-

Medical journals

- Career

Gender Differences in Clinical Presentation and Occurence of Sleep Disturbances in Patiens with Parkinson’s Disease – a Population ‑ based Study

Authors: F. Cibulčík; A. Hergottová; K. Kračunová; J. Benetin

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Neurology, Slovak Medical University and University Hospital Bratislava, Slovak Republic

Published in: Cesk Slov Neurol N 2015; 78/111(2): 196-199

Category: Short Communication

Overview

Sleep disturbances are one of the most common non-motor symptoms in patient with Parkinson’s disease (PD) with community‑based studies reporting prevalence data of 60%. Differences in symptoms between men and women have been reported.

Aim:

In the present study, we assessed whether there are gender differences in clinical presentation of PD and prevalence of sleep disturbances in individuals diagnosed in the Slovak Republic.Material and method:

Questionnaires were distributed to participating neurologists and patients in outpatient practices across the Slovak Republic. Sociodemographic variables – gender, age, age at onset, disease severity according to Hoehn and Yahr stage, phenotype of the dominating symptom of Parkinson’s disease and type of medication – were collected. The Slovak language version of the PDSS was used in a questionnaire to test sleep disturbances.Results:

Data from 1,067 outpatients with PD were collected. Comparative analyses showed males and females not to be significantly different on the majority of the demographic and medical characteristics collected. Males had a slightly higher proportion of individuals with Hoehn and Yahr score 4 and, among those taking levodopa medication as monotherapy, males took significantly higher levodopa dose than females (p < 0.01). A significant difference in the distribution of PDSS subscores between males and females was observed on item 7 (distressing hallucinations at night) – score for males 8.22, for females 8.48, p < 0.05. Similar result was observed on item 8 (getting up to pass urine) – score for males 5.90, for females 6.53, p < 0.01.Key words:

Parkinson’s disease – gender differences – sleepIntroduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by movement dysfunction and non‑motor impairment. More men than women are diagnosed with PD by a ratio of approximately 2 : 1 [1]. Differences in symptoms between men and women have been reported – rigidity and rapid eye movement behavior disorder are more often present in men, dyskinesias and depression in women [2]. Studies have reported developmental and functional differences of the nigrostriatal system associated with sex hormones between males and females [3]. Others suggest that estrogen may influence pathogenesis of PD and help to explain reduced incidence of PD in women [4].

Sleep disturbances are one of the most common non‑motor symptoms in patient with PD in community‑based studies reporting prevalence of 60% in PD patients, compared with 33% in healthy age ‑ and sex ‑ matched controls [5]. Gender differences have been found in the presence of rapid eye movements behavior disorder [6,7]. Sleep can by evaluated by history, scales and neurophysiological methods. Six scales were found to meet criteria for recommendation or suggestion [8]. One of them – The Parkinson’s Disease Sleep Scale (PDSS) – is intended to screen for the presence of many different sleep disorders found in Parkinson’s disease patients and provide a general impression of their severity [9]. In the present study, we assessed gender differences in clinical presentation of sleep disturbances, as evaluated by PDSS in individuals diagnosed with PD in the Slovak Republic.

Methods

Questionnaires were distributed to participating neurologists in outpatient practices across the Slovak Republic. Physicians and patients completed the questionnaire as part of the local documentation for routine clinical practice. After this time period, questionnaires were collected by the study coordinator.

Subjects

To be included, the patient had to be diag-nosed with PD as defined by the United Kingdom Brain Bank Criteria [10] and be able to give an informed consent and complete the research questionnaire. Socio ‑ demographic variables in the questionnaire – gender, age, age at onset, disease severity according to Hoehn and Yahr (H & Y) [11], phenotype of the dominating PD symptom and medication – were collected by the physicians using data from the patient interview and documentation.

Sleep disturbances testing

To test the sleep disturbances, the questionnaire used the Slovak language version of the PDSS. Patients completed the PDSS based on the quality of their nocturnal sleep in the past week. The PDSS is composed of 15 items exploring eight aspects of sleep. Item 1 addresses the global quality of nocturnal sleep. Items 2–14 are related to the presence of nocturnal sleep disturbances and item 15 evaluates unexpected sleep during a day. The patient’s response to each item is marked on a visual analogue scale ranging from always (0) to never (10), except for item 1 (awful – 0, to excellent – 10). Total PDSS score ranges from 0 to 150, where a higher score represents better quality of nocturnal sleep. Translation of the original PDSS to the Slovak language was carried out by experts involved in research on PD.

Statistical analysis

To compare gender groups, we used t‑test (for continuous variables) and chi ‑ squared or Fisher’s exact test (for nominal variables). Significance level of 0.05 was used throughout the study.

Results

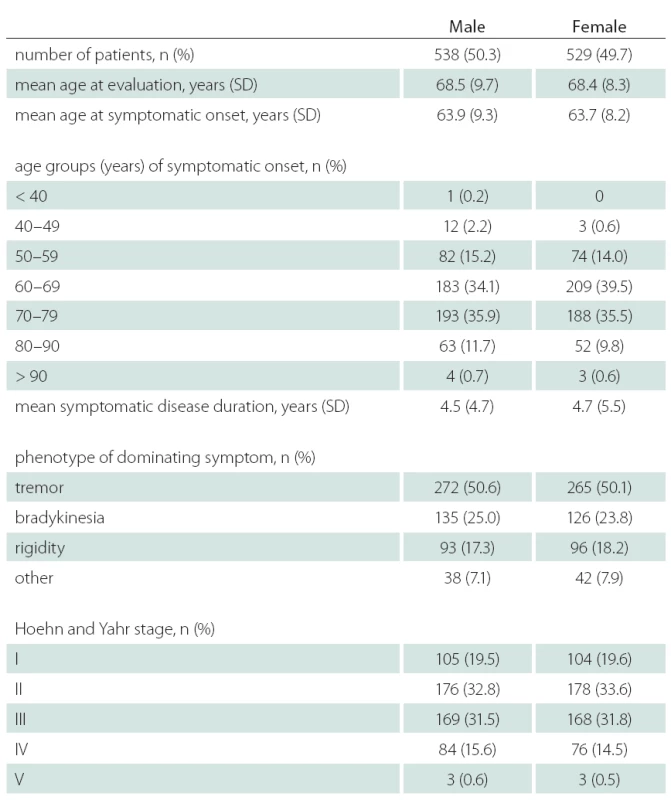

Data from 1,067 outpatients with PD were collected. Table 1 shows demographic, historical and clinical characteristics of the overall sample of patients by gender group. 50.3% of individuals in the sample were male, 49.7% were female. Comparative analyses showed males and females not to be significantly different on the majority of demographic and medical characteristics collected, p > 0.05. For both males and females, the mean age at the data collection was about 68 years, with proportional distribution of gender within the age subgroups (with the exception of the under 50 age group, where there were more males – 2.4% vs. 0.4% for males and females, respectively). The mean age at symptom onset was about 64 years. Disease duration was not significantly different between males and females (4.7 and 4.5 years, respectively). The majority of individuals in both gender groups reported tremor (about 50%) and bradykinesia (about 25%) as the dominant symptom of PD. The distribution of the dominating symptom type did not differ between males and females, p > 0.05. The majority of individuals were in the early to intermediate stage of PD (Hoehn and Yahr scale 3 or less) with proportional distribution between males and females. There was slightly higher proportion of males with Hoehn and Yahr scale of 4 (15.6% vs. 14.5% for males and females, respectively). The proportion of individuals taking specific subtypes of antiparkinsonian medication (levodopa only, an agonist only or a combined therapy) did not differ by sex. However, among those taking levodopa as monotherapy, males took significantly higher dose of levodopa than females (p < 0.01).

1. Demographic, historical and clinical characteristics in gender diff erence.

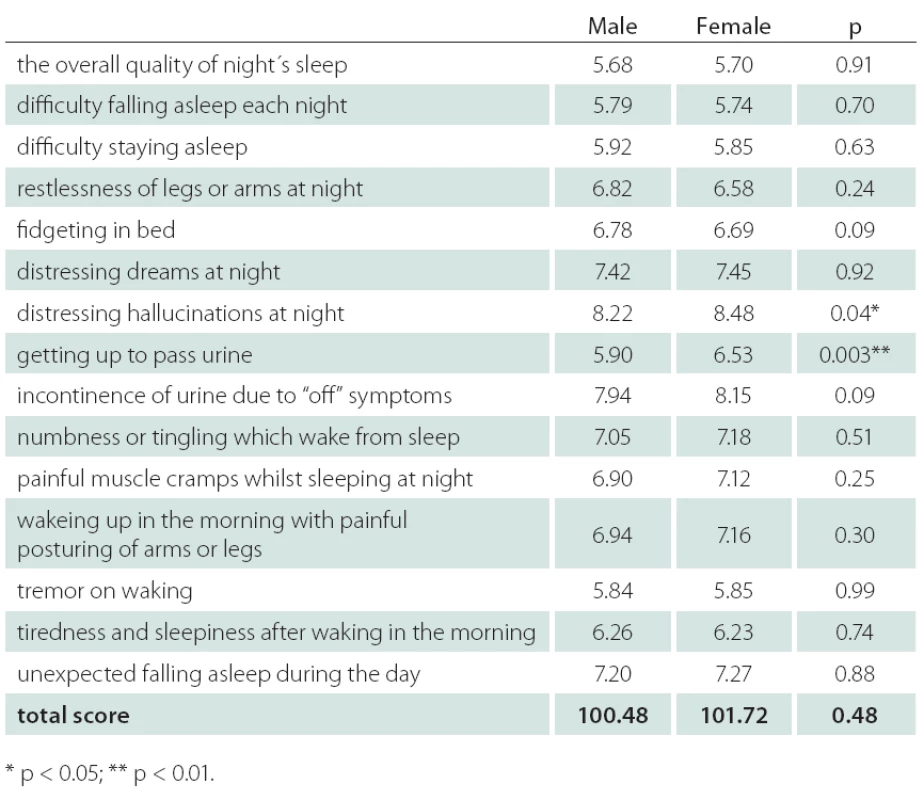

Table 2 shows the PDSS score components for males and females. Mean item score profiles are shown in Graph 1, for ease of comparison, similar data from the original study by Chaudhuri et al. [9] have been included. A significant difference in the distribution of PDSS subscores was observed between males and females on item 7 (distressing hallucinations at night) – score for males 8.22, for females 8.48, p < 0.05. Similar results were observed on item 8 (getting up to pass urine) – score for males 5.90, for females 6.53, p < 0.01.

2. PDSS in gender diff erence.

Graph 1. PDSS profi les of mean scores per item in Chaudhuri and colleagues, 2002 (grey line) and the current study (black line).

Discussion

In our study, we investigated 1,067 patients, where the equal male and female distribution is in contradiction to large clinical cohorts [12,13]. The reason for this difference is not clear and should be explained in future. Significant difference in life expectancy between genders in Slovakia might be one of the possible explanations.

In our study, there was no significant difference in the mean age at symptom onset and age at evaluation between males and females, consistent with other PD samples [14]. Additionally, the distribution of symptom phenotype, duration and disease severity according to the Hoehn and Yahr scale were similar between males and females. Thus, the disease progression rate from the onset of initial symptoms to baseline appears to be the same for both males and females. Similar disease progression rates between genders were reported also in other longitudinal studies of clinical samples [15,16].

Graph 1 shows the profile of mean PDSS scores obtained in our study and the study by Chaudhuri et al. [9], revealing a discrepancy in terms of direction on items 2 and 15 only. These discrepancies can be explained by different composition of the samples – patients in the present study had shorter disease duration and lower Hoehn and Yahr scores than patients in the original paper.

With respect to gender differences, significant difference between males and females was observed in the distribution of PDSS subscores on item 7 (distressing hallucinations at night) p < 0.05, and on item 8(getting up to pass urine) p < 0.01. Use of medication might be one of the possible explanations of the higher prevalence of night hallucinations among males. In a sample of nursing home patients with PD, men were more likely to receive antipsychotics, whereas women were more likely to receive antidepressants [17]. In the same sample, on the other hand, hallucinations were not more prevalent in either sex. Erroneous interpretation of vivid dreams as hallucinations might be another explanation. Ozekmekci at al. [7] noted that, of 35 PD patients with probable rapid eye movements behavior disorder (RBD), 77% were men. In the study of Yoritaka et al. [6] the presence of RBD in PD patients was associated with male gender with odds ratio of 2,469. In our study, statistically significantly more males got up to pass urine during night. The most common micturition abnormality in PD patients generally is related to detrusor hyperreflexia, while detrusor hypoactivity seems to be less prominent. In addition, paradoxical co ‑ contractions of the urethral sphincter muscle has been described as a correlate of off ‑ period voiding dysfunction in PD. Patients with mild detrusor hyperactivity may complain of nocturia with or without urgency during daytime, while urge incontinence is a feature of advanced PD only [18]; no gender differences in autonomic dysfunction causing micturition in PD patient have been reported. In the general population, nocturia is more prevalent in woman – in a recent Austrian study, mean nocturia score was 2.8 in men vs. 3.1 in women [19]; with 33%, nocturnal polyuria was the predominant cause of nocturia. The reason for male predominance in nocturia in our study remains unclear and needs to be evaluated in the future.

Several limitations of this study should be noted:

- the disease duration was relatively short (4.6 years) in this study;

- mainly PD patients in early and middle stages of the disease were enrolled, as indicated by the Hoehn and Yahr scale;

- to complete the questionnaire, we only chose PD subjects with sufficient cognitive ability, significantly narrowing the population in this study;

- current antiparkinsonian and concomitant medication was not investigated in detail, the same is true for comorbidity.

Therefore, larger studies need to be done, expanding the authors‘ work to a broader spectrum of factors with possible impact on sleep quality.

In conclusion, this is one of the largest reported clinic‑based study evaluating the relationship between the PD phenotype and gender and the first study evaluating the gender differences in sleep quality using the PDSS clinical scale. The majority of comparisons tended to highlight commonalities in the PD phenotype between males and females. The same is true for the majority of PDSS subscores, although significant difference in the distribution of PDSS subscores between males and females was observed on two of them – distressing hallucinations at night and getting up to pass urine were more frequent in male subjects . Further studies are needed to explain these differences.

We thank all patients and neurologists in outpatient practices for their cooperation. We are also grateful to Mr. Helbich for help with statistical analysis.

Accepted for review: 11. 8. 2014

Accepted for print: 20. 1. 2015

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

František Cibulčík, MD, PhD.

Department of Neurology

Slovak Medical University and University Hospital Bratislava

Ružinovská 6

826 06 Bratislava

Slovak Republic

e-mail: cibulcik@hotmail.com

Sources

1. Bordelon Y, Fahn S. Gender differences in movement disorders. In: Kaplan P (ed). Neurologic disease in women. New York: Demos 2006 : 349 – 354.

2. Miller IN, Cronin‑Golomb A. Gender differences in Parkinson’s disease: clinical characteristics and cognition. Mov Disord 2010; 25(16): 2695 – 2703. doi: 10.1002/ mds.23388.

3. Becker JB. Gender differences in dopaminergic function in striatum and nucleus accumbens. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1999; 64(4): 803 – 812.

4. Green PS, Simpkins JW. Neuroprotective effects of estrogens: potential mechanisms of action. Int J Dev Neurosci 2000; 18(4 – 5): 347 – 358.

5. Tandberg E, Larsen JP, Karlsen K. Excessive daytime sleepiness and sleep benefit in Parkinson’s disease: a community‑based study. Mov Disord 1999; 14(6): 922 – 927.

6. Yoritaka A, Ohizumi H, Tanaka S, Hattori N. Parkinson’s disease with and without REM sleep behaviour disorder: are there any clinical differences? Eur Neurol 2009; 61(3): 164 – 170. doi: 10.1159/ 000189269.

7. Ozekmekci S, Apaydin H, Kilic E. Clinical features of 35 patients with Parkinson’s disease displaying REM behavior disorder. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2005; 107(4): 306 – 309.

8. Högl B, Arnulf I, Comella C, Ferreira J, Iranzo A, Tilley B et al. Scales to assess sleep impairment in Parkinson’s disease: critique and recommendations. Mov Disord 2010; 25(16): 2704 – 2716. doi: 10.1002/ mds.23190.

9. Chaudhuri KR, Pal S, DiMarco A, Whately ‑ Smith C, Bridgman K, Mathew R et al. The Parkinson’s disease sleep scale: a new instrument for assesing sleep and nocturnal disability in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 73(6): 629 – 635.

10. Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico ‑ pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992; 55(3): 181 – 184.

11. Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 1967; 17(5): 427 – 442.

12. Ročný výkaz A (MZ SR) 18 – 01 o činnosti neurologických ambulancií za roky 2008 a 2009. Bratislava: Národné centrum zdravotníckych informácií 2009.

13. Parkinson study group. DATATOP: a multicenter controlled clinical trial in early Parkinson’s disease. Arch Neurol 1989; 46(10): 1052 – 1060.

14. Baba Y, Putzke JD, Whaley NR, Wszolek ZK, Uitti RJ. Gender and the Parkinson’s disease phenotype. J Neurol 2005; 252(10): 1201 – 1205.

15. Diamond SG, Markham CH, Hoehn MM, McDowell FH,Muenter MD. An examination of male ‑ female differences in progression and mortality of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 1990; 40(5): 763 – 766.

16. Marras C, Rochon P, Lang AE. Predicting motor decline and disability in Parkinson disease: a systematic review. Arch Neurol 2002; 59(11): 1724 – 1728.

17. Fernandez H, Lapane KL, Ott BR, Friedman JH. Gender differences in the frequency and treatment of behavior problems in Parkinson’s disease. SAGE Study Group. Systematic Assessment and Geriatric drug use via Epidemiology. Mov Disord 2000; 15(3): 490 – 496.

18. Poewe W. Dysautonomia and cognitive dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2007; 22 (Suppl 17): S374 – S378. doi: 10.1002/ mds.21681.

19. Klingler H Ch, Heidler H, Madersbacher H, Primus G. Nocturia: an Austrian study on the multifactorial etiology of this symptom. Neurourol Urodynam 2009; 28(5): 427 – 431. doi: 10.1002/ nau.20665.

Labels

Paediatric neurology Neurosurgery Neurology

Article was published inCzech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

2015 Issue 2-

All articles in this issue

- Progressive Dementia with Parkinsonism and Behavioral Changes – from the First Manifestations to the Neuropathological Confirmation (a Case Study)

- Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome (Ondine‘s Curse)

- A Neurological Complication of Hepatitis E – a Case Study

- Neurological Manifestation of Behçet’s Disease – a Case Report

- Succesfully Treated Depression in a Patient with Epilepsy – a Case Report

- Inflammatory Pseudotumor Imitating Intracranial Meningioma – a Case Report

- Neuromyelitis Optica

- Radiologic Assessment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis and its Clinical Correlation

- Aggressive Vertebral Hemangioma

- The Use of Antipsychotic Drugs in Patients with Dementia

- Intraluminal Shunt in Carotid Endarterectomies Increases the Risk of Ischemic Stroke

- Surgical Treatment of Lateral Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Using Percutaneous Interspinous Implant

- Surgical Approaches to Thalamic Tumors

- The Effect of Conservative Therapy on Diplopia in Patients with Paralytic Strabismus

- Functional Communication Questionnaire – Validation of the Original Czech Test

- Penile Vibratory Stimulation in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury

- A Registry of Mechanical Recanalization Procedures in Acute Stroke – Pilot Results from a Multicentre Registry

- Gender Differences in Clinical Presentation and Occurence of Sleep Disturbances in Patiens with Parkinson’s Disease – a Population‑ based Study

- Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Aggressive Vertebral Hemangioma

- Neuromyelitis Optica

- Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome (Ondine‘s Curse)

- Radiologic Assessment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis and its Clinical Correlation

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career