-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Analysis of fatal industrial accidents in forensic postmortem investigations in South Osaka

Analýza fatálních industriálních nehod v soudnělékařském zkoumání v oblasti jižní Osaky

Předkládaná studie zkoumala aktuální stav a příčiny smrtelných pracovních úrazů ze zdravotně-sociálního hlediska. Retrospektivně jsme hodnotili případy smrtelných pracovních úrazů mezi lety 2007 a 2016 v Ósace, která je druhým nejlidnatějším městem v Japonsku, z forenzních posmrtných dat 1689 zemřelých. Z těchto případů jsme analyzovali celkem 57 smrtelných průmyslových nehod. Oběťmi byli typicky muži v relativně pokročilém věku pracující generace, téměř polovina případů (přesněji 28) byli muži mezi 50 a 70 lety života. Nejčastějším typem nehody byl pád z výše (24 případů) a nejčastějším místem, kde k nehodám docházelo, bylo staveniště (28 případů). Většina nehod (29 případů) se odehrála na pracovišti s malým pracovním týmem. V 60 % případů oběť na sobě neměla ochranou helmu a ve 34 případech (60 %) byla nehoda připisována vlastní nedbalosti. Nehody se nejčastěji stávaly v úterý. Nejběžnější doba, kdy k nehodám docházelo, byla kolem 10. a 11. hodiny dopolední a kolem 1. a 2. hodiny odpolední. V přibližně 60 % případů žaludeční obsah zahrnoval i zbytky potravy, což naznačuje, že k nehodám typicky docházelo po jídle. V předkládané studii jsme zjistili, že pracovní nehody, z nichž nejčastější byl pád z výše, vykazují tendenci se vyskytovat na pracovišti s malým pracovním týmem. Pouze pár obětí mělo na sobě ochranou helmu. Tato zjištění naznačují, že na pracovištích by měly být důkladně zaváděny systémy monitorování a řízení bezpečnosti a že pracovníci by měli před i po jídle dbát zvýšené opatrnosti.

Klíčová slova:

forenzní – zdravotně-sociální hledisko – průmyslové nehody – továrna – staveniště

Authors: Tani Naoto 1,2; Ikeda Tomoya 1,2; Oritani Shigeki 1; Morioka Fumiya 1; Ikeda Kei 1; Shida Alissa 1; Aoki Yayoi 1; Ishikawa Takaki 1,2

Authors place of work: Department of Legal Medicine, Osaka City University Medical School, Osaka, Japan 1; Forensic Autopsy Section, Medico-legal Consultation and Postmortem Investigation Support Center, c/o Department of Legal Medicine, Osaka City University Medical School, Osaka, Japan 2

Published in the journal: Soud Lék., 65, 2020, No. 3, p. 56-60

Category: Original article

Summary

Předkládaná studie zkoumala aktuální stav a příčiny smrtelných pracovních úrazů ze zdravotně-sociálního hlediska. Retrospektivně jsme hodnotili případy smrtelných pracovních úrazů mezi lety 2007 a 2016 v Ósace, která je druhým nejlidnatějším městem v Japonsku, z forenzních posmrtných dat 1689 zemřelých. Z těchto případů jsme analyzovali celkem 57 smrtelných průmyslových nehod. Oběťmi byli typicky muži v relativně pokročilém věku pracující generace, téměř polovina případů (přesněji 28) byli muži mezi 50 a 70 lety života. Nejčastějším typem nehody byl pád z výše (24 případů) a nejčastějším místem, kde k nehodám docházelo, bylo staveniště (28 případů). Většina nehod (29 případů) se odehrála na pracovišti s malým pracovním týmem. V 60 % případů oběť na sobě neměla ochranou helmu a ve 34 případech (60 %) byla nehoda připisována vlastní nedbalosti. Nehody se nejčastěji stávaly v úterý. Nejběžnější doba, kdy k nehodám docházelo, byla kolem 10. a 11. hodiny dopolední a kolem 1. a 2. hodiny odpolední. V přibližně 60 % případů žaludeční obsah zahrnoval i zbytky potravy, což naznačuje, že k nehodám typicky docházelo po jídle. V předkládané studii jsme zjistili, že pracovní nehody, z nichž nejčastější byl pád z výše, vykazují tendenci se vyskytovat na pracovišti s malým pracovním týmem. Pouze pár obětí mělo na sobě ochranou helmu. Tato zjištění naznačují, že na pracovištích by měly být důkladně zaváděny systémy monitorování a řízení bezpečnosti a že pracovníci by měli před i po jídle dbát zvýšené opatrnosti.

Keywords:

forensic – sociomedical perspective – industrial accidents – factory – construction site

Industrial accidents occur frequently in Japan and throughout the world, especially at factories and construction sites (1). In 2007, there were a total of 121,356 industrial accidents in Japan, including 1,357 fatalities, whereas in 2016, there were a total of 117,910 industrial accidents, including 928 fatalities. Although the incidence of industrial accidents has been decreasing, approximately 1,000 confirmed fatalities are still reported every year (2).

Osaka is the second most populous city in Japan, with approximately 2.7 million residents (as of October 1, 2016) (3). The southern part of Osaka accounts for approximately 43.1 % (1.1 million) of the city’s population, and a higher ratio of day laborers have traditionally lived in this area (4). Osaka is located in the center of an area called the Hanshin Industrial Region and contributes greatly to the Japanese secondary industry sector (e.g., manufacturing, construction, electricity, and gas industries) (5). However, on average, there are 19.7 industrial accident-related deaths per year across all of Japan. Whereas in Osaka in 2016, 51 industrial accident-related deaths were reported (1). Therefore, many more people are involved in fatal occupational accidents in Osaka than in other areas across Japan.

In the field of forensic medicine, it has been reported that industrial accidents often involve homicide and corporate manslaughter (6-10). When fatal industrial accidents occur in Japan, a forensic autopsy is required to clarify whether homicide or corporate manslaughter were involved. A previous study in Osaka reported that industrial accidents were in most cases considered to be the result of carelessness and the fault of coworkers or the workers themselves, without any predispositions, including disease or alcohol and drug abuse (11). However, only a few reports have examined the background factors that may contribute to industrial accidents from a sociomedical perspective in forensic autopsy cases (12,13). In addition, in that previous study, the characteristics and causes that may help explain why coworkers or the workers themselves were careless and at fault were not investigated (11). Therefore, in the present study, we examined the current status, characteristics, and causes of industrial accidents from a sociomedical perspective. In addition, we investigated the causes of fatal work-related accidents that occurred at a factory and construction site and examined precautionary measures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection

Fatal industrial accidents were retrospectively investigated from the forensic postmortem data of 1,689 decedents between 2007 and 2016 in the south Osaka area (our forensic autopsy department). Of these cases, 57 were found to be labor-related fatalities. Next, we analyzed these 57 fatalities from a medical viewpoint. In particular, we investigated the victims in factories and construction sites to clarify the cause of industrial accidents in the secondary industry sector. Regarding work-related accidents in general in Japan, forensic autopsies are carried out to investigate whether professional negligence on the part of the company is involved in such fatalities.

For each fatal accident, data were obtained on the victim’s age, sex, reason for commissioned autopsy, type of accident, cause of death, use of personal protective equipment, type of industry, cause of accident, course from injury until death, time of accident, gastric contents, alcohol concentration, and drug intake, as well as the annual incidence of fatalities and the number of workers in the industrial facility.

Data analysis

Causes of death were classified according to the findings of complete autopsies and macromorphological, micropathological, and toxicological examinations (14). Sample information was collected based on postmortem pathological and chemical findings and criminal investigations. Blood alcohol levels were determined by headspace gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (15), and drug analyses were performed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (16). The information was stored in a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) database and submitted for statistical analysis. The results of quantitative and qualitative variables are described as percentages.

RESULTS

Annual incidence

Among 1,689 forensic postmortem cases, 57 (3.4 %) were labor-related fatalities, showing a varied annual incidence of 10, 3, 3, 9, 7, 1, 9, 5, 5, and 5 cases from 2007 to 2016, respectively, or an average of approximately five cases per year.

Age and sex

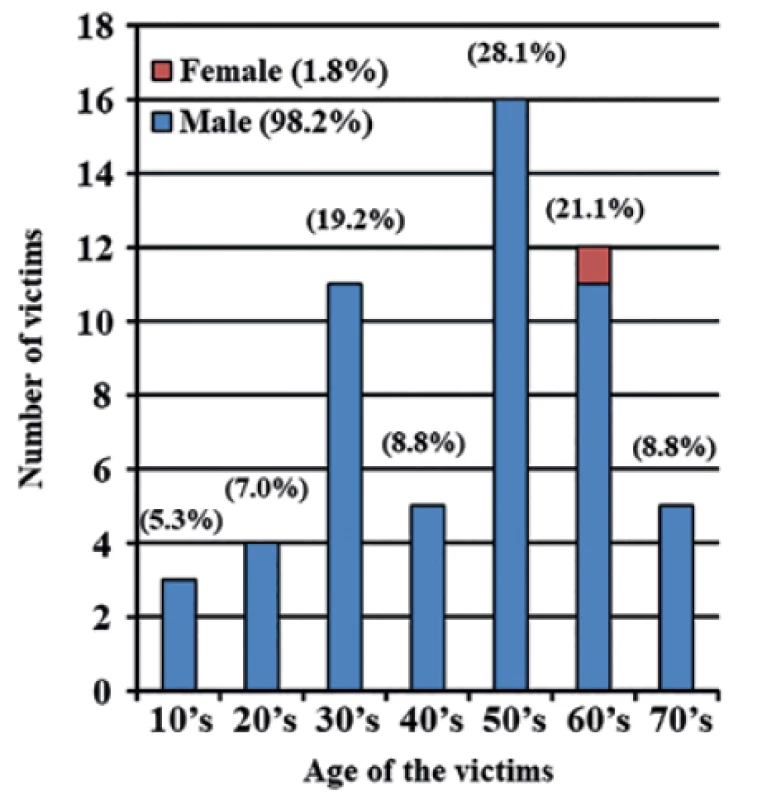

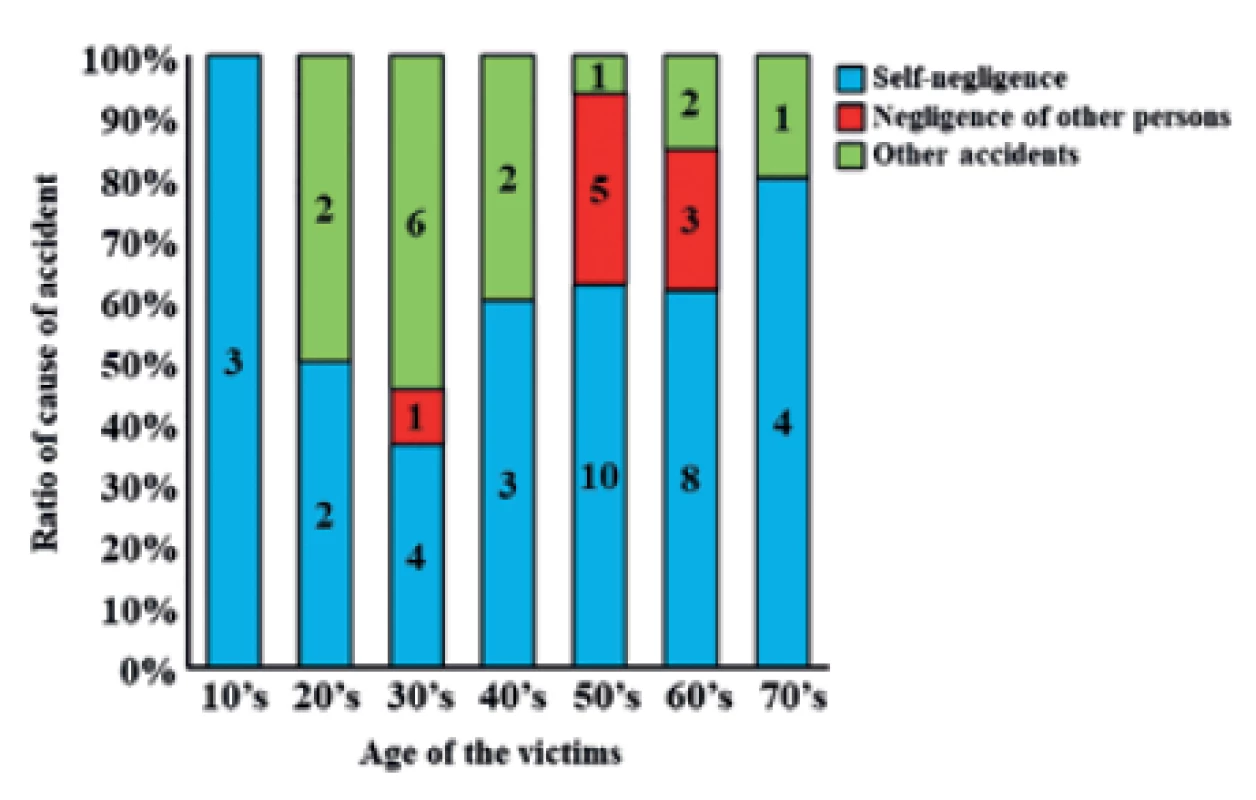

Fifty-six (98.2 %) victims were male and one (1.8 %) was female. The age of the victims ranged from 17 to 76 y, with a median of 52 y. Three (5.3 %) victims were in their teens, four (7.0 %) in their 20s, 11 (19.2 %) in their 30s, five (8.8 %) in their 40s, 16 (28.1 %) in their 50s, 12 (21.1 %) in their 60s, and five (8.8 %) in their 70s. Accidents were more common among those in their 50s and 60s, with a total of 28 cases (49.2 %) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Age-specific labor-related fatalities (n = 57).

Reason for the commissioned autopsy

The reason for the commissioned autopsy included suspected corporate manslaughter (30 cases; 52.6 %) and suspected homicide (27 cases; 47.4 %). Suspected homicide and corporate manslaughter accounted for approximately half of all cases. However, based on forensic autopsies, no homicide cases were identified.

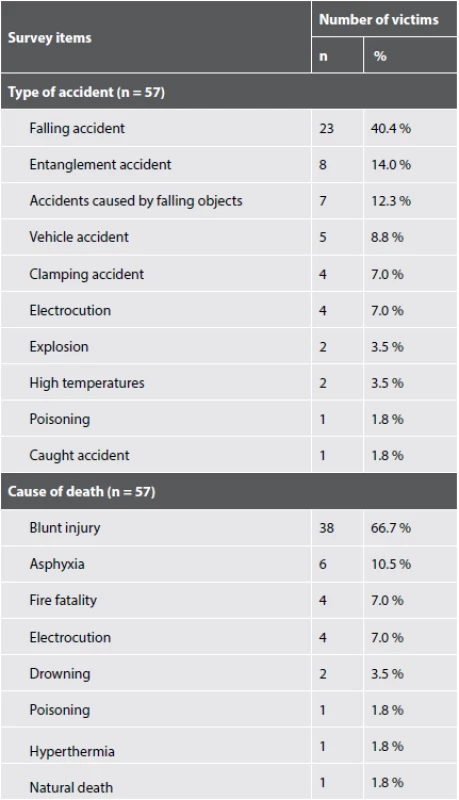

Type of accident

The most common type of accident was falling (23 cases; 40.4 %), followed by entanglement (8 cases; 14.0 %), falling objects (7 cases; 12 %), vehicle accidents (5 cases; 8.8 %), clamping (4 cases; 7.0 %), electrocution (4 cases; 7.0 %), explosions (2 cases; 3.5 %), high temperatures (2 cases; 3.5 %), poisoning (1 case; 1.8 %), and trapped in machinery (1 case; 1.8 %) (Tab. 1).

Tab. 1. Type of accidents and cause of death in labor-related fatalities.

n, number of patients Cause of death

The most common cause of death was blunt injury (38 cases; 66.7 %). Of the fatalities caused by blunt injury, 11 (28.9 %) were due to head injuries, eight (14.0 %) to chest injuries, six (10.5 %) to head and chest injuries, five (8.8 %) to chest and abdomen injuries, four (7.0 %) to neck injuries, two (3.5 %) to abdominal injuries, and two (3.5 %) to lumbar injuries. In the case of death due to head injury, only 3 cases were acute death after injury, 8 cases died due to brain contusion and prolonged central nervous dysfunction after a few hours to a few days after injury.

Causes of death other than blunt injury were asphyxia (6 cases; 10.5 %), fire (4 cases; 7.0 %), electrocution (4 cases; 7.0 %), drowning (2 cases; 3.5 %), poisoning due to trichlorethylene (1 case; 1.8 %), hyperthermia (1 case; 1.8 %), and natural death (acute cardiac death) (1 case; 1.8 %) (Tab. 1). Among the asphyxia cases, five involved thoracic movement disorders due to thoracic compression and one involved clothing being inserted between a machine that strangled the neck.

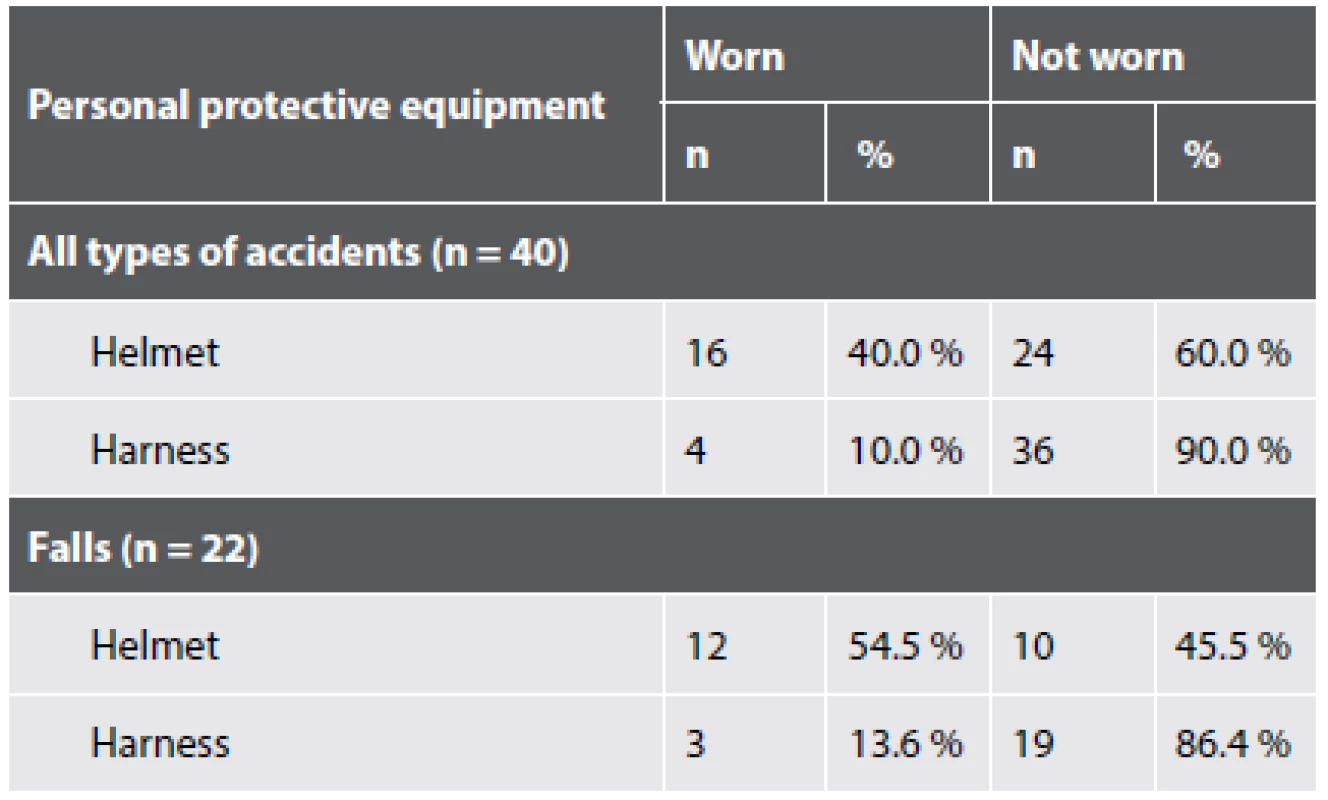

Personal protective equipment

Among the 40 cases for which it was known whether the victim was wearing personal protective equipment, a helmet was worn in 16 (40.0 %) and not worn in 24 (60.0 %). Among the 22 cases of fatal falls for which it was known whether the victim was wearing protective equipment, a helmet was worn in 12 (54.5 %) and not worn in 10 (45.5 %). In addition, a harness was worn in three cases (13.9 %) and not worn in 19 (86.4 %) (Tab. 2).

Tab. 2. Use of personal protective equipment in labor-related fatalities.

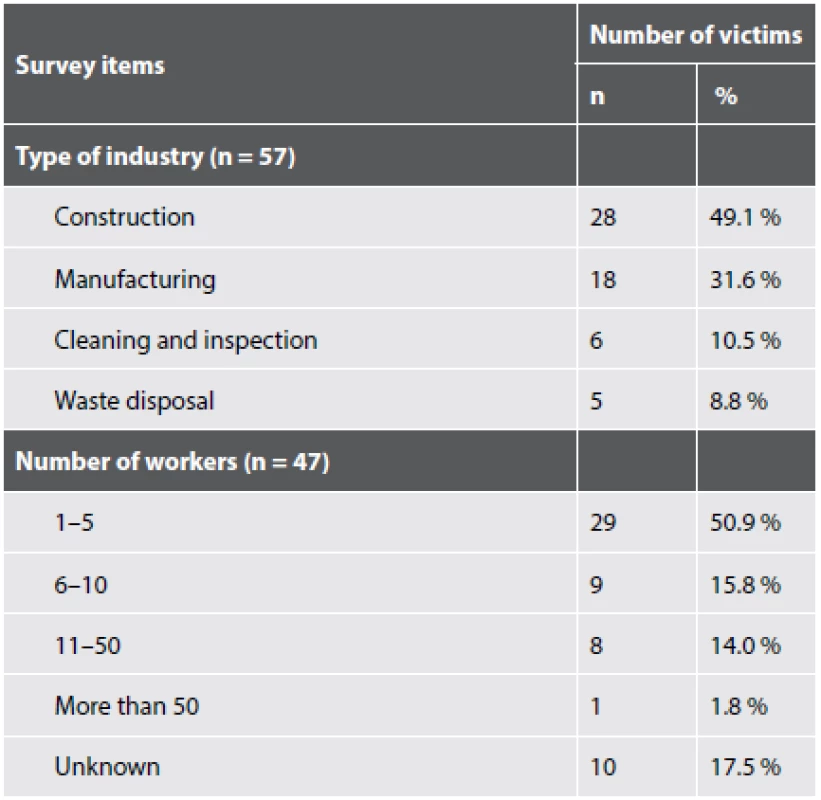

n, number of patients Type of industry and number of workers

The most frequent type of industry in which fatal accidents occurred was the construction industry (28 cases; 49.1 %), followed by the manufacturing industry (18 cases; 31.6 %), the cleaning and inspection industry (6 cases; 10.5 %), and the waste disposal industry (5 cases; 8.8 %). Among the 47 cases for which the number of workers in the facility was known, worksites with a small number of approximately one to five workers were the most frequent (29 cases; 61.7 %), followed by sites with six to 10 workers (9 cases; 19.1 %), 11 to 50 workers (8 cases; 17.0 %), and more than 50 workers (1 case; 2.1 %) (Tab. 3).

Tab. 3. Type of industry and number of workers in labor-related fatalities.

n, number of patients Causes of accidents

The causes of the accidents were self-negligence (34 cases; 60 %), negligence by other persons (9 cases; 16 %), and other causes (14 cases; 24 %). In the present study, negligence was determined according to whether the accident victim could have prevented the accident from occurring through self-safety management. Occurrences arising from the neglect of safety management were considered to be “self-neglect”, whereas those arising from operational mistakes or the inattention of other persons were considered to be “negligence of others”. Other causes involved a collapsed scaffolding or malfunctioning machinery. All fatal accidents in people in their teens were the result of self-negligence. The rate of death from self-negligence decreased somewhat for people in their 20s and 30s and increased with age from the 40s, ultimately accounting for 80 % of deaths of people in their 70s (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Cause of accidents in labor-related fatalities (n = 57).

Course from injury until death

Acute death occurred in 34 cases (59.6 %), subacute death in 10 (17.5 %), and prolonged death in 13 (22.8 %). Fifty-four victims (94.7 %) were transported to the hospital. Among these, eight (14.8 %) were conscious at the time of transportation, 35 (64.8 %) were in a state of cardiopulmonary arrest, and 11 (20.4 %) were unconscious. Twenty victims (37.0 %) were admitted to the hospital. Although almost all victims were transported to the hospital, most died without being resuscitated.

Time of accidents

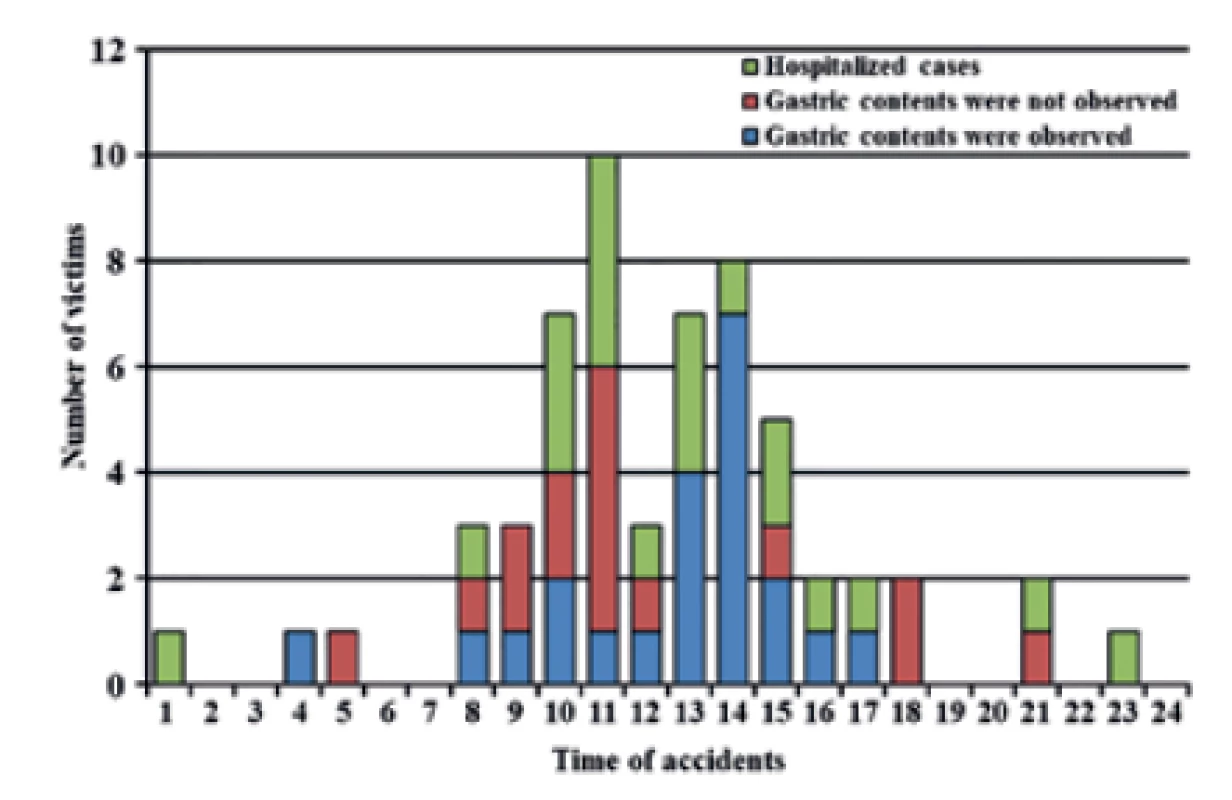

Seven accidents (12.3 %) occurred on a Monday, 18 (31.5 %) on a Tuesday, five (8.8 %) on a Wednesday, five (8.8 %) on a Thursday, 12 (21.1 %) on a Friday, seven (12.3 %) on a Saturday, and three (5.3 %) on a Sunday. One accident (1.8 %) occurred at around 1 am, one (1.8 %) at around 4 am, one (1.8 %) at around 5 am, three (5.3 %) at around 8 am, two (3.5 %) at around 9 am, seven (12.3 %) at around 10 am, 10 (17.5 %) at around 11 am, three (5.3 %) at around 12 pm, seven (12.3 %) at around 1 pm, eight (14.0 %) at around 2 pm, five (8.8 %) at around 3 pm, two (3.5 %) at around 4 pm, two (3.5 %) at around 5 pm, two (3.5 %) at around 6 pm, two (3.5 %) at around 9 pm, and one (1.8 %) at around 11 pm. The day on which accidents occurred most frequently was Tuesday. The time of accident was around 10 to 11 am in 29.8 % of the cases and around 1 to 2 pm in 28.3 % of the cases (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Time of accident and presence of gastric contents in labor-related fatalities.

Gastric contents

Of the 37 cases, excluding the hospitalized cases, the gastric contents showed food residue in 22 (59.5 %) and no food residue in 15 (40.5 %). Food residue was observed in all victims who had died around 1 to 2 pm. The volume of the gastric contents was most commonly less than 25 mL (15 cases; 40.5 %), 25–50 mL (16 cases; 16.2 %), 100 mL (13 cases; 8.1 %), approximately 200 mL (12 cases; 5.4 %), approximately 300 mL (11 cases; 2.7 %), approximately 400 mL (17 cases; 18.9 %), approximately 500 mL (11 cases; 2.7 %), and approximately 600 mL (2 cases; 5.4 %) (Fig. 3).

Alcohol concentration

Among the 48 cases with measurable alcohol concentrations in right heart blood within 2 days postmortem, alcohol was detected in two (4.2 %). The alcohol concentrations were 0.26 mg/mL (mild intoxication) and 1.25 mg/mL (moderate intoxication) (17). In these cases, drinking alcohol during and/or prior to working may have affected the risk of having an accident.

Drugs

Measurable drug concentrations in samples of right endocardial blood were noted in nine cases (32.1 %), excluding fatalities after hospitalization. Among these nine cases, the occurrences and levels of the drugs were as follows: lidocaine in nine cases (0.142–7.71 ìg/mL), acetaminophen in two (0.350–1.59 ìg/mL), dihydrocodeine in one (0.023 ìg/mL), diphenhydramine in one (0.013 ìg/mL), midazolam in two (0.058–1.74 ìg/mL), diazepam in one (0.022 ìg/mL), and clomipramine in one (0.085 µg/mL). All detected drugs were under therapeutic ranges (18).

DISCUSSION

In Japan, the annual number of fatal industrial accidents has been gradually declining. However, in the south Osaka area, no decrease has been observed in the number of labor-related fatalities. When an autopsy is performed in Japan, the reason for the autopsy must be listed with the court of justice. In the present study, suspected homicide and corporate manslaughter accounted for approximately half of all cases. However, as a result of forensic autopsies, no homicide cases were identified. These results suggest that the purpose of forensic autopsies needs to be clarified.

Most victims were males in their 50s and 60s. Most workers in Japan are in their 30s, 50s, or 60s, and the number of labor-related fatalities increases with age. We observed a similar tendency in the present study. Workers in their 50s and 60s often have a long employment history, and among such experienced workers, accidents frequently occur. The most common cause of death was blunt injury, often to the head, resulting from a fall. However, because there many prolonged deaths and the damage is not so severe, it can be presumed that cases involving head injuries may be prevented with the use of a helmet. Among the workers who died from falls, about half were not wearing a helmet and about 80 % were not wearing a safety harness. The most frequent location of fatal accidents were construction sites with small numbers of workers. These results suggest the importance of safety management at such sites (19-21). In addition, self-negligence was frequent, particularly among younger and older workers. These findings suggest that workers in these age groups tend to neglect safety management (22).

Furthermore, accidents frequently occurred before lunch break at around 10 to 11 am and after lunch break at around 1 to 2 pm. The workday in Japan generally ends at 5 pm, so few accidents occurred after that time. Similar to the present study, several studies have reported that accidents commonly occur around 10 to 11 am and around 1 to 2 pm (23-25). In the present study, food residue was frequently found in the stomachs of workers who had been involved in an accident around 1 to 2 pm, which suggests that accident risk is increased after a meal. Therefore, worker should be careful when working immediately after meals.

In recent years, the disturbance of daily life rhythms because of night work has become a social problem (26,27). In the present study, we observed cases of labor-related fatalities during the night shift. Good safety management and the maintenance of a good physical condition are important for people working at night. Because alcohol was detected in two cases, drinking alcohol during and/or prior to work may have affected the risk of accidents. Toxicological examinations revealed that all of the drugs detected were under the therapeutic range. However, it is important to provide thorough education on safety management regarding alcohol and drugs.

This study did have some limitations. For example, some information was based on documents from the police, which in some cases had missing details. Approximately 1,000 fatal occupational accidents occur every year in Japan, and the south Osaka area accounts for only a small proportion of them. Therefore, comparative studies of industrial accidents in other areas are needed.

The results of the present study showed that advanced age, a small working team, neglected safety management, and working after a meal were related to fatal industrial accidents, especially from falls. The descriptive results suggest that these factors affected the carelessness and fault of the coworkers and/or workers themselves. Therefore, a thorough review of on-site safety management and monitoring systems is needed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

∗ Correspondence address:

Naoto Tani

Department of Legal Medicine,

Osaka City University Medical School,

Asahi-machi 1-4-3, Abeno, 545-8585 Osaka, Japan.

tel.: 81-6-6645-3767; fax: 81-6-6634-3871

e-mail: tani.naoto@med.osaka-cu.ac.jp

Received: October 23, 2019

Accepted: April 10, 2020

Zdroje

Iizuka T, Randell T, Güven O, Lindquist C. Maxillofacial fractures related to work accidents. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1990; 18 : 255–259.

Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [homepage on the Internet]. Occurrence of the industrial accident; 2016. [uploaded 2017; cited 2018 Aug 7] Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/roudoukijun/anzeneisei11/rousai-hassei/. (Japanese)

Kajino K, Kitamura T, Iwami T, Daya M, Ong ME, Nishiyama C, et al. Impact of the number of on-scene emergency life-saving technicians and outcomes from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Osaka City. Resuscitation 2014; 85 : 59–64.

Tabuchi T, Takatorige T, Hirayama Y, Nakata N, Harihara S, Shimouchi A, et al. Tuberculosis infection among homeless persons and caregivers in a high-tuberculosis-prevalence area in Japan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11 : 22.

Edgington DW. City profile: Osaka. Cities 2000; 17 : 305–318.

Yamamoto T, Takasu K, Emoto Y, Shikata N, Matoba R. Case report of death from falling: Did heart tumor cause syncope? Int J Legal Med 2012; 126 : 633–636.

Furumiya J, Nishimura H, Nakanishi A, Hashimoto Y. Postmortem endogenous ethanol production and diffusion from the lung due to aspiration of wood chip dust in the work place. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2011; 13 : 210–212.

Takase I, Kono K, Tamura A, Nishio H, Dote T, Suzuki K. Fatality due to acute fluoride poisoning in the workplace. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2004; 6 : 197–200.

Jayanth SH, Hugar BS, Chandra YP, Krishnan AG. Fatal head injury: a sequelae to electric shock - a case report. Med Leg J 2015; 83 : 47–50.

Takamiya M, Niitsu H, Saigusa K, Kanetake J, Aoki Y. A case of acute gasoline intoxication at the scene of washing a petrol tank. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2003; 5 : 165–169.

Maeda H, Fujita MQ, Zhu BL, Quan L, Kamikodai Y, Tsuda K, et al. Labor-related fatalities in forensic postmortem investigations during the past 6 years in the southern half of Osaka city and surrounding areas. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2003; Suppl 1: S325–327.

Khodabandeh F, Kabir-Mokamelkhah E, Kahani M. Factors associated with the severity of fatal accidents in construction workers. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2016; 30 : 469.

Hashimoto Y. Occupational health from medicolegal point of views: based on 25 cases of postmortem examination in our department. Res Pract Forens Med 2012; 55 : 1–19.

Tani N, Ikeda T, Oritani S, Michiue T, Ishikawa T. Role of circadian clock genes in sudden cardiac death: a pilot study. J Hard Tissue Biol 2017; 26 : 347–354.

Maeda H, Zhu BL, Ishikawa T, Oritani S, Michiue T, Li DR, et al. Evaluation of post-mortem ethanol concentrations in pericardial fluid and bone marrow aspirate. Forensic Sci Int 2006; 161 : 141–143.

Tominaga M, Michiue T, Oritani S, Ishikawa T, Maeda H. Evaluation of postmortem drug concentrations in bile compared with blood and urine in forensic autopsy cases. J Anal Toxicol 2016; 40 : 367–373.

Kinoshita H, Ameno K, Jamal M. Ethanol, methanol and toluene. Forensic Pathology 2009; 15 : 37–44.

Winek CL, Wahba WW, Winek CL Jr, Balzer TW. Drug and chemical blood-level data 2001. Forensic Sci Int 2001; 122 : 107–123.

Ohdo K, Hino Y, Takahashi H. Research on fall prevention and protection from heights in Japan. Ind Health 2014; 52 : 399–406.

Hsiao HW. Fall prevention research and practice: a total worker safety approach. Ind Health 2014; 52 : 381–392.

Hino Y, Ohdo K, Takahashi H. Fall protection characteristics of safety belts and human impact tolerance. Ind Health 2014; 52 : 424–431.

Amiri M, Ardeshir A, Fazel Zarandi MH. Risk-based analysis of construction accidents in Iran during 2007-2011-meta analyze study. Iran J Public Health 2014; 43 : 507–522.

Das S. Occupational fatalities in the construction sector: a medico-legal viewpoint. Med Leg J 2015; 83 : 93–97.

Gurcanli GE, Mungen U. Analysis of construction accidents in turkey and responsible parties. Ind Health 2013; 51 : 581–595.

Hänecke K, Tiedemann S, Nachreiner F, Grzech-Sukalo H. Accident risk as a function of hour at work and time of day as determined from accident data and exposure models for the German working population. Scand J Work Environ Health 1998; Suppl 3 : 43–48.

Sadeghniiat-Haghighi K, Yazdi Z. Fatigue management in the workplace. Ind Psychiatry J 2015; 24 : 12–17.

Marucci-Wellman HR, Lombardi DA, Willetts JL. Working multiple jobs over a day or a week: short-term effects on sleep duration. Chronobiol Int 2016; 33 : 630–649.

Štítky

Patologie Soudní lékařství Toxikologie

Článek Miroslav Hirt sedmdesátiletý

Článek vyšel v časopiseSoudní lékařství

2020 Číslo 3-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Analysis of fatal industrial accidents in forensic postmortem investigations in South Osaka

- Sudden and unexpected death due to unilateral tonsillitis

- Fatal consequences of uterine rupture in late pregnancy

- Recodification of expert law in the Czech Republic since 2021 and its impact on expertise in health care with special regard to forensic medicine

- Miroslav Hirt sedmdesátiletý

- Soudní lékařství

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Fatal consequences of uterine rupture in late pregnancy

- Miroslav Hirt sedmdesátiletý

- Recodification of expert law in the Czech Republic since 2021 and its impact on expertise in health care with special regard to forensic medicine

- Sudden and unexpected death due to unilateral tonsillitis

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání