-

Medical journals

- Career

Neurosurgical resident training in the Czech Republic

Authors: D. Netuka 1; M. N. Stienen 2; F. Ringel 3; J. Gempt 4; A. K. Demetriades 5; K. Schaller

Authors‘ workplace: Neurochirurgická a neuroonkologická klinika 1. LF UK a ÚVN - VFN Praha 1; Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland 2; Department of Neurosurgery, Universitätsmedizin der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany 3; Department of Neurosurgery, Klinikum Rechts der Isar, Technical University Munich, Germany 4; Department of Neurosurgery, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, United Kingdom 5; Department of Neurosurgery and Faculté de Médicine, University Hospital of Geneva, Switzerland 6

Published in: Cesk Slov Neurol N 2018; 81(1): 66-72

Category: Original Paper

doi: https://doi.org/10.14735/amcsnn201866Overview

Introduction:

Resident training is essential to be able to offer high-quality medical care. Neurosurgical training in its traditional form is currently challenged by law-enforced working hour restrictions and general re-structuring within Europe. We aimed to evaluate the current situation of resident training in the Czech Republic.Methods:

An electronic survey was sent to European neurosurgical trainees between 06/ 2014 and 03/ 2015. The responses of Czech trainees were compared to those of trainees from other European countries. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the effect size of the relationship between a trainee from the Czech Republic and the outcomes (e. g. satisfaction, working time).Results:

Of n = 532 responses, 22 were from Czech trainees (4.14%). In a multivariate analysis, Czech trainees were as likely as non-Czech European trainees to be satisfied with clinical lectures given at their teaching facility (OR 1.84; 95% CI 0.77 – 4.43; p = 0.170). The satisfaction rate with hands-on operating room exposure was nonsignificantly higher than in other European countries (OR 3.22; 0.72 – 14.39; p = 0.125). Approximately 100% of Czech trainees vs. 88.7% of trainees from other European countries performed a surgical procedure as the primary surgeon within the first year of training (Pearson Chi2 test 2.28; p = 0.131). They were about 4-times as likely to begin with their own cranial cases within 36 months of training (OR 3.69; 1.04 – 13.07; p = 0.042). Czech trainees were 52-times as likely to perform on average ≥ 4 peripheral nerve interventions per month (OR 52.05; 11.46 – 236.31; p < 0.001), but less likely to operate ≥ 10 burr hole trepanations (OR 0.13; 0.02 – 0.97; p = 0.047) and the exposure was balanced regarding craniotomies and spine procedures. About 72% of Czech trainees adhered to the weekly limit of 48 h as requested from the European Working Time Directive 2003/ 88/ EC, and this was better than the international comparison (OR 0.26; 0.09 – 0.75; p = 0.013).Conclusion:

Most theoretical and practical aspects of neurosurgical training are rated similarly by Czech trainees when compared to the situation of trainees from other European countries. They adhered better to the 48 h week as requested by the European WTD 2003/ 88/ EC.Key words:

resident education – surgical education – neurosurgery – European Working Time Directive – future perspective – training conditions – satisfaction rate – craniotomy – spine surgery – working time – Czech Republic

Chinese summary - 摘要

捷克共和国的神经外科住院医师培训

介绍:

住院培训对提供高质量的医疗护理至关重要。传统形式的神经外科培训目前受到欧洲法律规定的工时限制和一般重组的限制。 我们旨在评估捷克共和国住院培训的现状。

方法:

电子调查表于2014年6月至2015年3月期间发送给欧洲神经外科学员。捷克学员的答复与其他欧洲国家的学员进行了比较。 使用Logistic回归分析来评估捷克共和国的受训者与结果(例如满意度,工作时间)之间影响效应的大小。

结果:

在532份的回复中,22份来自捷克学员(4.14%)。在多变量分析中,捷克受训者与非捷克欧洲受训者一样对他们的教学单位给予的临床讲座感到满意(OR 1.84; 95%CI 0.77-4.43; p = 0.170)。临床动手实践的满意率无显著高于其他欧洲国家(OR 3.22; 0.72-14.39; p = 0.125)。在培训的第一年内,大约100%的捷克受训者与88.7%的来自其他欧洲国家的受训者作为主刀外科医生进行了外科手术(Pearson Chi2 test 2.28; p = 0.131)。他们在36个月内大约执行4次颅骨手术(OR 3.69; 1.04-13.07; P = 0.042)。捷克受训者一年52次,平均每月进行≥4次周围神经干预(OR 52.05; 11.46-236.31; p <0.001),但平均每月≥10次钻孔的可能性较低(OR 0.13; 0.02-0.97; p = 0.047),在开颅手术和脊柱手术的暴露中均衡。根据欧洲工作时间指令2003/88 / EC的要求,约72%的捷克学员坚持每周48小时制度,这比国际标准较好(OR 0.26; 0.09-0.75; P = 0.013)。

结论:

捷克受训者对神经外科训练的大多数理论和实践的评价与来自其他欧洲国家的受训者的评价类似。 根据欧洲WTD 2003/88 / EC的要求,他们坚持48小时更好。

关键词:

住院教育 - 外科教育 - 神经外科 - 欧洲工作时间指令 - 未来视角 - 培训条件 - 满意率 - 开颅手术 - 脊椎手术 - 工作时间 - 捷克共和国Introduction

Resident training is one of the most important aspects of the daily clinical work in an academic teaching hospital. In neurosurgery, a great amount of theoretical and practical training is required in order to become familiar with a broad variety of pathologies and treatments. Traditionally, these skills have been acquired during the difficult years of residency, where trainees literally lived in hospitals, eagerly serving and watching their superiors operate while becoming increasingly independent. Nowadays, surgical training has lost much of its archaic character, and while law-enforced working time limits have come into play, the education of trainees is automatically reduced. Modern training concepts try and offset some of these deficits by the progressive use of training courses, hand-on workshops and standards in training, e. g. by the European Association of Neurosurgical Societies (EANS) [1 – 4]. It was in the light of the political developments of the past few years that a survey was started amongst European neurosurgical trainees. This survey aimed to determine working time, training conditions and satisfaction rates in different EANS member states. While the results have recently been published, the present work aimed at specifically analysing the responses of neurosurgical trainees from the Czech Republic (CR) and comparing them to the situation in other European countries [5,6].

Methods

The method of data collection has been described in more detail before [5]. In short,an online survey consisting of 33 questions was distributed amongst European neurosurgical trainees between 06/ 2014 and 03/ 2015. Trainees were invited to attend the EANS training course in Nicosia, Cyprus (August 2014) and Uppsala, Sweden (February 2015), by direct e-mail contact and by using social media platforms (Facebook, etc.). Participants were ensured about confidentiality of their data. All data were collected in an online database and subsequently exported into Excel. Questionnaires of all responders obtained until 30/ 04/ 2015 were included in the final analysis.

Statistical considerations

Frequency distributions and summary statistics were calculated for all questions with categorical answers. Parameters such as satisfaction rates, timing of surgical procedures or caseloads were additionally turned into a binary variable (e. g. satisfied vs. non-satisfied, < 12 months vs. ≥ 12 months, < 10 vs. ≥ 10 procedures/ month). Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the size effect of the relationship between a trainee being from the CR and the outcomes (e. g. satisfaction, working time). First, a univariate model was built to assess the relationships without adjustment, and then a multivariate model was built using forced-entry methodology. Multivariate analysis was corrected for age, gender, postgraduate year (PGY) and type of clinic as those were imbalanced at baseline and/ or considered to be potential confounders. Results of the multivariate analysis are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The software used for the statistical analysis was Stata v14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). Graphs were drawn using GraphPad Prism v5.0c (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, California, USA).

Results

A total of 652 responses were collected. One hundred and twenty responses were excluded because: a) the responders stated that they were not neurosurgical residents (n = 87); or b) the responders indicated to be working in a non-European country (n = 33). Thus, 532 responses were taken into consideration, of which 22 (4.14%) were from Czech trainees. Most of the non-Czech responders worked in Germany, in the United Kingdom (UK), Switzerland, Italy, Poland, Ukraine, Portugal, Netherlands, Greece, Spain and Turkey. Fourteen residents (3%) indicated working in Europe, but did not specify their country [7].

Table 1 shows the baseline parameters of the study cohorts. The age - and sex-distribution of Czech and non-Czech trainees was similar and trainees from the CR, much likly than in the rest of Europe, mostly worked at university departments. Czech units were smaller concerning the number of trainees, but had a similar or even higher case load for cranial and spinal cases/ year respectively.

Theoretical education

In the multivariate analysis, Czech trainees were 184% as likely as non-Czech European trainees to be satisfied with clinical lectures given at their teaching facility (OR 1.84; 95% CI 0.77 – 4.43; p = 0.170). They were 100% as likely to be satisfied with anatomical lectures (1.00; 0.36 – 2.76; p = 0.994), 77% as likely to be satisfied with journal clubs (0.77; 0.29 – 2.05; p = 0.609), 118% as likely to be satisfied with teaching during ward rounds (1.18; 0.41 – 3.43; p = 0.756), 198% as likely to be satisfied with tumour boards (1.98; 0.63 – 6.28; p = 0.243) and 156% as likely to be satisfied with teaching during radiology boards (1.56; 0.54 – 4.54; p = 0.406).

Practical education

In the multivariate analysis, Czech trainees were 322% as likely as non-Czech European trainees to be satisfied with hands-on operative training at their teaching facility (3.22; 0.72 – 14.39; p = 0.125). They were 188% as likely to be satisfied with microsurgical training (1.88; 0.69 – 5.16; p = 0.219), 174% as likely to be satisfied with simulator training (1.74; 0.54 – 5.54; p = 0.351), 72% as likely to be satisfied with cadaver training (0.72; 0.20 – 2.59; p = 0.625), and 157% as likely to be satisfied with decision-making (1.57; 0.35 – 7.10; p = 0.552).

Timing of surgery

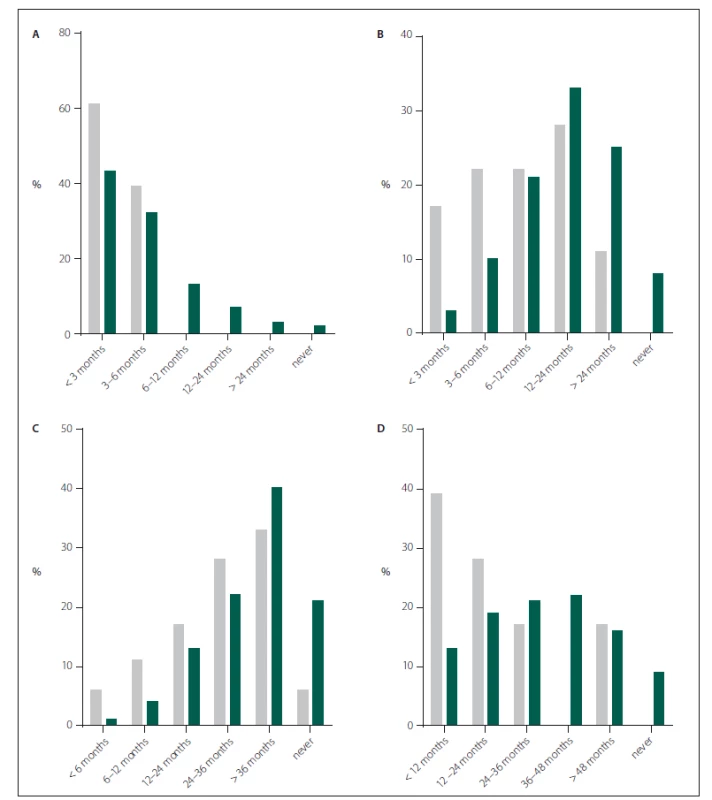

The timing concerning several types of neurosurgical procedures performed by Czech residents is displayed in Fig. 1. In general, 100% of Czech and 88.7% of non-Czech European residents indicated that their first surgical procedure as primary a surgeon was carried out within the 1st year of training (Pearson Chi2 test 2.28; p = 0.131). Czech trainees were 83% as likely to begin with their own lumbar spine surgery at < 12 months (OR 0.83; 0.25 – 2.70; p = 0.756), 216% as likely to begin with their own cervical spine surgery at < 24 months (OR 2.16; 0.77 – 6.03; p = 0.142), and 369% as likely to begin with their own cranial cases at < 36 months of training (OR 3.69; 1.04 – 13.07; p = 0.042).

1. Histograms depicting the timing of surgeries as primary surgeons for various neurosurgical procedures at their training facility as indicated by 22 Czech (grey bar) and 510 non-Czech (green bar) European neurosurgical trainees. Fig. 1A) Any surgical procedure (including relatively simple procedures such as burr holes for ventriculostomy, chronic subdural hematomas, intracranial pressure probes). Fig. 1B) Lumbar spine surgery. Fig. 1C) Cervical spine surgery. Fig. 1D) Craniotomy (e.g. for traumatic brain injury or tumour surgery).

Caseload of surgeries

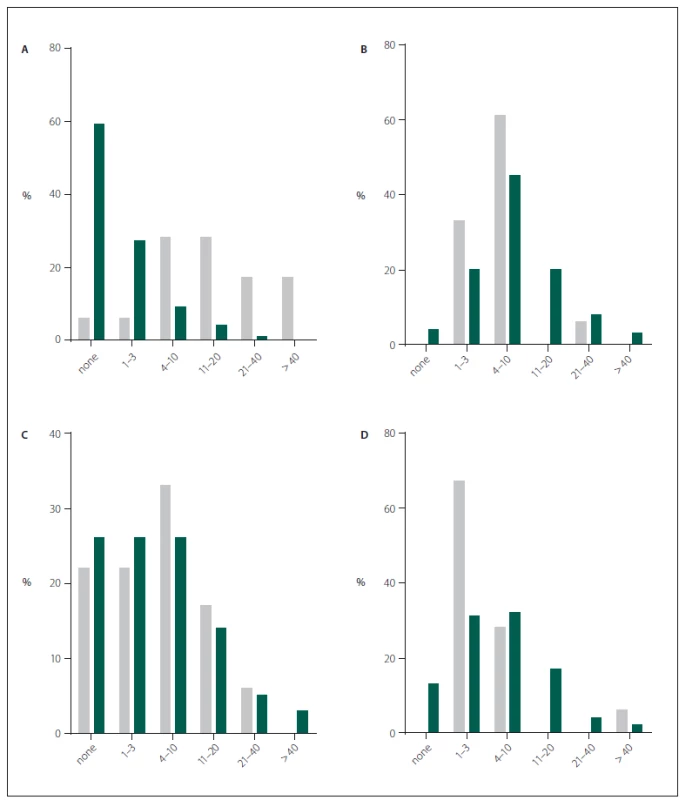

The caseload of Czech and non-Czech European resident surgeries for certain indications is displayed in Fig. 2. Czech trainees were 52-times as likely as non-Czech European trainees to perform on average ≥ 4 peripheral nerve interventions per month (OR 52.05; 11.46 – 236.31; p < 0.001). They were 13% as likely to perform on average ≥ 10 burr hole trepanations per month (OR 0.13; 0.02 – 0.97; p = 0.047), 120% as likely to perform on average ≥ 10 spinal procedures per month (OR 1.20; 0.36 – 3.93; p = 0.756), and 23% as likely to perform on average ≥ 10 craniotomies per month (OR 0.23; 0.03 – 1.83; p = 0.166).

2. Histograms depicting the average monthly caseload of 22 Czech (grey bar) and n = 510 non-Czech (green bar) European neurosurgical trainees for various neurosurgical procedures at their training facility. Fig. 2A) Peripheral nerve procedure. Fig. 2B) Burr hole trepanation. Fig. 2C) Spinal surgery (both lumbar and cervical). Fig. 2D) Craniotomy.

Working time

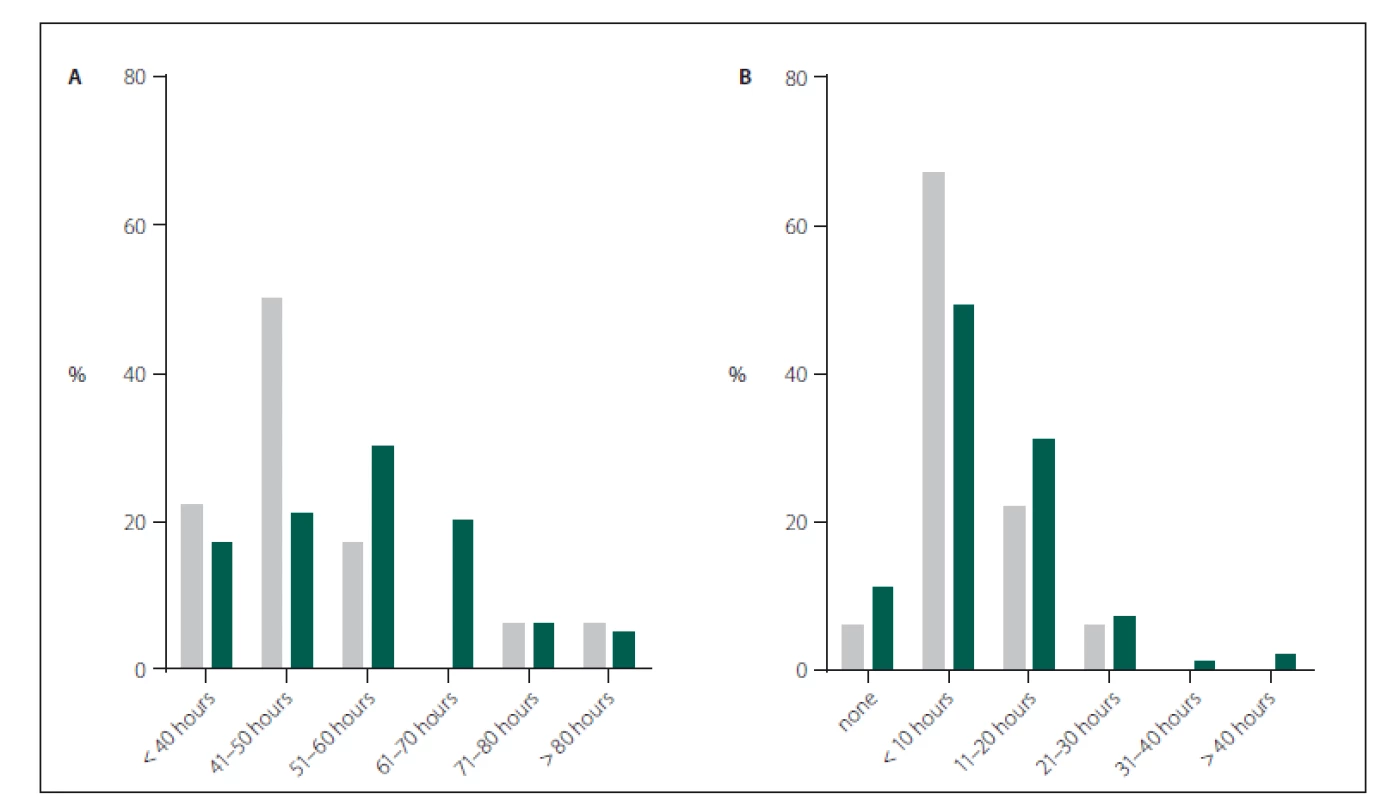

About 72% of Czech trainees currently adhere to the weekly limit of 48 h as requested by the European Working Time Directive 2003/ 88/ EC (Fig. 3A). In the international comparison, Czech trainees were 26% as likely to work > 50 h per week (OR 0.26; 0.09 – 0.75; p = 0.013). When asked about the amount of their working time, 33.3% were satisfied with the amount, 0% preferred to work fewer hours per week and 67.7% said to prefer working even more if the time was used for clinical training and not for administrative tasks. Compared to other European trainees, Czech trainees were 162% as likely to indicate wanting to work more hours (OR 1.62; 0.59 – 4.45; p = 0.346). Czech trainees were as likely to spend 50% or more of their working time in the operating theatre (OR 1.47; 0.45 – 4.80; p = 0.517) or with administrative work (OR 1.29; 0.48 – 3.45; p = 0.604). Working time for research is illustrated in Fig. 3B. The likelihood to spend > 20 h per week on scientific work was similar (OR 0.49; 0.06 – 3.86; p = 0.503).

3. Histograms demonstrating the responses of 22 Czech (grey bar) and 510 non-Czech (green bar) European neurosurgical trainees to questions concerning current working time. Fig. 3A) Hours / week spent on clinical work. Fig. 3B) Hours / week spent on scientifi c work.

Future outlook

We asked trainees whether by the end of their training they believed to be able to take over full responsibility as consultants with the training they would have received. This question was answered affirmatively by 83.3% of Czech trainees. Compared to the responses of the remaining European trainees, Czech trainees were 220% as likely to believe being able to take over full responsibility (OR 2.20; 0.62 – 7.82; p = 0.222). Lastly, we asked trainees whether they worried about their future career options. This question was equally answered affirmatively by 55.6% of Czech trainees, in line with the rate in the rest of Europe (65.7%; OR 0.71; 0.27 – 1.89; p = 0.500).

Discussion

This survey on 532 European, including 22 Czech neurosurgical trainees, sheds light on the current training situation in the CR. Results of this survey suggest that trainees are as satisfied with various aspects of theoretical training as their European colleagues. It is rather surprising that Czech trainees according to the survey are 174% as likely to be satisfied with simulator training since the availability of this type of training is rather limited.

Regarding hands-on surgical training, there was even a tendency for higher satisfaction rates among Czech residents. This effect could be explained by early hands-on surgical training as illustrated in Fig. 1. Czech neurosurgical trainees tend to be more likely to operate as a primary surgeon within the 1st year of training. They also commence relatively early with cervical spine procedures and craniotomies, when compared to the situation in the rest of Europe. Concerning the caseload of some of more frequent surgical procedures (that are likewise important for the board-certification process), there was a massively higher likelihood for Czech trainees to operate on peripheral nerves than for their colleagues from other European countries. Notably, Czech trainees were 52-times as likely to perform four or more such procedures per month. This finding probably relates to the fact that carpal tunnel syndromes are traditionally decompressed by neurosurgeons in the CR, whereas in other European countries, specialized hand-surgeons recruit these patients and thus neurosurgical trainees at university departments have less exposure during training. A considerable amount of tertiary centres nowadays offer rotation programs, where their trainees spend several weeks in a neurosurgical outpatient clinic in order to get acquainted with peripheral nerve surgery. This does not seem to be necessary in the CR. The exposition of Czech trainees to spine procedures was balanced when compared to the situation in other European countries, but it was significantly less for burr hole procedures and tended to be less for craniotomies as well. To estimate the efficacy of training, trainees were asked whether they would feel confident to have their own responsibility by the end of their training, extrapolating that their training would keep the same quality for the remaining time. Here, eight out of ten trainees were confident, and the situation corresponded to the rest of Europe.

The mentioned results confirm a decent training situation in the CR, comparable to the situation in all Europe. This is reassuring, especially when taking into consideration that countries have been identified where the training situation was below European average. This was especialy true for various aspects of theoretical and practical training in Italy [5,8], but also in Germany – a country usually perceived as one of the leading countries for high-quality neurosurgical training due to its long history, tradition, and active scientific community [7]. From the present results, no conclusions for a specific training site can be drawn as the quality of training could vary considerably between centres within a country. Taking into consideration that in 2016, there were about 61 neurosurgical trainees in the CR; this survey succeeded to reach 36% and can thus be considered representative for the country and its training sites.

It is essential to evaluate and study the current quality of neurosurgical training. Since 2000, altogether 107 neurosurgeons passed the national board exam. There are about 190 neurosurgeons in the CR. That means that more than 50% of Czech neurosurgeons passed the board exam with in the last 16 years. The quality of training is of utmost importance in respect to future neurosurgical care in the CR as well as competence of young board certified neurosurgeons to apply for a position outside the CR. It was also shown that satisfaction with the residency programme correlated with the results for the European board examination as well [9].

Concerning the clinical working time, almost three quarters of Czech trainees currently adhere to the 48-h week as requested by the European Union (EU) [6,10]. As such, Czech trainees are significantly less likely as their European colleagues to work > 50 h/ week (OR 0.25; 0.09 – 0.75; p = 0.013). This is more conforming to the law than in other EU countries, especially when compared to the situation in Germany [7,8]. Sixty-seven per cent of Czech trainees, slightly more than in other Europe n countries (about 55%), wish to work more in order to increase their surgical exposure and practical experience and about third of Czech trainees is satisfied with their working time [6]. The percentage of OR-exposure and bureau work, respectively, is balanced when compared to the situation in other European countries. The results may thus highlight that the cut-off defined by the EU may be better applicable to daily clinical routines in Czech neurosurgical departments.

Limitations and strength

The responses of a sample of 22 Czech residents helped to estimate the current training conditions, but in absence of the evaluations from those trainees who did not know about this survey or decided not to respond, generalization of the results for the whole country must be done with caution. Study groups were unbalanced for some baseline parameters (number of residents / number of yearly spine procedures), whereas we estimated the influence of these parameters on the calculated effect sizes as minor. General limitations of survey-based data such as selection bias and analytic issues have been highlighted before.

This survey is the first of its kind to enable the comparison of data from a considerable number of Czech and other European responders. Altogether, it comprises a representative cohort of trainees from the university and non-university departments throughout all postgraduate years (Table 1). Easy interpretation of results by graphic presentation and by estimating effect sizes using solid statistics facilitates the reader’s judgement. Most of the results reflect our own personal experience and reports from resident colleagues, which makes them appear valid.

Conclusions

Most of theoretical and practical aspects of neurosurgical training are rated similarly by Czech trainees when compared to the situation of trainees from other European countries. Czech neurosurgical trainees are adhering better to the 48 h-week than their colleagues from other European countries. The present results provide the opportunity for an analysis of the local conditions for each Czech training facility.

The study was supported by MO 1012.

The authors thank Amy Pinchbeck-Smith and Susie Hide from the European Association of Neurological Surgeons (EANS) for their great support with designing and distributing this survey amongst the EANS-registered residents. We furthermore thank all participating residents for their precious time and their trust.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

Accepted for review: 6. 9. 2017

Accepted for print: 23. 11. 2017

doc. MUDr. David Netuka, Ph.D.

Neurochirurgická a neuroonkologická klinika 1. LF UK a ÚVN - VFN Praha

U Vojenské nemocnice 1200

169 02 Praha 6

e-mail: david.netuka@uvn.cz

Sources

1. Burkhardt JK, Zinn PO, Bozinov O et al. Neurosurgical education in Europe and the United States of America. Neurosurg Rev 2010; 33(4): 409–417. doi: 10.1007/ s10143-010-0257-6.

2. Izquierdo JM. A programme of neurosurgical education. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1990; 107(3-4): 171–178.

3. Long DM, European Union of Medical S. The ideal neurosurgical training curriculum. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2004; 90 : 21–31.

4. Omerhodzic I, Tonge M, Matos B et al. Neurosurgical training programme in selected European countries: from the young neurosurgeons‘ point of view. Turk Neurosurg 2012; 22(3): 286–293. doi: 10.5137/ 1019–5149.

5. Stienen MN, Netuka D, Demetriades AK et al. Neurosurgical resident education in Europe-results of a multinational survey. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2016; 158(1): 3–15. doi: 10.1007/ s00701-015-2632-0.

6. Stienen MN, Netuka D, Demetriades AK et al. Working time of neurosurgical residents in Europe – results of a multinational survey. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2016; 158(1): 17–25. doi: 10.1007/ s00701-015-2633-z.

7. Stienen MN, Gempt J, Gautschi OP et al. Neurosurgical resident training in Germany. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg 2017; 78(4): 337–343. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1594012.

8. Brennum J. European neurosurgical education – the next generation. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2000; 142(10): 1081–1087.

9. Stienen MN, Netuka D, Demetriades AK et al. Residency program trainee-satisfaction correlate with results of the European board examination in neurosurgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2016; 158(10): 1823–1830. doi: 10.1007/ s00701-016-2917-y.

10. Schaller K. Neurosurgical training under European law. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2013; 155(3): 547. doi: 10.1007/ s00701-012-1579-7.

Labels

Paediatric neurology Neurosurgery Neurology

Article was published inCzech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

2018 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- Injury as a cause of extrapyramidal syndrome

- Injury as a cause of extrapyramidal syndromes

- Injury as a cause of extrapyramidal syndromes Comment on controversies

- Olfactory groove meningiomas – surgical treatment, surgical risks and sense of smell preservation

- Neuropalliative and rehabilitative care in patients with an advanced stage of progressive neurological diseases

- Protective factors for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis

- Assessment of cognitive functions using short repeatable neuropsychological batteries

- Test of gestures (TEGEST) for a brief examination of episodic memory in mild cognitive impairment

- The importance of morphological and clinical classifications of lumbar spine stenosis in the preoperative planning

- Parosmia and phantosmia in patients with olfactory dysfunction

- SCN1A mutation positive Dravet syndrome, genetic aspects and clinical experiences

- Sentence comprehension in Slovak-speaking patients with Parkinson disease

- The pilot study of effect of outpatient functional electrical stimulation of peroneal nerve

- A neurological view on spondylodiscitis

- Statins and their effects on the peripheral nervous system

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis – still occurring complication of rhinosinusitis

- T1 radiculopathy due to massive disc herniation at T1/2

- Neuropathological post-mortem examination of the brain and the spinal cord in ten key points – What can a neurologist expect from the neuropathologist’s confirmation of the clinical diagnosis in neurodegenerative diseases?

- Long-term follow up of a patient with primary cervical spinal cord meningeal melanocytoma

- Neurosurgical resident training in the Czech Republic

- Alternative forms parallel to the Czech versions of Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, Complex Figure Test and Verbal Fluency

- Leiomyoma of the palm

- Dural-based posterior fossa giant cavernous hemangioma masquerading as hemangiopericytoma

- Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- A neurological view on spondylodiscitis

- Parosmia and phantosmia in patients with olfactory dysfunction

- Assessment of cognitive functions using short repeatable neuropsychological batteries

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis – still occurring complication of rhinosinusitis

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career