-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

proLékaře.cz / Odborné časopisy / Česká a slovenská neurologie a neurochirurgie / 2018 - Suplementum 1Chondroblastic osteosarcoma of maxilla, a patient with Li- Fraumeni syndrome

Chondroblastický osteosarkom maxily, pacientka s Li-Fraumeni syndromem

Osteosarkom čelistních kostí představuje velice vzácný a vysoce zhoubný novotvar, který může být jedním z projevů Li-Fraumeniho syndromu – dědičného onemocní, charakterizovaného vysokou pravděpodobností časného vzniku širokého spektra maligních nádorů. Incidence osteosarkomů čelistních kostí je asi 0,07/ 100 000. Prognózu pacienta nejvíce ovlivňuje stádium tumoru a možnost kompletního radikálního odstranění nádoru. Vzhledem k vzácnosti tohoto onemocnění bývají osteosarkomy čelistí zpočátku často špatně diagnostikované, což vede ke zpoždění v zahájení léčby a zhoršení prognózy. V tomto článku prezentujeme případ 32leté pacientky s Li-Fraumeni syndromem postižené chondroblastickým osteosarkomem, který také nebyl v úvodu správně diagnostikován. Po nekompletní resekci a časné lokální recidivě, která zcela vyplnila defekt po subtotální maxilektomii, bylo chemoradioterapií dosaženo kurativní odpovědi a více než 7letého přežití bez návratu onemocnění. Dále ve sdělení popisujeme příznaky, diagnostiku a léčbu tohoto vzácného onemocnění a také se zaměřujeme na Li-Fraumeniho syndrom. Zajímavostí tohoto případu je kurativní odpověď osteosarkomu po podání chemoradioterapie, která je všeobecně pokládaná jen za paliativní léčbu. Nečekaná odpověď některých nádorů na léčbu, stejně jako role mutace genu p53 stále nejsou zcela objasněny a jsou předmětem rozsáhlého výzkumu.

Klíčová slova:

chondroblastický osteosarkom – Li-Fraumeni syndrom – čelist

Autoři deklarují, že v souvislosti s předmětem studie nemají žádné komerční zájmy.

Redakční rada potvrzuje, že rukopis práce splnil ICMJE kritéria pro publikace zasílané do biomedicínských časopisů.

Authors: J. Zelinka; J. Blahák; Z. Daněk; O. Bulik

Authors place of work: Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic ; Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University Hospital Brno, Czech Republic

Published in the journal: Cesk Slov Neurol N 2018; 81(Suplementum 1): 47-50

Category: Původní práce

doi: https://doi.org/10.14735/amcsnn2018S47Summary

Osteosarcoma of the jaw is a very rare and highly malignant tumor, which could be a manifestation of Li-Fraumeni syndrome – an inherited cancer syndrome characterized by a high frequency and wide spectrum of early onset neoplasms. Incidence of jaw osteosarcoma is only about 0.07/ 100,000 per year. The tumor’s stage and possibility of complete surgical removal have the biggest impact on patient prognosis. Because rare, osteosarcomas are often misdiagnosed initially, which delays treatment and worsens the prognosis. We present a 32-year-old female patient with Li – Fraumeni syndrome and initially misdiagnosed chondroblastic osteosarcoma. After incomplete resection and early local recurrence, which completely filled the defect after subtotal maxillectomy, we achieved curative response and more than 7 years disease-free survival with chemo-radiotherapy. Furthermore, we describe symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of this rare disease, and also focus on Li – Fraumeni syndrome. Outcome of this case report disagrees with the widely held tenet that chemo-radiotherapy of osteosarcoma of the jaw is considered only a palliative treatment, unexpected response of some tumors to treatment, and the role of p53 mutations still are not clear and are the object of extensive investigations.

Key words:

chondroblastic osteosarcoma – Li-Fraumeni syndrome – jaw

Introduction

Osteosarcoma is highly malignant bone tumor in which mesenchymal cells produce osteoid. There are three histological sub-types of osteosarcomas – osteoblastic, chondroblastic and fibroblastic, depending on predominance of the neoplastic component. Although they are the secondmost common primary malignant bone tumor after multiple myeloma, they are still very rare [1]. Incidence of osteosarcomaof the jaw is about 0.07 case per 100,000 po-pulation per year [2]. Men develop osteosarcoma more often than women (about 60% of patients with jaw osteosarcoma are men) [1,2]. There are some differences between osteosarcomas of the jaw and those of the long bones, which are more common. The peak incidence for jaw osteosarcoma is in the 3rd–4th decade, while the average age of occurrence of conventional osteosarcoma is about decade earlier [1,2]. Also, in biological behavior osteosarcoma of jaws differs from conventional osteosarcomas by a lower incidence of metastasis and better prognosis, on the other hand the radical surgical treatment as well as radiotherapy of sarcomas of the bones of the face can change negatively and influence quality of life, due to function deficits and esthetic of the face, especially when healing complications after radiotherapy occur [1 – 4]. The etiology of osteosarcoma of the jaws is not known, it has been associated with radiotherapy, Paget disease, trauma, etc. Osteosarcomas are also characteristic for Li – Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), which is a rare, dominantly inherited cancer syndrome characterized by high frequency of early onset and a wide spectrum of neoplasms. Most common are sarcomas, premenopausal breast carcinomas, carcinomas of the lung, skin, pancreas and adrenal cortex, leukemia, and brain tumors [2,3,5 – 8]. Classic LFS was defined as proband, with sarcoma diagnosed under age 45 years, who has a first degree relative with any cancer under 45 years, and another first - or second-degree relative with either any cancer under 45 years or a sarcoma at any age [9].

Case report

A 32-year-old woman was referred to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University Hospital Brno, for gradually enlarging swelling on the right side of the hard palate. For about a month her dentist treated the condition as odontogenic infection, by extraction of the second right upper molar, which was not vital. She also complained about pressure in the right maxilla. Intraoral examination demonstrated an extraction socket without any pathology, and painless, firm swelling of the right hard palate. Patient history reveled a high risk for malignant disease caused by the presence of LFS and p53 mutation in patient’s family. The patient in the past underwent genetic testing and she is a p53 germ-line mutation carrier. The patient had not informed her dentist about this condition. Panoramic radiography and Water’s view of skull revealed a radiopaque mass in the right maxillary sinus. An incisional biopsy was performed, but microscopic examination showed only chronic inflammatory infiltration.

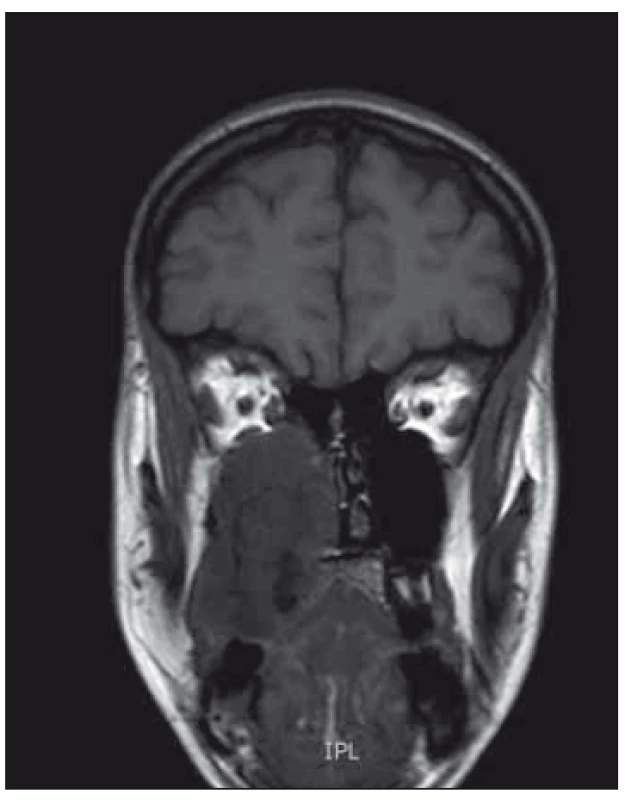

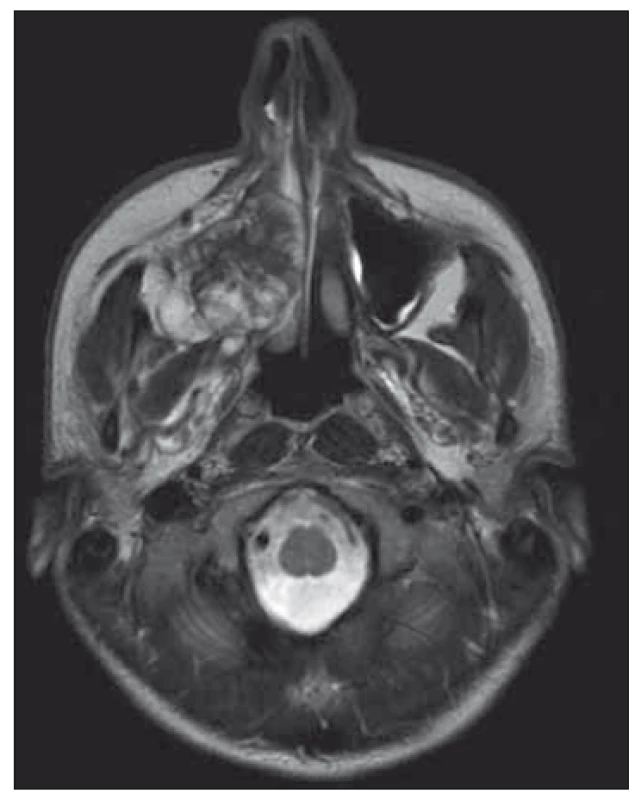

Continuing suspicion of a malignant lesion led us to further investigation. Another incisional biopsy and head CT scan were performed. Histopathological examination of the second specimen established the final diagnosis of high grade (G3) chondroblastic osteosarcoma with TP53 mutation in 100% of the tumor cells. The CT image showed a lesion inside the right maxillary sinus extending to the nasal cavity, ethmoidal cells, and pterygopalatine fossa. For better anatomic definition, a head MRI was performed (Fig. 1, 2). Bone scintigraphy, chest CT scan, and ultrasonography of neck, abdomen, and pelvis showed no metastatic spread of osteosarcoma. During 2 weeks there was visible local progression of the disease; tumorous spread to the vestibule, and also onto the alveolar ridge. Patient started to complain about nasal obstruction. Patient underwent subtotal maxillectomy, but the tumor was too large and not amenable to complete surgical intervention, mainly in the pterygopalatine fossa. Local recurrence began soon after surgery and the tumor mass completely filled the defect after previous operation. The oncologists decided to use palliative chemotherapy and radiotherapy. After four cycles of chemotherapy (doxorubicin, cisplatina) (the 3rd and 4th cycles of chemotherapy were reduced 25% for poor tolerance and toxicity), and locoregional radiotherapy 57.2 Gy (26 × 2.2 Gy), complete remission of the disease was achieved. Almost 7 years after adjuvant therapy, the patient was without recurrence of the tumor. The defect after subtotal maxillectomy was covered with an obturator prosthesis, with good function and esthetic, no impaired wound healing after chemotherapy and radiotherapy had occurred and good quality of life was achieved.

Fig. 1. MRI coronar view – demonstrates large mass in the maxilla extending to the nasal cavity, also causing bulging and destruction of hard palate.

Obr. 1. MR koronární pohled – zobrazuje masivní hmotu v horní čelisti až do nosní dutiny, což také způsobuje deviaci a destrukci tvrdého patra.

Fig. 2. MRI transverse view – sarcoma in the right maxilla, obstructing right part of nose, deviating nasal septum and expanding into infratemporal fossa.

Obr. 2. MR příčný/transverzální pohled – sarkom v pravé maxile, obstrukce pravé části nosu, odklonění nosní přepážky a rozšíření do infratemporální fossy.

Discussion

Osteosarcoma is a highly malignant, but rare, tumor. Its incidence is about 1 case per 100,000 persons, with approximately 4% to 8% arising in the jaw. As a result, with few case reports or retrospective studies available, diagnosis, mainly in the early stages, is made more difficult [2,3,10,11]. In August’s review of 30 osteosarcomas of the jaw 13 were initially misdiagnosed as odontogenic infection, as in the case presented here [3]. Differential diagnosis of chondroblastic osteosarcoma, besides inflammation, includes fibrous dysplasia, Paget’s disease, high-grade carcinoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, and chondrosarcoma, which has similar histological features but better prognosis and lower potential for metastasis than chondroblastic osteosarcoma [12 – 14].

Symptoms of osteosarcomas of the jaws are not specific. Most patients complain of a mass or swelling, about half of the patients suffer pain; other symptoms are loose teeth or displacement of teeth, paresthesia, toothache, bleeding, and nasal obstruction. Radiological appearance may be a radiolucent, radiopaque, or mixed. In a study of 46 patients with craniofacial osteosarcomas the dominant pattern in mandibular tumors was osteoblastic, while in other craniofacial areas it was osteolytic. Plain films are of limited worth, while CT provides perfect anatomic definition of the tumor, and MRI is even more effective [15]. Histological evaluation of the biopsy specimen is always necessary to confirm diagnosis. Also, in the case presented the patient’s report of hard palate swelling was initially misdiagnosed as inflammation. The patient was later discovered to have LFS and is a p53 germ-line mutation carrier. This syndrome is characterized by a high frequency of early onset of various tumors. It is a rare condition, with mutations of p53 identified in 60% to 80% of families with LFS [16,17]. Wu et al. report that men with germ-line p53 mutation have 151-fold higher odds of developing cancer than those with no mutations; women have even higher odds – 1.075-fold. Lifetime risk of cancer was estimated at about 70% in males, and nearly 100% in females in LFS families [18,19].

There is still ethical controversy about genetic testing of possible p53 mutation carriers, especially in children. The patient in this case is the mother of two children, 6 and 11 years old, who have not been tested yet. The data show the importance of screening and follow up of individuals with LFS; nevertheless, no international consensus on clinical surveillance recommendations has been established. There are varying strategies in different countries. For example in the United States the National Comprehensive Cancer Network published the following guidelines: monthly breast self-exam starting at age 18; clinical breast exam every 6 months starting at age 20 – 25 or 5 – 10 years before the earliest known breast cancer in the family; annual mammogram or breast MRI starting at age 20 – 25; discuss option of risk-reducing mastectomy; annual physical exam, especially focused on skin and neurological assessment; colonoscopy every 2 – 5 years; additional organ-targeted surveillance based on family history [20]. The goal of screening is early establishment of a correct diagnosis, and curative treatment of tumors.

One difficulty with disease surveillance in LFS patients is that the spectrum of tumors is very wide and may be found in almost every site of the body. So, every doctor taking care of a patient with LFS, including the dentist, should be aware of the high risk of malignant disease to avoid delayed tumor recognition. For osteosarcomas of the jaw that are too large for radical resection the prognosis is very poor. In Clark’s review of 66 patients the recurrence rate for large tumors was 80% within 24 months, and with recurrence, the chances for survival were greatly decreased [1].

The presented case is interesting for several reasons, some of them are in disagreement with widely held tenets. First, chemotherapy and radiotherapy alone are generally considered to be palliative, with mortality estimated to be 100% [3]. In this case, early local recurrence completely filled the postoperative defect before any adjuvant therapy was set, but after chemo-radiotherapy complete remission was achieved, with no evidence of recurrence after almost 7 years. Second, the basis of tumor response to cancer treatment is still poorly understood; according to some studies tumor cells with mutations in p53 resist apoptosis, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy [21 – 27]. The response to chemotherapy and radiotherapy in the presented case was unexpected, with a curative outcome despite the patient being a p53 germ-line mutation carrier. Third, there is controversy about radiotherapy in patients with LFS. p53 germ-line mutation carriers have abnormal sensitivity to radiogenic carcinogenesis, and there is evidence that radiation-induced tumors frequently occur in the radiation field, radiotherapy also carries a risk of osteoradionecrosis of the jaw, xerostomia, radiation dermatitis, delayed wound healing and so on. So, it is believed that, if possible, radiotherapy should be avoided [6,28]. In this case, after very early local relapse, with very poor long-term prognosis, and knowledge that radiation-induced tumors occurred with latency often longer than 10 years, the oncologists decided to use a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy to achieve the best possible control of local spread.

After almost 7 years, patient is without any clinical or radiological sign of recurrence. Careful long-term follow-up of patients with LSF is crucial. Individuals with the p53 mutation are also at very high risk of developing secondary tumors, and radiation-induced sarcoma as a late sequel of radiation therapy. The goal of this article was to present and describe a rare tumor and syndrome with an unexpected curative response to palliative treatment.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

Jiří Zelinka, MD

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery University Hospital Brno

Jihlavská 20

625 00 Brno

Czech Republic

e-mail: zelinka.jiri@email.cz

Accepted for review: 13. 7. 2018

Accepted for print: 16. 8. 2018

Zdroje

1. Clark JL, Unni KK, Dahlin DC et al. Osteosarcoma of the jaw. Cancer 1983; 51(12): 2311 – 2316.

2. Garrington GE, Scofield HH, Cornyn J et al. Osteosarcoma of the jaws. Analysis of 56 cases. Cancer 1967; 20(3): 377 – 391.

3. August M, Magennis P, Dewitt D. Osteogenic sarcoma of the jaws: factors influencing prognosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997; 26(3): 198 – 204.

4. Chindia ML. Osteosarcoma of the jaw bones. Oral Oncol 2001; 37(7): 545 – 547.

5. Chabchoub I, Gharbi O, Remadi S et al. Postirradiation osteosarcoma of the maxilla: a case report and current review of literature. J Oncol Internet 2009 : 876138. doi: 10.1155/ 2009/ 876138.

6. Chompret A. The Li – Fraumeni syndrome. Biochimie 2002; 84(1): 75 – 82.

7. Varley JM, Evans DG, Birch JM. Li-Fraumeni syndrome – a molecular and clinical review. Br J Cancer 1997; 76(1): 1 – 14.

8. Li FP, Fraumeni J, Joseph F. Soft-tissue sarcomas, breast cancer, and other neoplasms. A familial syndrome? Ann Intern Med 1969; 71(4): 747 – 752.

9. Li FP, Fraumeni JF, Mulvihill JJ et al. A cancer family syndrome in twenty-four kindreds. Cancer Res 1988; 48(18): 5358 – 5362.

10. Cade S. Malignant disease and its treatment by radium. London: Simpkin Marshall 1952.

11. George A, Mani V, Sunil S et al. Osteosarcoma of maxilla – a case of missed initial diagnosis. Oral Maxillofac Pathol J 2010; 1 : 1–7.

12. Gupta N, Rajwanshi A, Gupta P et al. Chondroblastic osteosarcoma of the temporal region: a diagnostic dilemma. Diagn Cytopathol 2011; 39(5): 377 – 379. doi: 10.1002/ dc.21440.

13. Saito K, Unni KK, Wollan PC et al. Chondrosarcoma of the jaw and facial bones. Cancer 1995; 76(9): 1550 – 1558.

14. Amaral MB, Buchholz I, Freire-Maia B et al. Advanced osteosarcoma of the maxilla: a case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cirugia Bucal 2008; 13(8): E492 – E495.

15. Lee Y, Van Tassel P, Nauert C et al. Craniofacial osteosarcomas: plain film, CT, and MR findings in 46 cases. Am J Roentgenol 1988; 150(6): 1397 – 1402. doi: 10.2214/ ajr.150.6.1397.

16. Kleihues P, Schauble B, zur Hausen A et al. Tumors associated with p53 germline mutations: a synopsis of 91 families. Am J Pathol 1997; 150(1): 1 – 13.

17. Olivier M, Goldgar DE, Sodha N et al. Li-Fraumeni and related syndromes: correlation between tumor type, family structure, and TP53 genotype. Cancer Res 2003; 63(20): 6643 – 6650.

18. Malkin D. Li-Fraumeni Syndrome. Genes Cancer 2011; 2(4): 475 – 484. doi: 10.1177/ 1947601911413466.

19. Wu CC, Shete S, Amos CI et al. Joint effects of germ-line p53 mutation and sex on cancer risk in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cancer Res 2006; 66(16): 8287 – 8292. doi: 10.1158/ 0008-5472.CAN-05-4247.

20. Mai PL, Malkin D, Garber JE et al. Li-Fraumeni syndrome: report of a clinical research workshop and creation of a research consortium. Cancer Genet 2012; 205(10): 479 – 487. doi: 10.1016/ j.cancergen.2012.06.008.

21. Bergamaschi D, Gasco M, Hiller L et al. p53 polymorphism influences response in cancer chemotherapy via modulation of p73-dependent apoptosis. Cancer Cell 2003; 3(4): 387 – 402.

22. McIlwrath AJ, Vasey PA, Ross GM et al. Cell cycle arrests and radiosensitivity of human tumor cell lines: dependence on wild-type p53 for radiosensitivity. Cancer Res 1994; 54(14): 3718 – 3722.

23. Weller M. Predicting response to cancer chemotherapy: the role of p53. Cell Tissue Res 1998; 292(3): 435 – 445.

24. Huang HY, Illei PB, Zhao Z et al. Ewing sarcomas withp53 mutation or p16/ p14ARF homozygous deletion: a highlylethal subset associated with poor chemoresponse. J ClinOncol 2005; 23(3): 548 – 558. doi: 10.1200/ JCO.2005.02.081.

25. Brown JM, Wouters BG. Apoptosis, p53, and tumor cell sensitivity to anticancer agents. Cancer Res 1999; 59(7): 1391 – 1399.

26. Wunder JS, Gokgoz N, Parkes R et al. TP53 mutations and outcome in osteosarcoma: a prospective, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23(7): 1483 – 1490. doi: 10.1200/ JCO.2005.04.074.

27. Keshelava N, Zuo JJ, Chen P et al. Loss of p53 function confers high-level multidrug resistance in neuroblastoma cell lines. Cancer Res 2001; 61(16): 6185 – 6193.

28. Limacher JM, Frebourg T, Natarajan-Ame S et al. Two metachronous tumors in the radiotherapy fields of a patient with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Int J Cancer 2001; 96(4): 238 – 242.

Štítky

Dětská neurologie Neurochirurgie Neurologie

Článek vyšel v časopiseČeská a slovenská neurologie a neurochirurgie

Nejčtenější tento týden

2018 Číslo Suplementum 1- Metamizol jako analgetikum první volby: kdy, pro koho, jak a proč?

- Magnosolv a jeho využití v neurologii

- Zolpidem může mít širší spektrum účinků, než jsme se doposud domnívali, a mnohdy i překvapivé

- Moje zkušenosti s Magnosolvem podávaným pacientům jako profylaxe migrény a u pacientů s diagnostikovanou spazmofilní tetanií i při normomagnezémii - MUDr. Dana Pecharová, neurolog

- Nejčastější nežádoucí účinky venlafaxinu během terapie odeznívají

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- The factors of pressure ulcer’s healing in critically ill patients

- The pressure ulcers in patients with comorbid neurological disorders

- Factors influencing recurrence of the pressureulcers after plastic surgery – retrospective analysis

- Wound healing effects after application of polyunsaturated fatty acids in rat

- Pressure injuries prevention is better than solving of their complications

- Pressure ulcers in outpatients of the Spinal Unit of University Hospital Brno 2013– 2016

- Supraclavicular flap in reconstruction of intraoral defects

- Chondroblastic osteosarcoma of maxilla, a patient with Li- Fraumeni syndrome

- Pressure lesion monitoring – data set validation after second pilot data collection

- Česká a slovenská neurologie a neurochirurgie

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- The pressure ulcers in patients with comorbid neurological disorders

- Chondroblastic osteosarcoma of maxilla, a patient with Li- Fraumeni syndrome

- Supraclavicular flap in reconstruction of intraoral defects

- Pressure lesion monitoring – data set validation after second pilot data collection

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání