-

Medical journals

- Career

Existence primární pediatrické péče v Německu ohrožena

Authors: E. Jaeger-Roman

Published in: Čes-slov Pediat 2009; 64 (5): 257-258.

Category: Actual Topic

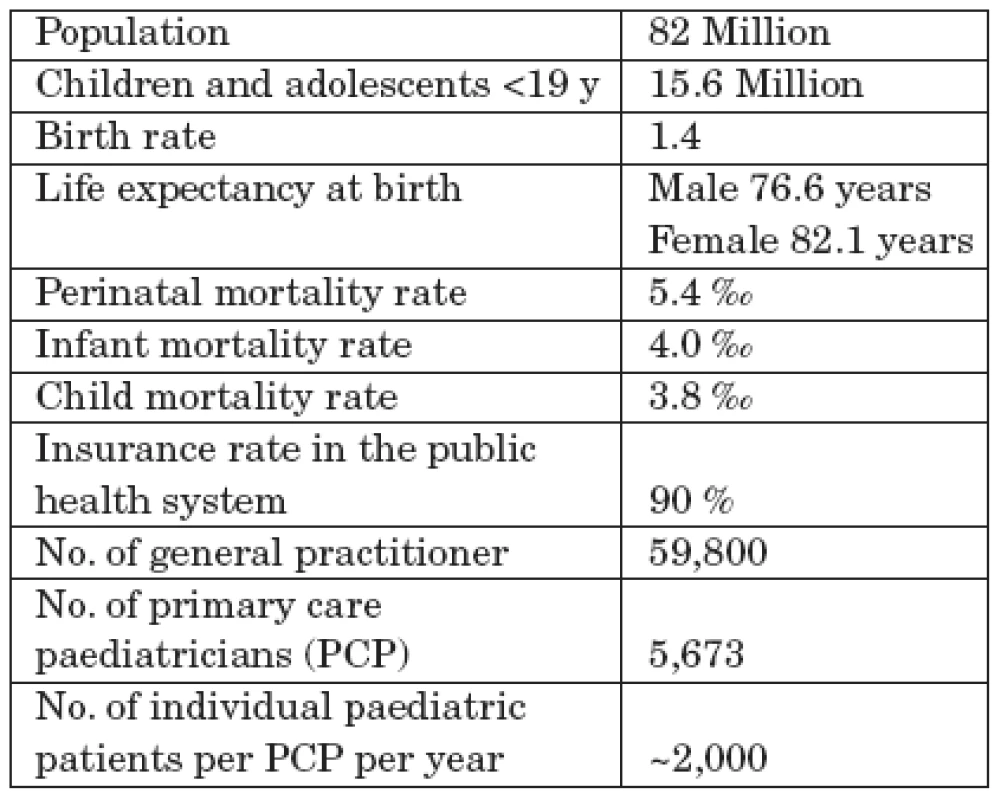

Children and adolescents up to the age of 18 have been traditionally cared for in Germany by a mixed system of primary care paediatricians (PCP’s) and general practitioners (GP’s). In the cities, most children and adolescents stay with their PCP through adolescence, but in country areas, children as they get older, are increasingly seen by GP’s. Children and adolescents with special needs are cared for by a tight network of PCP in private practices plus sub-specialists in tertiary centres. Demographic basic information is presented in Tab. 1.

Table 1. Some Basic Information on Demographic Data and the Health System in Germany.

The general paediatric postgraduate training program (5 years) has been adapted according to the recommendations of the European Board of Paediatrics (Union of European Medical Specialists – Paediatric Section). There are 9 paediatric sub-specialities, each requiring 2 to 3 years of additional training in a tertiary centre. 70% of the PCP’s work alone and 30 % in group practices. Practices are for the most part technically well equipped for growth - and development diagnostics, for the diagnosis of acutely sick children with a basic laboratory, and with ultrasonic equipment, spirometry, ECG etc.

90% of practices use computers partially - or exclusively to keep the medical records.

As in most European countries, german paediatrics has undergone major changes in the last decades: demographic change (decreasing number of children), changes in the spectrum of paediatric illnesses (less severe infectious - but “new” paediatric diseases), a better survival rate of chronically ill children and an ever increasing number of children who are cared for mainly in the ambulatory setting. These developments have resulted in children’s hospitals becoming less in number and smaller in size, i.e. the number of beds and length of stay of children have decreased dramatically. As a consequence, paediatric training positions in children’s hospitals have also dropped substantially. Unfortunately, alternative training positions can not be set up in paediatric practices because they are not paid for. This results in a lack of a sufficient number of newly trained and an aging of practising PCP’s. Furthermore, the trend of feminization in paediatrics continues. Although this has no effect on the quality of the profession but does however influence working hours. Women place more value on the compatibility of profession and family, work more often part time and are less inclined to work outside surgery hours. In the future, all these trends will most probably put in danger a comprehensive care of children and adolescents by PCP’s.

A special problem in the german mixed PCP/GP system is the lack of basic training of GP’s in the field of paediatrics. GP’s are not required to do any training in paediatrics at all. Consequently, most GP’s only come in contact with paediatric patients when they start their own practices. Recently, some have claimed publicly that this “learning-by-doing” approach is sufficient to deal with children. When GP’s require a second opinion, they tend to send their child patients to children’s hospitals and not to their fellow (neighbour) PCP’s. Hence, there exists a system of competing rivalry and not one of mutual support.

Independent of these demographic-structural problems, new german legislation to restructure the health system is having a disastrous effect on the interests of paediatric primary care. It is an avowed aim of the minister of health to strengthen the role of the GP’s in primary care. Health funds have now been assigned a central role. They must negotiate health care contracts with GP’s so that these can function as “gatekeepers”. Patients have no more free access to other ambulatory doctors. Paediatricians were also affected by this regulation but massive lobbying forced the legislators to grant an exemption giving parents again free access to PCP’s.

Expenditure of the health funds for ambulatory medical care is globally budgeted.

PCP’s and GP’s have a common budget. The delegates of the German Physicians Association (with paediatricians being outnumbered and without minority protection) frame the rules as to how this budget is distributed amongst primary care doctors. Budgeting also applies individually to doctor’s fees, medical prescriptions, ergo - and speech therapy and physiotherapy. The aim of the changes to the health legislation is the strict control of the costs through rationalization and through competition of the various health funds and the doctors with one another. Regrettably, the existing health laws do not formulate any targets for sustaining good health through health promotion and primary preventive measures nor do they specify any criteria for the good medical care of children and adolescents.

Address for Correspondence:

Dr. med. Elke Jaeger-Roman

Prof. Dr. med. Hans-Jürgen Nentwich,

Secretary General

Deutsche Akademie für Kinder -

und Jugendmedizin e.V.

Chausseestr. 128/129

10115 Berlin

Germany

e-Mail: kontakt@dakj.de

Internet: www.dakj.de

Labels

Neonatology Paediatrics General practitioner for children and adolescents

Article was published inCzech-Slovak Pediatrics

2009 Issue 5-

All articles in this issue

- Molekulová diagnostika dedičných nekonjugovaných hyperbilirubinémií na Slovensku

- Akutní neuroboreliózy u dětí

- Standardy multidisciplinární péče o dítě s rozštěpem obličeje

- Děti a mládež na počátku mediální a informační společnosti

- Současné trendy v diagnostice fetálního alkoholového syndromu

- Existence primární pediatrické péče v Německu ohrožena

- Czech-Slovak Pediatrics

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Akutní neuroboreliózy u dětí

- Současné trendy v diagnostice fetálního alkoholového syndromu

- Molekulová diagnostika dedičných nekonjugovaných hyperbilirubinémií na Slovensku

- Standardy multidisciplinární péče o dítě s rozštěpem obličeje

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career