Issue 9-

All articles in this issue

- Gastric stump cancer – unicentric analysis of 7 patients

- Cholecystostomy – an obsolete or relevant treatment?

- The use of hybrid revascularization procedures for the therapy of multilevel lower extremity arterial disease – analysis of single center experience

- Choledochal cyst

- Extraintestinal GIST – case report

- Surgical options to treat constipation: A brief overview

- Perspectives in Surgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Surgical options to treat constipation: A brief overview

- Cholecystostomy – an obsolete or relevant treatment?

- Choledochal cyst

- Extraintestinal GIST – case report

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career