-

Medical journals

- Career

Perigraft seroma as a rare angiosurgical complication

Authors: A. Gazi 1; R. Staffa 1,3; T. Novotný 1,3; Z. Kriz 1; M. Hermanová 2,3

Authors‘ workplace: nd Department of Surgery, Center for vascular disease, St. Anne’s University Hospital, Brno The Head of Department: prof. MUDr. R. Staffa, Ph. D. 1; 1st Institute of Pathological Anatomy, St. Anne’s University Hospital, Brno The Head of the Department: prof. MUDr. M. Hermanová, Ph. D. 2; Medical Faculty, Masaryk University, Brno The Dean of the Faculty: prof. MUDr. J. Mayer, CSc. 3

Published in: Rozhl. Chir., 2015, roč. 94, č. 11, s. 477-481.

Category: Case Report

Overview

Perigraft seroma is quite a rare complication that may occur after implantation of Dacron or expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) vascular grafts. We report a case of a 54-year-old patient with perigraft seroma around an axillofemoral bypass (ePTFE graft). Definitive treatment involved the explantation of this extraanatomic bypass with perigraft seroma and the implantation of an aortobiiliac bypass using vascular prosthesis made of a different material. Based on published studies, therapeutic options for this complication are discussed. No guidelines or recommendations are available. In conclusion, the approach to perigraft seroma treatment remains strictly individual. Vascular graft replacement using grafts made of different material seems to be the best option in the case of recurring perigraft seroma, where less invasive procedures were not successful.

Key words:

perigraft seroma − Dacron – ePTFE − vascular graft – extra-anatomic bypassIntroduction

Perigraft seroma (PS) is quite a rare complication that occurs after implantation of Dacron or expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) vascular grafts. It may develop around vascular prostheses when placed in a subcutaneous location [1]. However, according to a recently published retrospective study, a significant risk of PS occurrence and possible complications was also shown after vascular graft placement in the aortoiliac region [2]. Other locations of possible PS occurrence are prosthetic arteriovenous shunts, where PS are prone to develop in the area of arterial anastomosis [3]. The total incidence of PS around ePTFE grafts at all locations is around 0.48% regardless of the anatomical placement of the grafts [4]. The risk of PS is higher in extra-anatomic reconstructions, reaching 4.2% of cases [5]. After open resection of an abdominal aortic aneurysm and reconstruction by ePTFE aortobiiliac prosthesis, the occurrence of PS within the original aneurysm sac is described in 2.3% of cases [6]. It is apparent that many perigraft seromas do not clinically manifest, and they heal spontaneously.

The onset of symptoms is common from the first month after operation up to several years thereafter. It manifests as the development of a clear sterile perigraft serous collection surrounded by a fibrous nonsecretory pseudocapsule [7]. The patient is without clinical signs of acute or chronic inflammation, and inflammatory markers are normal. PS grows gradually. Initially it is not painful. Later, because of its volume, it causes compressive syndrome with the compression of surrounding tissues, thinning of skin layers, emergence of pain, and increased risk of infection. The consistency of seroma is liquid or gelatinous.

We report a case of a 54-year-old patient with perigraft seroma around an axillofemoral bypass (ePTFE vascular graft).

Case Report

The subject of our case study is a 54-year-old patient previously diagnosed with peripheral artery disease (stage 1 - Rutherford classification), arterial hypertension, coronary heart disease, history of myocardial infarction after PCI with stent implantation, chronic heart failure (stage III - NYHA classification) and nicotinism.

He was urgently admitted to a coronary care unit because of a 4-week history of gradually progressing atypical stenocardia with irradiation to the cervical area. During the past 24 hours before admission to the coronary care unit a progression of problems occurred with vomiting and short loss of consciousness, with the onset of rest pain in the lower abdomen, groins, and both lower extremities.

The patient stated that about 14 days before admission the claudication interval shortened to less than 200 meters, expressed more intensely in the left lower extremity with intermittent mild rest pain and paraesthesia. After admission, a CT angiography showed thrombosis of the abdominal aortic bifurcation and the orifices of both common iliac arteries. Findings showed positive cardiac markers, hypokalaemia, myoglobinaemia, and leukocytosis. The patient was diagnosed as having subacute myocardial infarction of the anterior wall and thrombosis of aortic bifurcation with bilateral occlusion of the common iliac arteries.

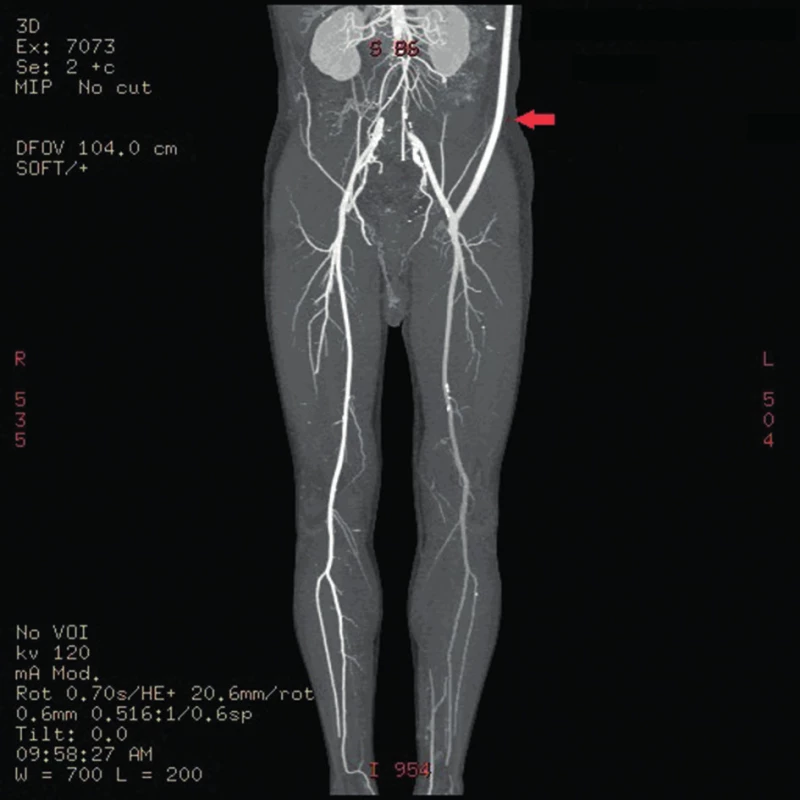

The patient was discussed at the Vascular Multidisciplinary Team Meeting and an open surgical revascularisation was indicated, because the arterial lesion at the level of aortic bifurcation was unsuitable for thrombectomy or endovascular intervention. It was not possible to implant an aortobiiliac bypass at that time because of the overall condition of the patient (ejection fraction 28%, Troponin-T 0.7 µg/l, ASA IV (The American Society of Anesthesiologists), sinus rhythm). We could perform only a less extensive surgical procedure in the form of axillofemoral bypass on the clinically worse left lower extremity (Fig. 1). A cardiologist considered the patient’s state to be stable for undergoing urgent revascularisation of the left lower extremity. However, the patient refused the proposed surgery and later signed a negative consent. After two months, the patient was readmitted for clinical signs of acute ischemia of the left lower extremity presenting with intense rest pain and loss of movement and sensation of the left lower leg. The patient was educated on the expected outcomes of the treatment and informed consent was obtained prior to surgery using standard protocols of the department. Urgent surgery was performed in the form of direct thrombectomy of the left deep femoral artery and implantation of a left-sided axillofemoral bypass. The ringed vascular prosthesis VascuGraft PTFE (B. Braun Melsungen AG) was used. The surgery had a good effect on the blood flow of the afflicted limb, and postoperatively there was a palpable pulsation on the left dorsalis pedis artery and the left posterior tibial artery.

1. CT angiography showing functional left-sided axillofemoral bypass (arrow)

Approximately seven weeks after the procedure, subcutaneous fluctuations of the size of a man´s fist started to develop in the left subclavian area and left groin. The axillofemoral bypass was patent (Fig. 2,3).

2. Perigraft seroma around left-sided axillofemoral bypass (standing position)

3. Perigraft seroma around left-sided axillofemoral bypass (lying position)

In the subsequent period, the patient was readmitted to hospital three times for relapse of fluctuation in the left groin and under the left clavicle. Blood tests showed the levels of CRP to be constantly under 15mg/l, without evidence of leukocytosis. Fluid surrounding the graft was cytologically and microbiologically examined. The result of the examination was consistent with transudate origin of the fluid. In an oligocellular sample, the presence of dominating lymphoid elements was confirmed, with the admixture of plasmocytes, eosinophils, erythrocytes, and histocytes. All aspirate samples were microbial culture negative. Because of repeated relapses of seroma surrounding the graft, with persistent discomfort of the patient, we considered explantation of the axillofemoral bypass with extirpation of perigraft pseudocapsules and implantation of an aortobiiliac bypass. This surgical procedure was already feasible at that time because of the general stabilisation and improvement of internal conditions of the patient, enabling a more complex angiosurgical procedure to be done (ejection fraction 35%, Troponin-T negative, ASA III, sinus rhythm).

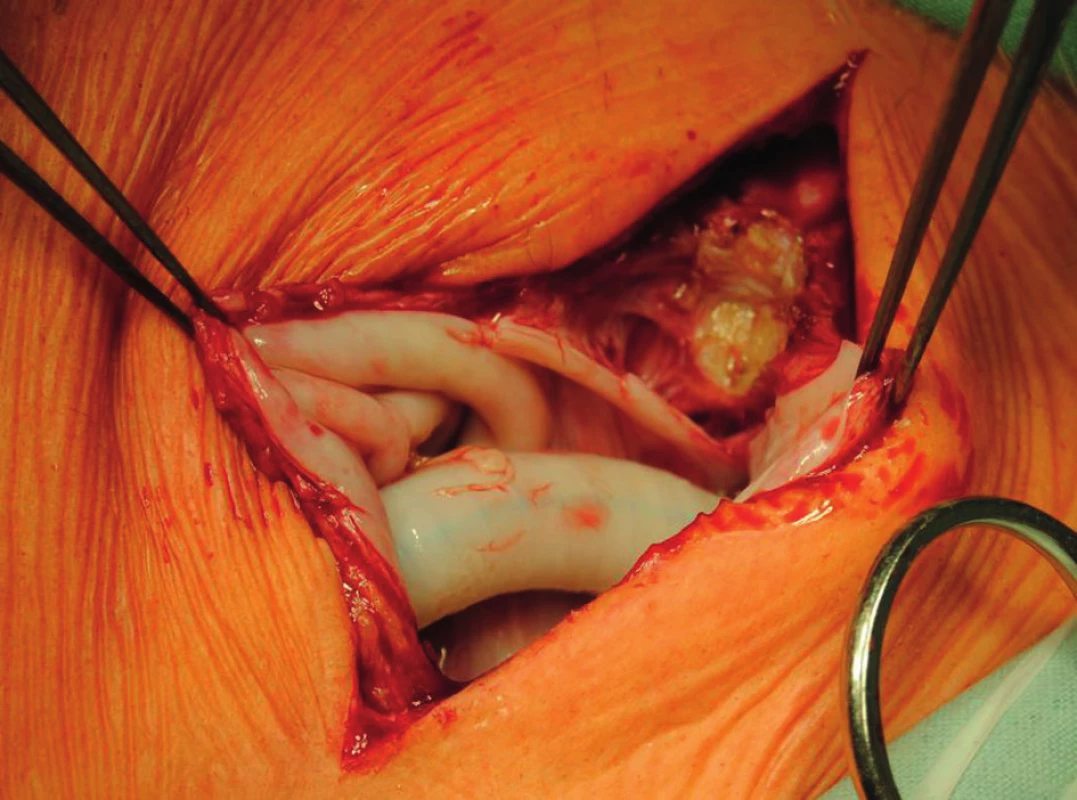

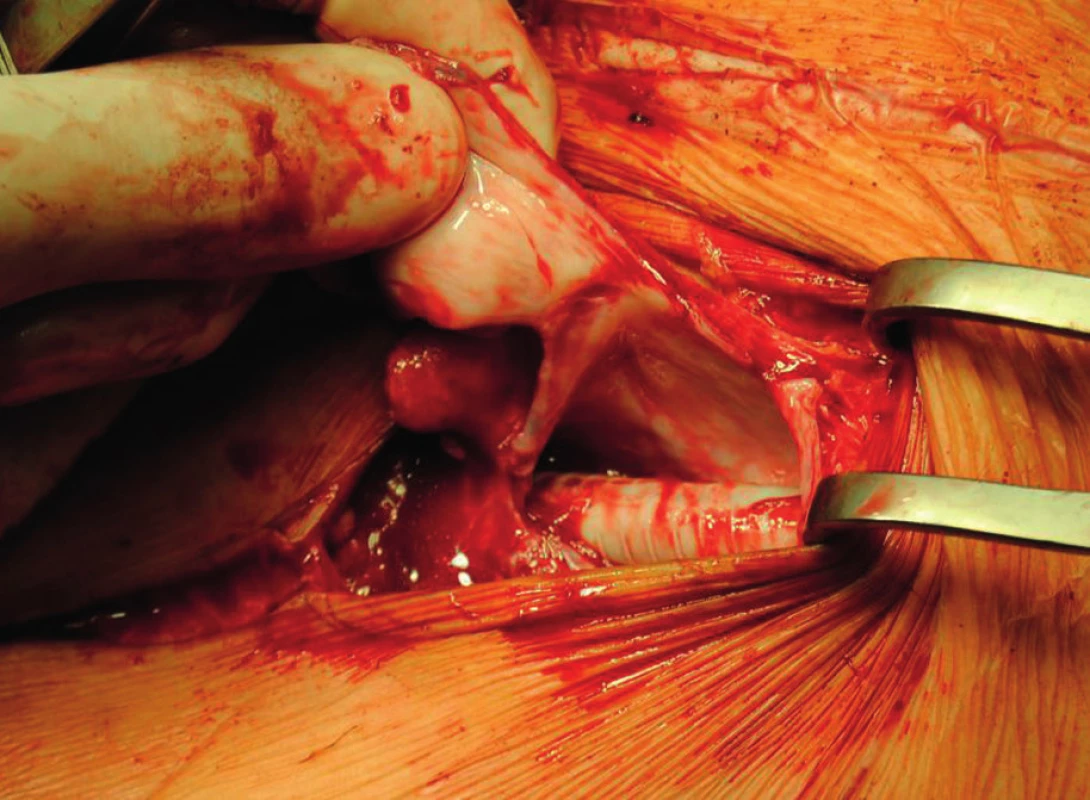

A two-phased elective procedure was performed. First, a thrombectomy of the subrenal abdominal aorta and the implantation of the aortobiiliac bypass (on the right to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery, on the left to the external iliac artery) using Dacron graft were performed. To lower the risk of PS relapse, we chose a different type of prosthesis. Second, during the same surgery, we explanted the left-sided axillofemoral bypass with extirpation of most of the pseudocapsules in the distal part of the original tunnel. In the left groin, after bypass explantation, we closed the defect using a venous patch from the great saphenous vein. In the left subclavian area, because of problematic surgical access, a ligated stump of the original ePTFE graft was left (Fig. 4−6).

4. Proximal anastomosis of axillofemoral bypass before its explantation. A white pseudocapsule is present around the graft.

5. Distal anastomosis of the axillofemoral bypass before its explantation with visible pseudocapsule

6. Ligated graft stump left after explantation of the ePTFE graft in the area of proximal anastomosis of the axillofemoral bypass

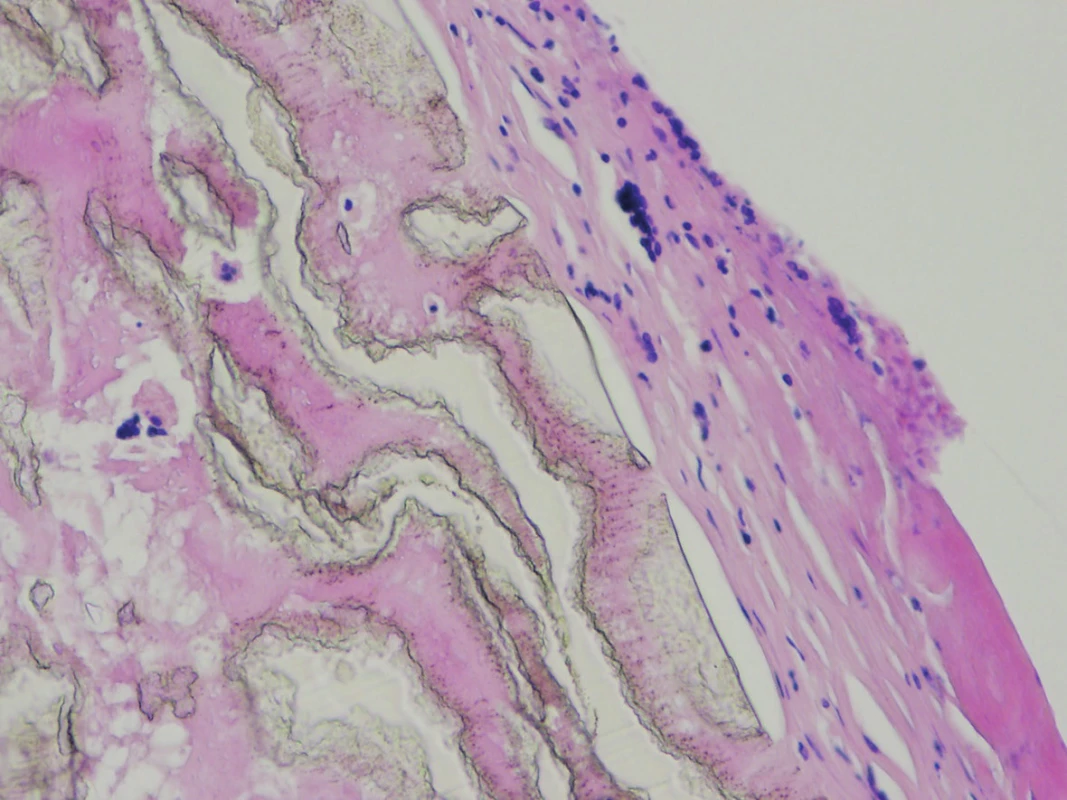

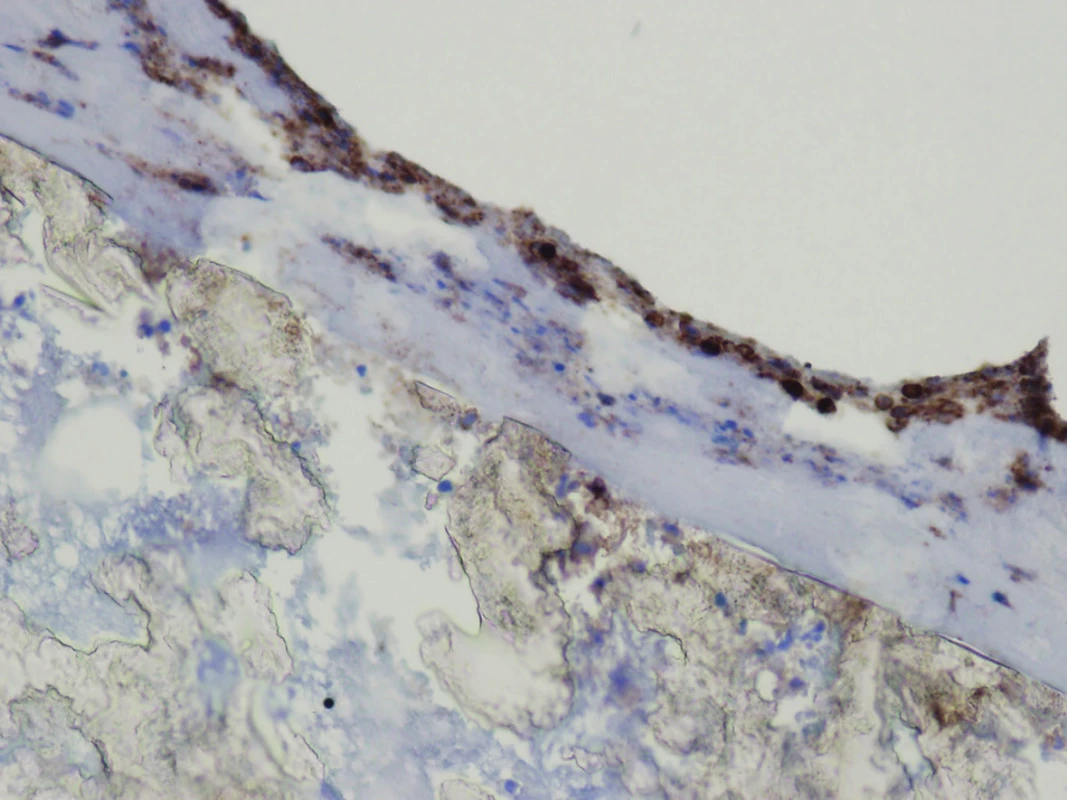

The explanted vascular prosthesis was histologically examined after processing using formol-paraffin technique. In a hematoxylin-eosin and van Gieson staining, a focal lympho-plasmocytic inflammatory infiltration of an outer fibrous pseudomembrane was displayed (Fig. 7). The presence of cells of lympho-plasmocytic infiltration was also verified by immunohistochemical proof of expression of leukocyte common antigen (LCA, Fig. 8). The results of the examination of expression of B (CD20) and T (CD3) markers were inconclusive. Samples of the explanted vascular graft from three different locations were sent for sonicated microbial cultures and genetic examination to exclude graft infection. Results were negative in all samples.

7. The surface of the vascular graft, fibrous membrane infiltrated by lympho-plasmocytic inflammatory infiltration

(Hematoxylin-eosin, magnification: 200x.) 8. Immunohistochemical proof of expression of leukocyte common antigen (LCA) in the cells of lympho-plasmocytic inflammatory infiltration in fibrous pseudomembrane on the surface of the graft

(Immunohistochemistry LCA, magnification: 200x.) In subsequent follow-up after 12 months from the operation, the patient did not observe any relapse of PS, he negated claudication on both extremities, and he had palpable pulsations on both dorsalis pedis arteries. Ultrasound examination did not confirm free fluid in the abdominal cavity, either in the retroperitoneum, around the Dacron graft, or in the area of extirpated pseudocapsules.

Discussion

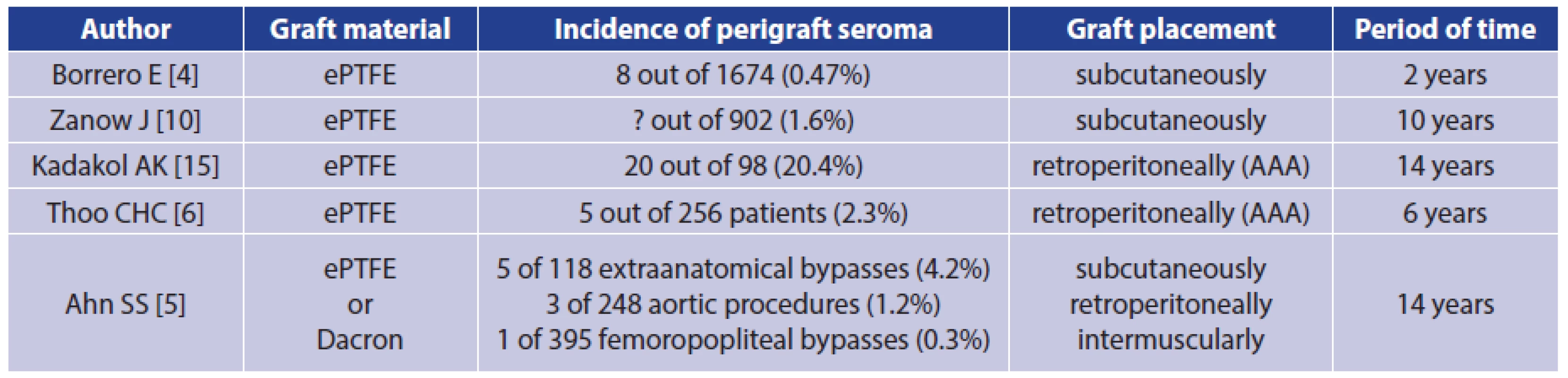

Perigraft seroma is quite a rare complication of vascular reconstructive operations in which Dacron or PTFE grafts are used (Tab. 1). In many cases, it does not present clinically at all. On the other hand, depending on the location, it can cause patients considerable discomfort and expose them to constant risk of infection of seroma and thus infection of the vascular graft.

1. Incidence of perigraft seroma around Dacron and ePTFE grafts in selected studies

? = number not mentioned in the full text of the article The development of PS is related to the failure of the graft to become incorporated into the surrounding tissue and to increased ultrafiltration of plasma-like liquid through the wall of vascular prosthesis [5,7]. The maximum of such ultrafiltration is in the place of the pressure gradient, which is most frequently in the area of arterial anastomosis. The aetiology of increased graft permeability is still unclear [8]. Histopathologically, it resembles a reactive fibroplastic proliferation, which is a form of aseptic inflammation with a proliferation of fibroblasts in a fibrous pseudomembrane on the surface of the vascular graft with the possible presence of a lympho-plasmocytic inflammatory infiltration. In all cases, the graft is only poorly incorporated into the surrounding tissues [7].

Dealing with this angiosurgical complication is not ruled by any guidelines, and it is more or less individual with regard to the overall condition of the patient. In significantly compromised patients, the less invasive approach is more likely to be chosen. According to the literature data in a group of 279 patients, the highest success rate was noted with a replacement of the vascular graft, in 92% of cases. Simply observation or seroma aspiration had almost the same success rate, 68% and 69% respectively, although aspiration was complicated by the infection or thrombosis of the vascular graft in 8%. Moreover, pseudocapsule removal was successful in 72% of cases. However, the incidence of infection or thrombosis with this approach was up to 12%. Based on the mentioned study, in a case that involved increasing and large seromas, the author recommended a resection of only the affected segment of the original graft and its replacement with an alternative type of a new vascular graft, ideally routed through a newly created tunnel [9].

Other studies describe methods with fibrin sealing of the outer surface of the graft [10], wrapping the graft with an autologous great saphenous vein [11], and percutaneous implantation of a Dacron stent graft for closed inner drainage [12]. All the stated methods were used in a small number of patients and require more thorough study.

In our case the perigraft seroma occurred in the surroundings of an extra-anatomic axillofemoral bypass in a patient, in whom this bypass had been implanted urgently as the only option of saving the acutely ischemic left limb, under overall compromised internal conditions of the patient. After the occurrence of seroma, we first adopted a conservative approach, later with repeated punctures of the seroma cavity. However, this treatment was not successful. Moreover, the patient was repeatedly exposed to the risk of graft infection. During this period, all microbiological cultures of aspirate samples were negative and no clinical or laboratory findings were suggestive of graft infection. Another promising method for vascular graft infection diagnosis seems to be 18F-FDG PET/CT [13], however its sensitivity and specificity is still being questioned and no standards of evaluation of its results have been agreed upon [14]. We did not use this diagnostic tool in the reported case.

The patient’s overall condition was improved at that time and allowed a more extensive procedure. We indicated explantation of the axillofemoral bypass and implantation of the aortobiiliac bypass at the same time. This method might be beneficial for the patient not only because it treated relapsing PS, but also because, in general, an aortobiiliac bypass has better long-term patency than an axillofemoral bypass. We could not exclude the possibility that the cause of PS was in reaction to an artificial material, so we chose a different type of material for the graft in the aortoiliac location. On follow-up ultrasound examination, no signs of relapse of seroma around the graft, in the retroperitoneum, or in the area of the original extra-anatomic bypass were found. The condition of the patient was resolved without further complications.

Conclusions

The approach to perigraft seroma treatment is strictly individual, which is also supported by literature data. Vascular graft replacement using prosthesis made of different material seems to be the best option in the case of recurring perigraft seroma, where less invasive procedures were not successful.

This work was supported by a grant from the Czech Health Research Council (Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic) ‘‘Education Influence on the Selected Psychosomatic Factors in Patients Indicated for the Vascular Prosthesis Implantation’’ No. 15-33437A.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have not conflict of interest in connection with the emergence of and that the article was not published in any other journal.

MUDr. Tomáš Novotný, Ph.D.

II. chirurgická klinika LF MU a FN u sv. Anny, Pekařská 53

656 91 Brno

e-mail: tomas.novotny@fnusa.cz

Sources

1. Cannon J, Bolton W. Seroma formation associated with PTFE vascular grafts used as arteriovenous fistulae. Dial Transpl 1981;10 : 60−8.

2. Wolff T, Koller MT, Eugster T, et al. Endarterectomy of the aneurysm sac in open ab dominal aortic aneurysm repair reduces perigraft seroma and improves graft incorporation. World J Surg 2011;35 : 905–10.

3. Schanzer H. Overview of complications and management after vascular access creation. In: Gray RJ, ed. Dialysis Access. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2002 : 93−7.

4. Borrero E, Doscher W. Chronic perigraft seromas in PTFE grafts. J Cardiovasc Surg 1988;29 : 46–9.

5. Ahn SS, Machleder HI, Gupta R, et al. Perigraft seroma: Clinical, histologic, and serologic correlates. Am J Surg 1987;154 : 173–8.

6. Thoo CHC, Bourke BM, May J. Symptomatic sac enlargement and rupture due to seroma after open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair with polytetrafluoroethylene graft: Implications for endovascular repair and endotension. J Vasc Surg 2004;40 : 1089–94.

7. Blumenberg RM, Gelfand ML, Dale WA. Perigraft seromas complicating arterial grafts. Surgery 1985;97 : 194–204.

8. Thevendran G, Lord R, Sarraf KM. Serous leak, a rare complication of polytetrafluoroethylene grafts: a case report. Cases J 2009;2 : 195.

9. Blumenberg RM. Invited commentary in lymph fistulas and seromas. In: Dale WA, ed. Management of vascular surgical problems. New York, McGraw-Hill 1985 : 293–8.

10. Zanow J, Kruger U, Settmacher U, et al. Treatment of perigraft seroma in expanded polytetrafluoroethylene grafts by sequential fibrin sealing of the outer graft surface. Ann Vasc Surg 2010;24 : 1005–14.

11. Imren Y, Qaradaghi L, Oktar GL, et al. Saphenous vein wrapping for the treatment of a perigraft seroma: Report of a case. Surg Today 2011;41 : 549–51.

12. Gargiulo NJ 3rd, Veith FJ, Scher LA, et al. Experience with covered stents for the management of hemodialysis polytetrafluoroethylene graft seromas. J Vasc Surg 2008;48 : 216–7.

13. Spacek M, Belohlavek O, Votrubova J, et al. Diagnostics of „non-acute“ vascular prosthesis infection using 18F-FDG PET/CT: Our experience with 96 prostheses. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2009;36 : 850−8.

14. Berger P, Vaartjes I, Scholtens A, et al. Differential FDG-PET uptake patterns in uninfected and infected central prosthetic vascular grafts. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2015;50 : 376−83.

15. Kadakol AK, Nypaver TJ, Lin JC, et al. Frequency, risk factors, and management of perigraft seroma after open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2011;54 : 637–43.

Labels

Surgery Orthopaedics Trauma surgery

Article was published inPerspectives in Surgery

2015 Issue 11-

All articles in this issue

- Hepatic pseudolesions adjacent to the falciform ligament

- Management of groin wound infection after arterial surgery using negative-pressure wound therapy

- Our experience with the measurement of transcutaneous oxygen tension for evaluation of blood circulation in peripheral arteries in patients with critical ischemic disease of lower limbs

- Determination of CEA, EGFR and hTERT expression in peritoneal lavage in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma using RT – PCR method

- Surgical therapy of pancreatic cancer – 5 years survival

- Vascular dialysis access with transposed superficial femoral vein

- Perigraft seroma as a rare angiosurgical complication

- Perspectives in Surgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Hepatic pseudolesions adjacent to the falciform ligament

- Our experience with the measurement of transcutaneous oxygen tension for evaluation of blood circulation in peripheral arteries in patients with critical ischemic disease of lower limbs

- Surgical therapy of pancreatic cancer – 5 years survival

- Management of groin wound infection after arterial surgery using negative-pressure wound therapy

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career